LEX 76741

Document 1

Page 1 of 14

s. 22(1)(a)(ii)

From:

s. 22(1)(a)(ii)

Sent:

Thursday, 23 November 2023 4:06 PM

To:

s. 22(1)(a)(ii)

Cc:

EPBC Offshore Renewables; s. 22(1)(a)(ii)

s. 22(1)(a)(ii)

Subject:

FW: Input request: review of NPRD final advice on Southern Offshore Declaration

Area [SEC=OFFICIAL:Sensitive]

Attachments:

s. 22(1)(a)(ii)

Advice: Proposed Southern Ocean

Region Declaration Area [SEC=OFFICIAL]

Hi s. 22(1)(a)(ii),

Thanks for the opportunity to again review NPRD’s draft brief for the NZID regarding advice on the proposed

SODA for renewable energy projects. Appreciate the consideration of our earlier feedback on the brief and I

note amendments have incorporated our comments to a large extent – s. 47C(1)

The attached Advice: Proposed SODA was submitted to NZID and NPRD’s offshore renewable team on the 31

Aug and replaces the earlier advice that you had included in the briefing pack attached to your 21 Nov email –

can you please include this version in the pack. If you could provide us a copy of the final brief that would be

appreciated.

Thanks again and happy to discuss our additional comments on the attached brief.

Thanks.

s. 22(1)(a)(ii)

s. 22(1)(a)(ii)

1

LEX 76741

Document 1

Page 2 of 14

s. 22(1)(a)(ii)

2

LEX 76741

Document 1

Page 3 of 14

s. 22(1)(a)(ii)

3

LEX 76741

Document 2

Page 4 of 14

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

MIGRATORY SPECIES SECTION

Advice: Southern Ocean Region Preliminary Declaration Area for Offshore Renewables

1.0

Recommendations

s. 47C(1)

2.0

Key Points

2.1

National and international legal obligations to protect marine species

1. Established under the

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) the

Australian Whale Sanctuary affords measures of protection for all 46 species of cetaceans in

Commonwealth waters. Twenty-nine cetacean species are found within the SOR declaration area.

This includes MNES:

• 4 Threatened and Migratory species including the Endangered pygmy blue whale (

Balaenoptera

musculus brevicauda), Endangered southern right whale (

Eubalaena australis), Vulnerable sei

whale (

Balaenoptera borealis) and Vulnerable fin whale (

Balaenoptera physalus).

• 10 additional Migratory cetacean species including the humpback whale (

Megaptera

novaeangliae).

2. The Australian Government has international obligations to protect migratory species within

Commonwealth waters under the

Convention for the Conservation of Migratory Species for Wild

Animals.

3. s. 47C(1)

4. Indigenous cultural linkages to cetaceans and other marine species should also be considered as a

priority.

1

LEX 76741

Document 2

Page 5 of 14

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

MIGRATORY SPECIES SECTION

3.0

Key considerations - environmental sensitivities

3.1

Biologically Important Areas

Biologically Important Areas (BIAs) are spatially, and temporally defined areas of the marine environment

used by protected marine species (Threatened and/or Migratory MNES, Cetaceans) for carrying out

critical life functions. BIAs are areas and times known or likely to be regularly or repeatedly used by

individuals or aggregations of a species, stock, or population for either reproduction, feeding, migration

or resting. BIAs are designated for some marine species protected under the Australian Government’s

regulatory framework and are used as a geospatial tool to inform decision-making and conservation

planning. Importantly marine species also undertake critical life functions outside of designated BIAs, and

not all species have BIAs. Impacts must still be considered whether within or external to currently

designated BIAs.

Of the 29 cetacean species known to occur within, or adjacent to the SOR declaration area this includes:

• a foraging BIA for the pygmy blue whale.

• a migration BIA for both the pygmy blue whale and the southern right whale.

• a reproduction BIA/HCTS for the southern right whale in waters adjacent to the SOR declaration

area boundary.

Not all species have designated BIAs within, or adjacent to, the proposed SOR declaration area due to a

lack of monitoring data:

• fin whales and sei whales are known to feed in the area.

• humpback whales are known to migrate through and forage in the area.

• pygmy right whales, sperm whales, killer whales and other cetaceans are likely to hunt and

forage in the area.

The SOR declaration area also occurs within the International Union for the Conservation of Nature

(IUCN) Southeast Australian and Tasmanian Shelf Waters Important Marine Mammal Area (IMMA), which

identifies this region as supporting a high diversity of cetaceans. The region supports valuable commercial

fisheries and large populations of marine birds and mammals and is regarded as biogeographically distinct

because of its unique cool-temperate flora and fauna (Gill et al 2015).

3.2 The Bonney Coast Upwelling System

The Bonney Coast Upwelling is part of the Great Southern Australian Coastal Upwelling System and

stretches from Portland, Victoria westwards to Kangaroo Island, South Australia. The Bonney Coast

Upwelling is the largest and most predictable area of surface upwelling in the Great Southern Australian

Coastal Upwelling System and is considered Australia’s most intense and productive upwelling (Butler et.

al. 2002) providing a feeding resource for protected cetaceans, migratory shorebird and seabirds. The

Bonney Coast Upwelling is a regionally significant upwelling that brings cold nutrient rich water to the sea

surface supporting high species diversity. Such upwellings typically support high densities of marine fauna

and high cetacean diversity, and the area probably aggregates cetacean prey species to a degree not

found around most of the Australian continent (Gill et al 2015). The proposed SOR declaration area

overlaps the regionally significant Bonney Coast Upwelling KEF and adjacent waters.

2

LEX 76741

Document 2

Page 6 of 14

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

MIGRATORY SPECIES SECTION

The Bonney Coast Upwelling is a known critical foraging area (BIA) for the pygmy blue whale (DCCEEW,

2015) supported by both acoustic and observational survey data. Worldwide, only 12 feeding sites for

blue whales have been identified, two of which are in Australian waters - the Bonney Coast Upwelling and

the Perth Canyon Upwelling (refer Assessment of the Conservation Values of the Bonney Upwelling). The

KEF does not cover the entire oceanographic upwelling feature that is highly variable spatially and

temporally and reliant on seasonal spring-summer winds. Therefore, the KEF does not accurately capture

all foraging areas used by the pygmy blue whale, as high primary and secondary productivity areas extend

beyond the designated KEF boundary limits and are driven by changing environmental conditions.

The currently designated boundary of the KEF and the pygmy blue whale foraging BIA do not align

because the whales are not responding to the location of the upwelling, rather the prey generated by the

upwelling system. Pygmy blue whale sighting data indicates that waters surrounding the KEF out to the

1000m depth contour and east to Cape Otway are also part of the Bonney Coast Upwelling and utilised as

important foraging areas (Gill et al. 2013, McCauley et al. 2018, Blue Whale Study).

3.3

Cetaceans

Cetaceans are highly mobile marine animals and are known to have spatial and temporal variability, both

intra- and inter-annually in the consistent use of specific areas across and adjacent to the

SOR

declaration

area. This may be the result of normal seasonal migratory and movement patterns and breeding cycles as

well as changes in prey availability arising from short and long-term oceanographic influences such as

weather and climate change. In addition to the pygmy blue whale, other cetacean species (29 in total)

including sei whales, fin whales, humpback whales, sperm whales, pygmy right whales and dolphins have

also been recorded feeding in the Bonney Coast Upwelling (Gill et al 2015).

It is expected that there will be cetaceans present at all times of the year within and adjacent to the SOR

declaration area. Given the temporal overlap between southern right whales and pygmy blue whales

there is no period of time during any year that one of these two Endangered MNES may not be present

within or near the SOR declaration area. For example:

• Southern right whales are present within the area of the Bonney Coast Upwelling and along the

Victorian coast annually between April and October.

• Pygmy blue whales are present in the Bonney Coast Upwelling annually between November and

May.

• Additionally, an estimated 45,000 humpback whales migrate annually along the east coast of

Australia between April and November, and have been observed foraging within the SOR

declaration area.

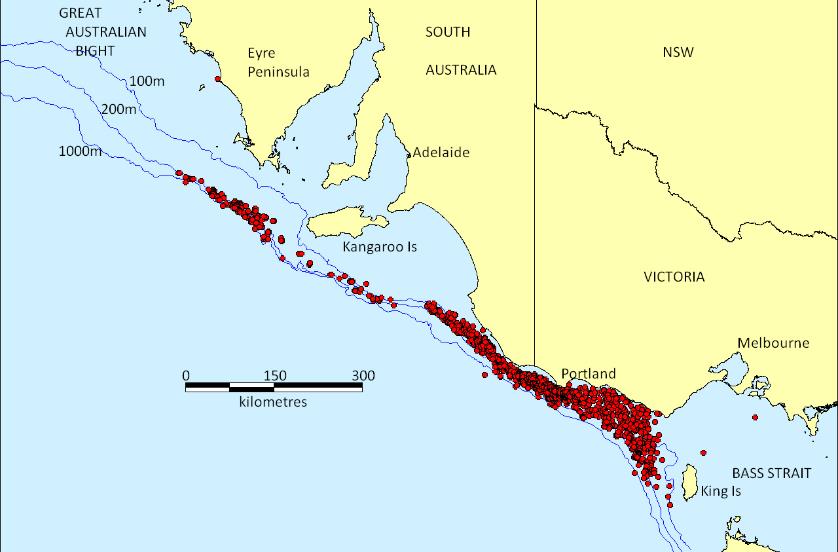

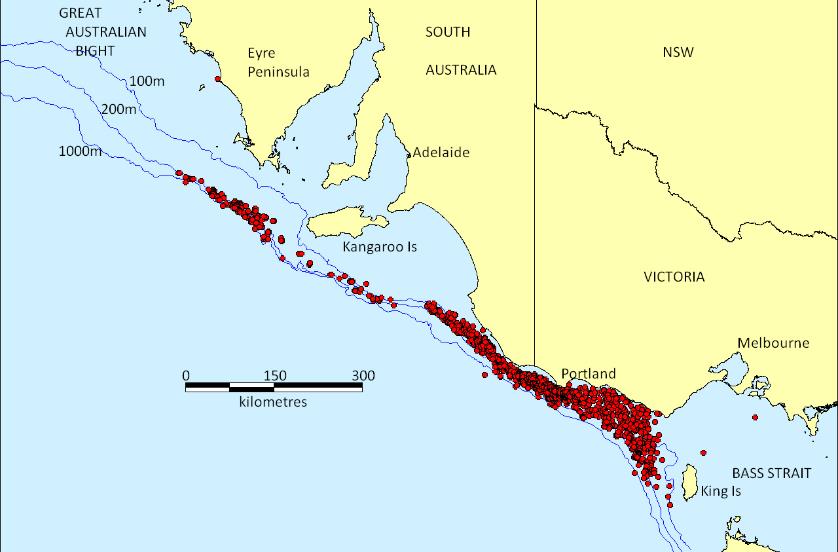

3.3.1 Pygmy blue whale (Endangered, Migratory, Cetacean)

The Bonney Upwelling in the SOR declaration area provides critical foraging habitat for pygmy blue

whales between around November to May annually. The distribution of approximately 1,600 blue whale

sightings gathered by the Blue Whale Study between 1998-2016 is shown in figure 1. Oceanographic

features and prey availability are dynamic processes that may change from year to year, affecting the

spatial and temporal use of the BIA by pygmy blue whales. Although the Bonney upwelling is considered

the largest and most predictable area of surface upwelling in the Great Southern Australian Coastal

Upwelling System, there is considerable seasonal variation in the location, timing, magnitude, and extent

of upwelling.

3

LEX 76741

Document 2

Page 7 of 14

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

MIGRATORY SPECIES SECTION

Given that a known foraging BIA for the pygmy blue whale exists across the proposed SOR

declaration

area, s. 47C(1)

In the Blue Whale Conservation Management Plan, a statutory recovery plan under the EPBC Act, ‘Action

Area A.2.3 requires that ‘Anthropogenic noise in Biologically Important Areas will be managed such that

any blue whale continues to utilise the area without injury, and is not displaced from a foraging area’.

Figure 1. Pygmy blue whale distribution1998-2016 (source: http://bluewhalestudy.org/the-bonney-upwelling)

3.3.2

Southern right whale (Eubalaena australis, Endangered, Migratory, Cetacean)

There are two genetically distinct populations of southern right whale within Australian waters, an east

Australian population, and a west Australian population (Carroll et al 2011). The eastern subpopulation

currently has only one established calving ground; Logans Beach at Warrnambool in south‐west Victoria

(Watson et al, 2021). The eastern population of southern right whales is of particular conservation

concern because it exhibits slow recovery from past whaling and abundance remains very low with an

estimated 268 whales (Stamation et al. 2021, Watson et al 2021).

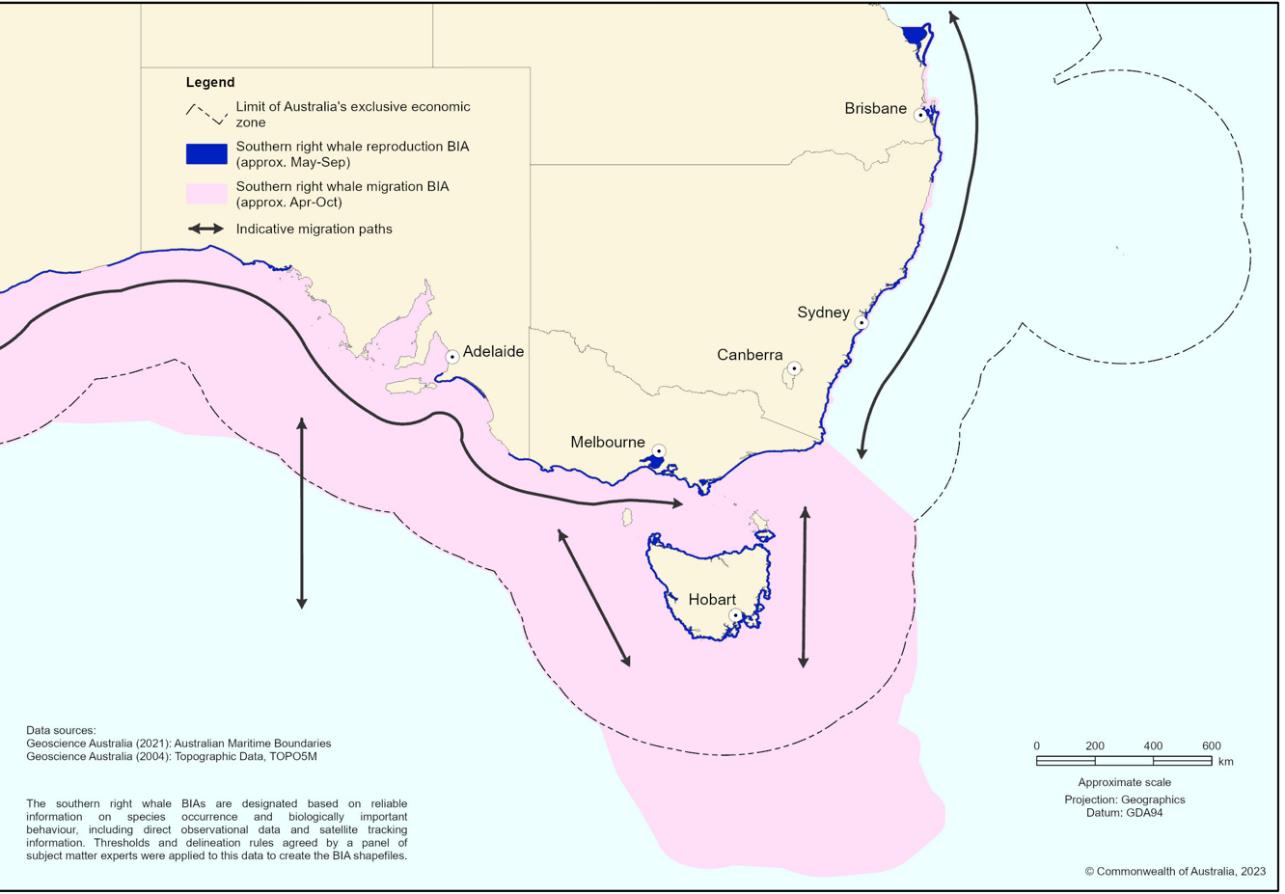

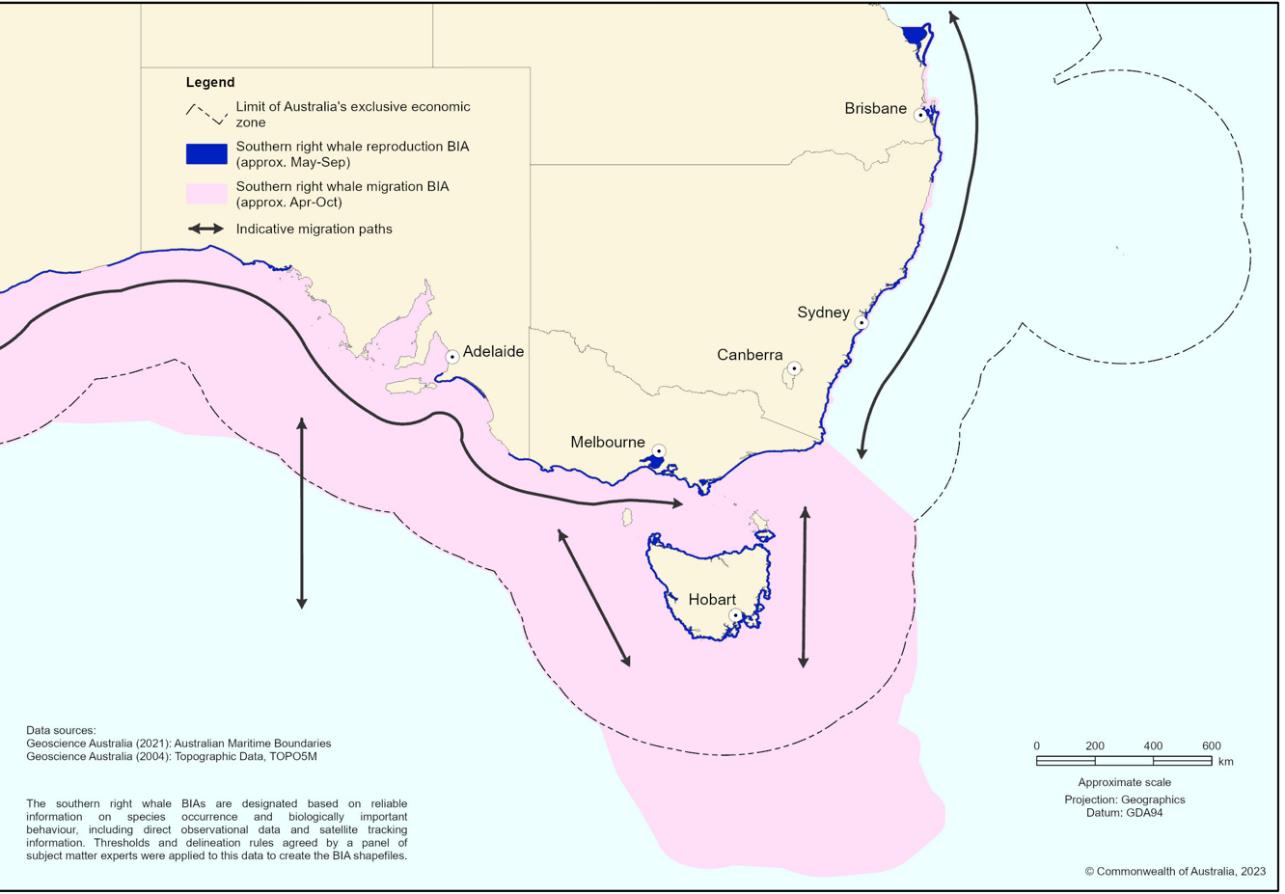

Southern right whales migrate annually between offshore foraging areas south of Australia and coastal

breeding areas. The Southern Ocean Declaration Area is located within the migration BIA for the southern

right whale and adjacent to the reproduction BIA (HCTS). The east Australian southern right whale

population breeds along the Victorian, Tasmanian, and New South Wales coastlines with the highest

densities of cow:calf pairs in Victoria recorded in western between Warrnambool and Portland (Watson

pers comm). Pregnant females and females with young calves likely migrate through the SOR declaration

area to and from these coastal breeding grounds. The first sightings of southern right whales in Victoria

each season generally occur around Portland and photoidentification data suggests that this area is an

important arrival point for southern right whales migrating westwards (Watson et al. 2021).

4

LEX 76741

Document 2

Page 8 of 14

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

MIGRATORY SPECIES SECTION

Connectivity with coastal habitat is critically important for migrating southern right whales. Females have

high fidelity to particular breeding sites, and it anthropogenic activities must not disconnect females from

regular coastal breeding habitat. s. 47C(1)

The potential for impacts from anthropogenic underwater noise is of particular concern in areas within or

close to HCTS for southern right whales i.e., the reproduction BIAs (DCCEEW 2022) where whales are

resident for long periods (e.g., weeks to months) of time, and pregnant and nursing females and calves

are present. In the draft new Recovery Plan for the Southern Right Whale a reproduction BIA (HCTS) is

designated along the Victorian coast (see figure 2). s. 47C(1)

The draft Southern Right Whale

Recovery Plan Action Area 5(1) states that ‘Actions within and adjacent to southern right whale BIAs and

Habitat Critical to Survival should demonstrate that they do not prevent any southern right whale from

utilising the area or cause injury (Temporary Threshold Shift and Permanent Threshold Shift) and/or

disturbance. Actions near BIAs should demonstrate that they do not prevent any southern right whale

from utilising the area without injury or disturbance’. Public comment on the new draft Southern Right

Whale Recovery Plan 2023 – 2033 closed on the 21 April 2023 and the range States will shortly be invited

to jointly make the Recovery Plan by the Minister for Environment and Water.

Figure 2: Southern right whale reproductive Biologically Important Area / Habitat Critical to Survival (source: Draft National

Recovery Plan for the Southern Right Whale (Eubalaena australis), Commonwealth of Australia 2022

5

LEX 76741

Document 2

Page 9 of 14

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

MIGRATORY SPECIES SECTION

3.3.3 Fin whale (Vulnerable, Migratory, Cetacean)

Sei whale (Vulnerable, Migratory, Cetacean)

Fin whales are generally thought to undertake long annual migrations from higher latitude summer

feeding grounds to lower latitude winter breeding grounds (Mackintosh 1965; Bannister 2008a; Aguilar

2009). Fin whales have been sighted in the proximity of the Bonney Upwelling, Victoria, along the

continental shelf in summer and autumn months (Gill 2002). Fin whales in the Bonney Upwelling are

sometimes seen in the vicinity of blue and sei whales. The sighting of a cow and calf in the Bonney

Upwelling in April 2000 and the stranding of two fin whale calves in South Australia suggest that this area

may be important to the species’ reproduction, perhaps as a provisioning area for cows with calves

(Morrice et al., 2004).

Sei whales are primarily found in deep water oceanic habitats and their distribution, abundance and

latitudinal migrations are largely determined by seasonal feeding and breeding cycles (Horwood 2009).

Sightings of sei whales within Australian waters includes areas such as the Bonney Upwelling off South

Australia (Miller et al., 2012), where opportunistic feeding has been observed between November and

May (Gill et al., 2015).

3.3.4

Humpback whales (

Megaptera novaeangliae; Migratory, Cetacean)

There are two humpback whale subpopulations in Australian waters: western Australian (stock D) and

eastern Australian (stock E1). The proposed SOR declaration area is within the eastern Australian

subpopulation’s core range. After feeding in Antarctic waters during the summer an estimated 45,000

humpback whales migrate slowly northwards along Australia’s eastern coastline from April to the winter

calving grounds of Queensland, returning in the southward migration by November each year.

The main migratory route of the eastern population diverges around Tasmania and the most recent

annual estimated population post whaling is 45,000 individuals. As advised by the Australian Antarctic

Division, these individuals migrate up the east coast of Australia to Hervey Bay in Queensland, along the

shoreline of Tas, Vic and NSW, primarily on the continental shelf. There is likely to be considerable

individual variability or fidelity to migratory route. At a population level, inter and intra-annual variability

related to climate and oceanographic influences are likely.

Humpback whales feed along the coastal migratory route, especially during the spring migration as they

return to the Southern Ocean feeding grounds. Supplemental feeding occurs annually along the east

coast of Australia, but it is currently unclear if feeding is opportunistic, in response to an abundance of

prey availability, or an essential aspect of their migratory ecology and annual energy budget. Feeding

humpback whales have been regularly observed off the coast of Portland (Watson pers. comm).

humpback whale feeding and migration behaviour overlaps with the SOR declaration area.

3.3.5

Other cetaceans

The Bonney upwelling supports a significant diversity of cetacean species, many with a paucity of

monitoring data available. Additional migratory cetacean species not discussed in this advice that are

known or likely to occur within the proposed SOR declaration area include as an example, the killer whale

(

Orcinus orca, Migratory, Cetacean), sperm whale (

Physeter macrocephalus, Migratory, Cetacean),

Antarctic minke whale (

Balaenoptera bonaerensis, Migratory, Cetacean), dusky dolphin (

Lagenorhynchus

obscurus, Migratory, Cetacean), pygmy right whale (

Caperea marginata, Migratory, Cetacean).

6

LEX 76741

Document 2

Page 10 of 14

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

MIGRATORY SPECIES SECTION

4.0

Potential impacts to cetaceans

s. 47C(1)

, and mitigation measures

demonstrate acceptable long-term environmental outcomes for protected species can be achieved

regionally. Individual declaration areas could host several offshore wind and other renewable energy

projects and marine species are already exposed to significant activities impacting their habitat including

offshore oil and gas operations, greenhouse gas storage, vessel traffic, fisheries, subsea communication

infrastructure, marine pollution, Australian Defence Force naval operations and climate variability.

Pre-construction, construction, operational and decommissioning activities for offshore renewable

energy infrastructure must be managed so that cetaceans engaged in biologically important behaviours

can continue without disturbance, displacement, or injury. s. 47C(1)

Habitat critical to the survival of a species is defined in statutory Recovery Plans. Under Part 13, section

270 of the EPBC Act, a Recovery Plan, must identify HCTS and the actions needed to protect those

habitats. The new draft National Recovery Plan for the Southern Right Whale has designated the

reproductive BIA as HCTS; and as previously noted, Action Area A2 in the Blue Whale Conservation

Management Plan is critical to managing the threat of anthropogenic underwater noise to the species. In

accordance with the EPBC Act, the Minister cannot make a decision that is inconsistent with a Recovery

Plan. s. 47C(1)

Cetaceans rely on sound for basic life functions

such as communication (including for mating), navigation, foraging, and predator avoidance.

s. 47C(1)

The Bonney upwelling is wind driven and wind is expected to change In line with a changing climate. The

response of the Bonney upwelling to climate change is uncertain, but the Bonney upwelling is clearly an

important feature as a prey resource which is particularly sensitive to climate change, and this must be

considered. s. 47C(1)

7

LEX 76741

Document 2

Page 11 of 14

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

MIGRATORY SPECIES SECTION

• s. 47C(1)

• Reductions in visibility can affect photosynthesis in algae, a critical component of the krill and

cetacean food chain, thereby further disrupting behaviours in marine animals.

• s. 47C(1)

• Increased risk of vessel interactions including injury and mortality due to increased traffic.

5.0 Migratory shorebirds

Migratory shorebirds are found primarily on the coast in all states of Australia. Migratory shorebirds

breed in northern hemisphere from May-June. Birds usually arrive to some non-breeding grounds in

August-October and leave northwards to breed between February-March/April. The exception to this is

double-banded plover which migrates to Australia from New Zealand during winter. Satellite-tracking and

geolocation studies indicate that they can migrate from south-east Australia to Yellow Sea in a single

flight but may have to stop if they encounter poor migration conditions. Time series data at many sites

across Australia have indicated a severe population decline in some species.

Important habitat for all 37 species that migrate to Australia can be found in the National Directory of

Important Migratory Shorebird Habitat.

Movement of migratory shorebirds across the proposed declaration area is possible. Large numbers of

migratory shorebirds are known to occur in north-west and north-east Tasmania and the Bass Strait

islands, particularly King and Flinders Islands. Migratory pathways, timing and flight elevation are all

uncertain factors and more research (i.e., tracking) is needed. Some species arriving on the east coast of

Australia continue on to New Zealand crossing the Tasman Sea.

s. 47C(1)

6.0 Seabirds

Bass Strait has a high seabird diversity with large breeding colonies occurring on offshore islands. The

Bass Strait Islands, including King Is and the Furneaux Group have large breeding colonies of short-tailed

shearwaters (Listed Migratory), fairy prion, common diving-petrel, white-faced storm-petrel, little

penguin, Australasian gannet, gulls, terns and cormorants (Brothers et al. 2001). Australian fairy tern

(Vulnerable, see Recovery Plan) and little tern (Migratory) are likely to move through the proposed

declaration area along with many other species.

In relation to the proposed declaration areas, offshore islands near Portland (Lawrence Rocks, Lady Julia

Percy Island and Griffith Island at Port Fairy) are important seabird breeding islands. Individuals from

other island groups will enter the proposed declaration areas on migration and/or foraging trips. For

example, short-tailed shearwaters generally return to their burrows every night but some feed 150 – 200

8

LEX 76741

Document 2

Page 12 of 14

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

MIGRATORY SPECIES SECTION

km from colonies (Brothers et al. 2001). Migratory pathways, timing and flight elevation are all uncertain

factors, and more research is needed (i.e., tracking).

s. 47C(1)

Advice from the National Light Pollution Guidelines in relation to breeding seabirds should be considered

for relevant seabird species. s. 47C(1)

7.0

Other marine species

There are three species of marine turtles that are likely/may occur in the proposed declaration area

including the leatherback turtle (Endangered, Migratory), the loggerhead turtle (Endangered, Migratory),

and the green turtle (Vulnerable).

9

LEX 76741

Document 2

Page 13 of 14

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

MIGRATORY SPECIES SECTION

8.0

References

1. Aguilar, A. & C. Lockyer (1987). Growth, physical maturity, and mortality of fin whales (Balaenoptera

physalus) inhabiting the temperate waters of the northeast Atlantic. Canadian Journal of Zoology.

65:253-264

2. Andrews-Goff, V., Bestley, S., Gales, N.J., Laverick, S.M., Paton, D., Polanowski, A.M., Schmitt, N.T. &

Double, M.C. (2018) Humpback whale migrations to Antarctic summer foraging grounds through the

southwest Pacific Ocean. Sci Rep 8, 12333 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30748-4

3. Brothers, N., Pemberton, D., Pryor, H., and Halley, V. (2001) Tasmania’s Offshore Islands: Seabirds

and other natural features. Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, Tasmania.

4. Bannister JL (2008a) ‘Great Whales’ CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood

5. Blue Whale Study. http://bluewhalestudy.org/the-bonney-upwelling/

6. Burnell S. (2001) Aspects of the reproductive biology, movements and site fidelity of right whales off

Australia. Journal of Cetacean Research Management: 89-102. url:

https://journal.iwc.int/index.php/jcrm/article/view/272

7. Burnell, S.R. (1997) An incidental flight network for the photo-identification of southern right whales

off southeastern Australia. A summary of research activities undertaken in the 1995 and 1996

seasons. Report by Eubalaena Pty. Ltd to BHP Petroleum Pty. Ltd. and Esso Australia Ltd. 30pp.

8. Butler, A., F. Althaus, D. Furlani, and K. Ridgway. 2002. Assessment of the conservation values of the

Bonney Upwelling. A component of the Commonwealth Marine Conservation Assessment Program

2002–2004. CSIRO report to Environment Australia. CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research,

Hobart, Tasmania, Australia

9. DCCEEW 2015 Conservation Management Plan for the Blue Whale, Commonwealth of Australia.

10. DCCEEW 2015 Conservation Advice

Balaenoptera physalus (fin whale), Commonwealth of Australia

2015

11. DCCEEW 2015 Conservation Advice

Balaenoptera borealis (sei whale), Commonwealth of Australia

2015

12. DCCEEW 2017 National Strategy for Reducing Vessel Strike on Cetaceans and other Megafauna,

Commonwealth of Australia 2017

13. DCCEEW 2022 Draft National Recovery Plan for the Southern Right Whale (

Eubalaena australis),

Commonwealth of Australia 2023

14. DCCEEW 2021 Guidance on key terms within the Blue Whale Conservation Management Plan -

DCCEEW

15. EPBC Act Policy Statement 2.1 Interaction between offshore seismic exploration and whales

16. Erbe, Christine & Dunlop, Rebecca & Dolman, Sarah. (2018). Effects of Noise on Marine Mammals.

10.1007/978-1-4939-8574-6_10.

17. Ellison, W. T., Southall, B. L., Clark, C. W. and Frankel, A. S., (2011) A New Context-Based Approach to

Assess Marine Mammal Behavioral Responses to Anthropogenic Sounds. Conservation Biology

26(1):21 – 8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01803.x

18. Gill PC, Pirzl R, Morrice MG, Lawton K (2015) Cetacean diversity of the continental shelf and slope off

southern Australia. The Journal of Wildlife Management

19. Horwood, J.W. (1987). Population Biology, ecology and management. The Sei Whale. Croom Helm,

New York

20. Mackintosh, N.A. (1965). The stocks of whales. London: Fishing News (Books) Ltd

21. McCauley RD, Gavrilov AN, Jolliffe CD, Ward R & Gill PC (2018) Pygmy Blue and Antarctic Blue Whale

Presence, Distribution and Population Parameters in Southern Australia Based on Passive Acoustics.

Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 157-158, 154-168. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2018.09.006

10

LEX 76741

Document 2

Page 14 of 14

DEPARTMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER

MIGRATORY SPECIES SECTION

22. Miller BS, Kelly N, Double MC, Childerhouse SJ, Laverick S, Gales N (2012) Cruise report on SORP

2012 blue whale voyages: development of acoustic methods. Paper SC/64/SH1 1 presented to the

IWC Scientific Committee.

23. Morrice, M.G, P.C. Gill, J. Hughes & A.H. Levings (2004). Summary of aerial surveys conducted for the

Santos Ltd EPP32 seismic survey, 2-13 December 2003. Report # WEG-SP 02/2004, Whale Ecology

Group-Southern Ocean, Deakin University. unpublished.

24. Noad, MJ, Kniest, E, Dunlop, RA. (2019) Boom to bust? Implications for the continued rapid growth of

the eastern Australian humpback whale population despite recovery. Popul Ecol.; 61: 198– 209.

https://doi.org/10.1002/1438-390X.1014

25. Pirotta, V, Owen, K, Donnelly, D, Brasier, MJ, & Harcourt, R. (2021) First evidence of bubble-net

feeding and the formation of ‘super-groups’ by the east Australian population of humpback whales

during their southward migration. Aquatic Conserv: Mar Freshw Ecosyst. 2021; 31: 2412– 2419.

https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.3621

26. Stamation K, Watson M, Moloney P, Charlton C & Bannister J (2020) Population Estimate and Rate of

Increase of Southern Right Whales

Eubalaena Australis in Southeastern Australia. Endangered

Species Research 41, 373-383. doi: https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01031.

27. Watson, M, Stamation, K, Charlton, C & Bannister, J. (2021) Calving intervals, long-range movements

and site fidelity of southern right whales (

Eubalaena australis) in south-eastern Australia. Journal of

Cetacean Research and Management, 22.

11