Contents

Document 1

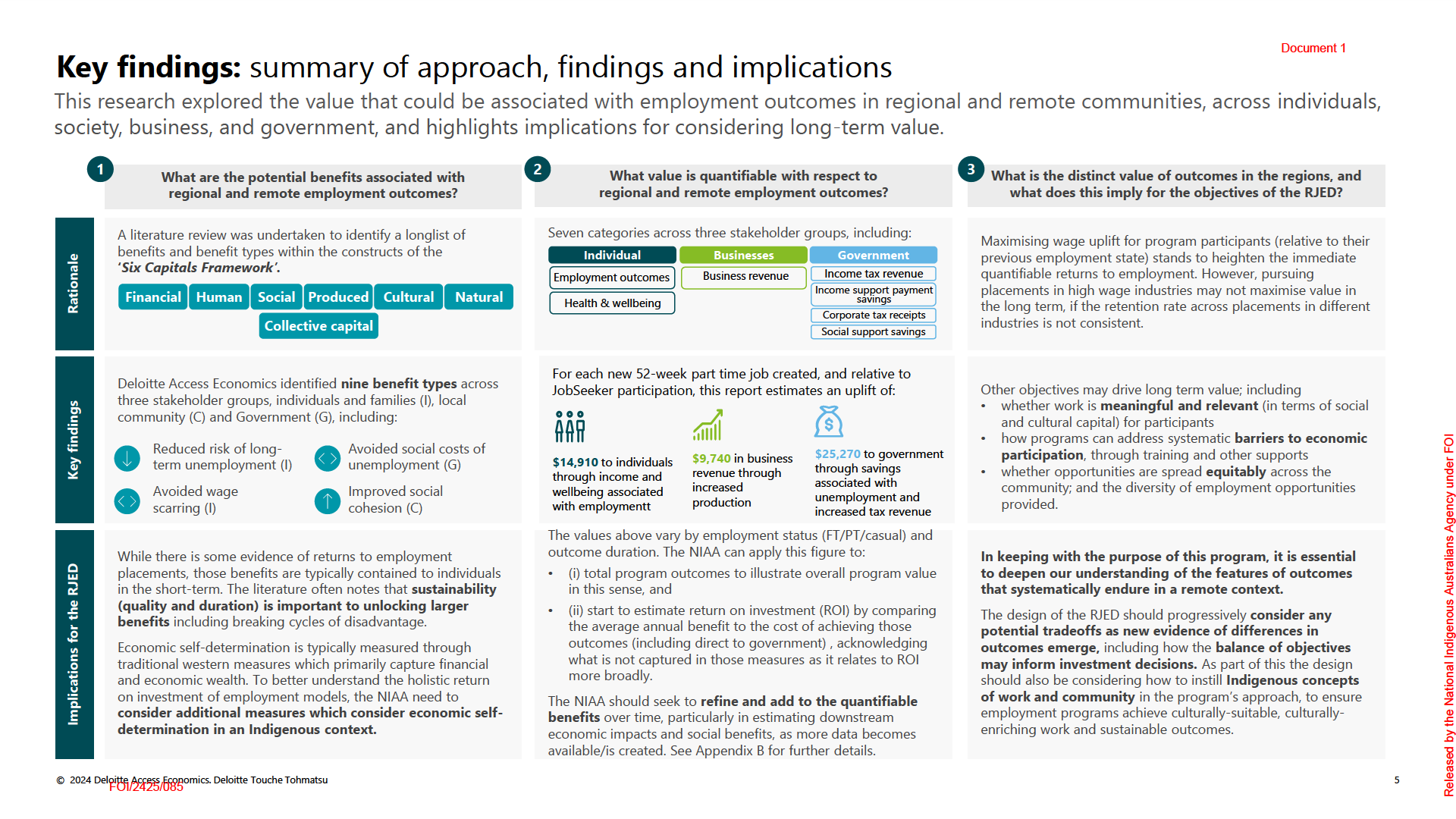

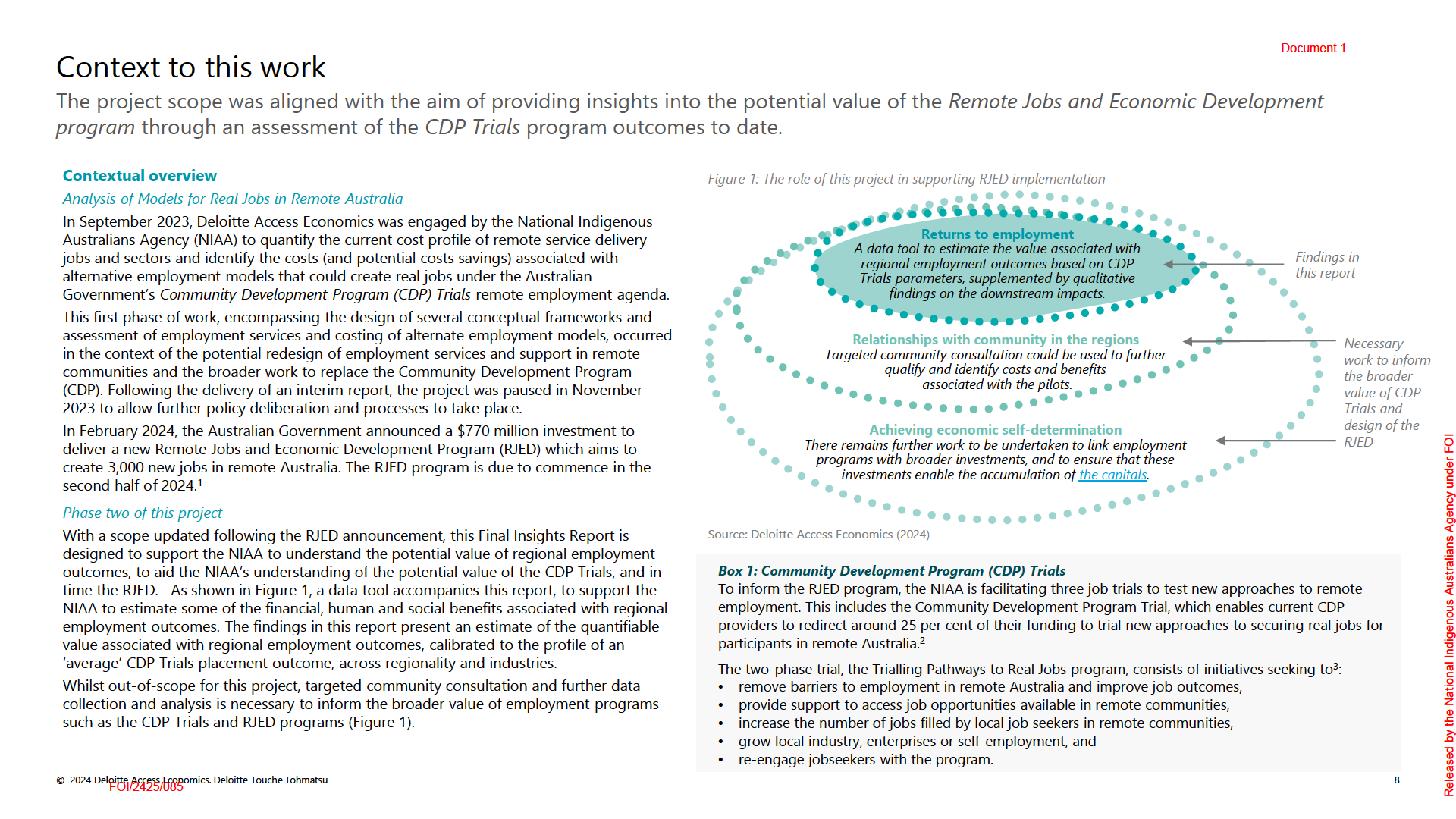

This Insights Report sets out the potential value associated with employment in remote communities. An accompanying data tool provides a

basis for the NIAA to further estimate the returns to employment outcomes across remote contexts, over time.

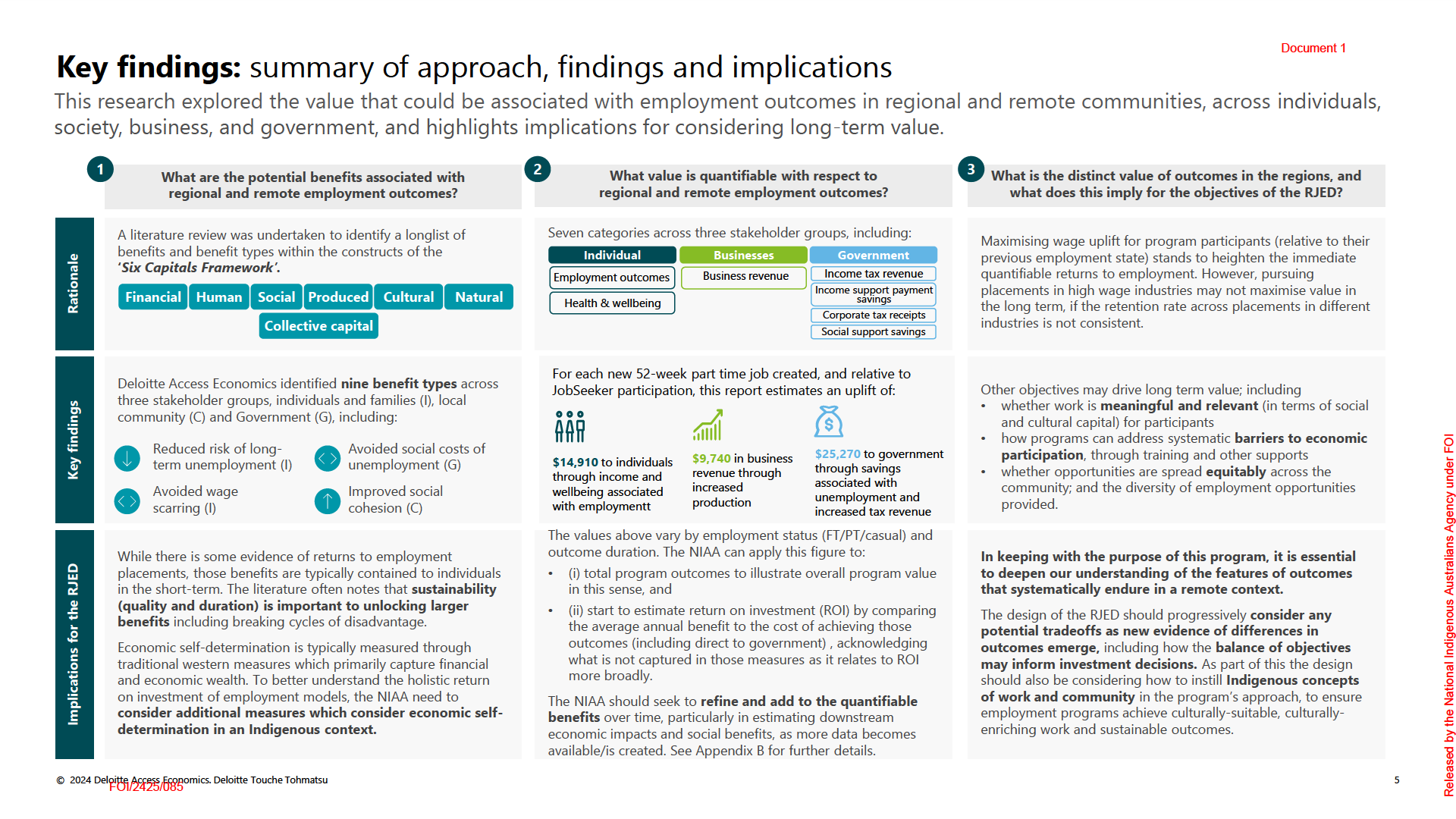

Reflections on the value of remote employment outcomes

3

3 | What is the distinct value of outcomes in the regions, and what

21

An overview of the key themes that emerge in this report – about how the

does this imply about maximising returns to the RJED?

value of remote employment* can be understood and measured, and the

An approach to assessing region-specific program outcomes, in lieu of

implications of these results for the design and impact of the RJED program.

region-specific program data, and a discussion of program levers to

maximising program returns.

Key Findings

4

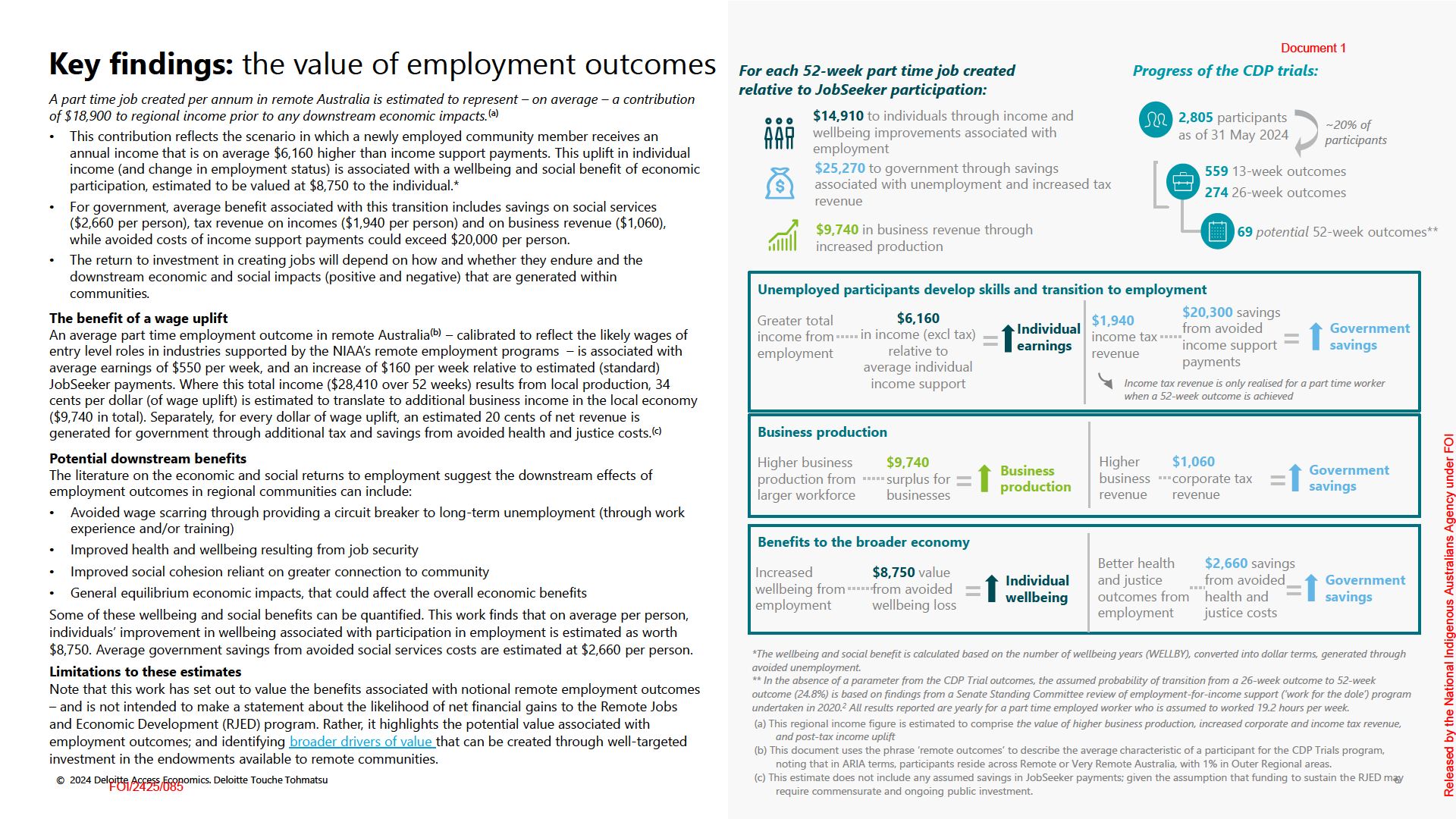

The high-level overview of quantitative benefits estimated as part of this work,

for a part time job created through a notional employment outcome.

Appendix A | Modelling assumptions and guide to using the data tool

26

Background and context

5

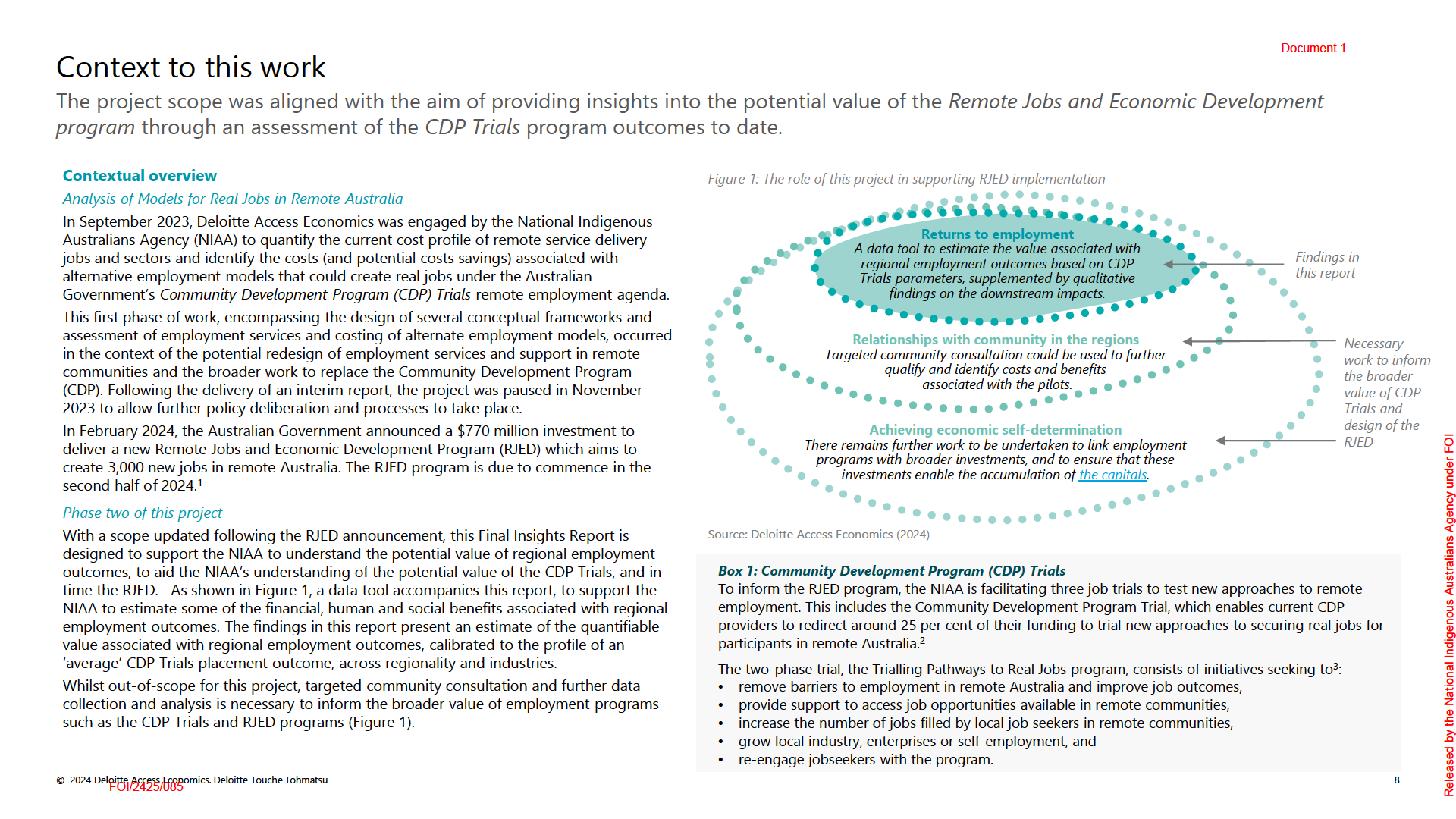

The context and motivation for the program and this work, including

Appendix B | Considerations for key assumptions and future

31

background to the initial phase of work, an overview of the three underpinning

refinements to estimating quantified benefits

analytical components, and guidance to interpret the results presented in this

document.

References

33

1 | What are the potential benefits associated with remote employment

10

outcomes?

Agency under FOI

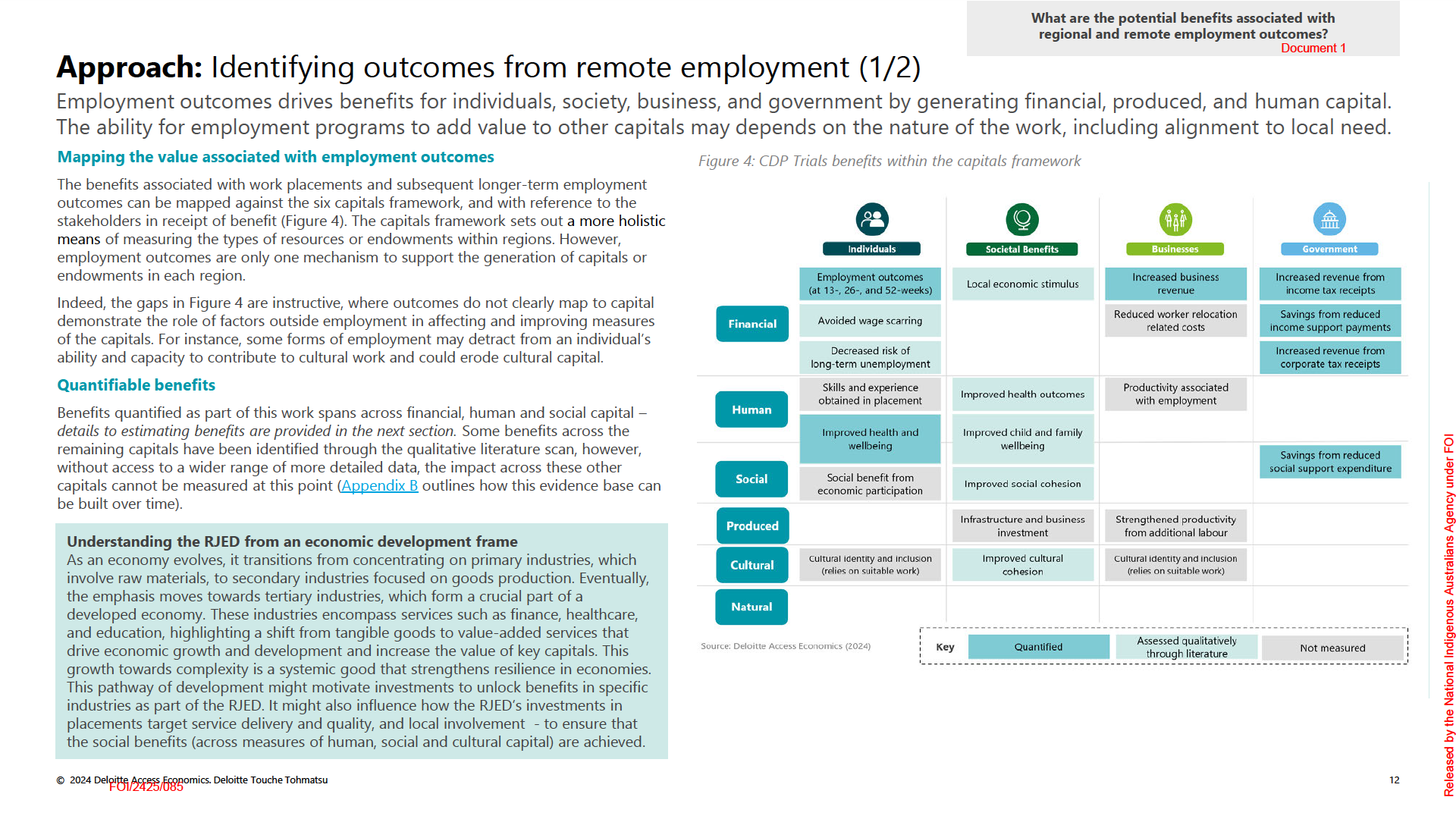

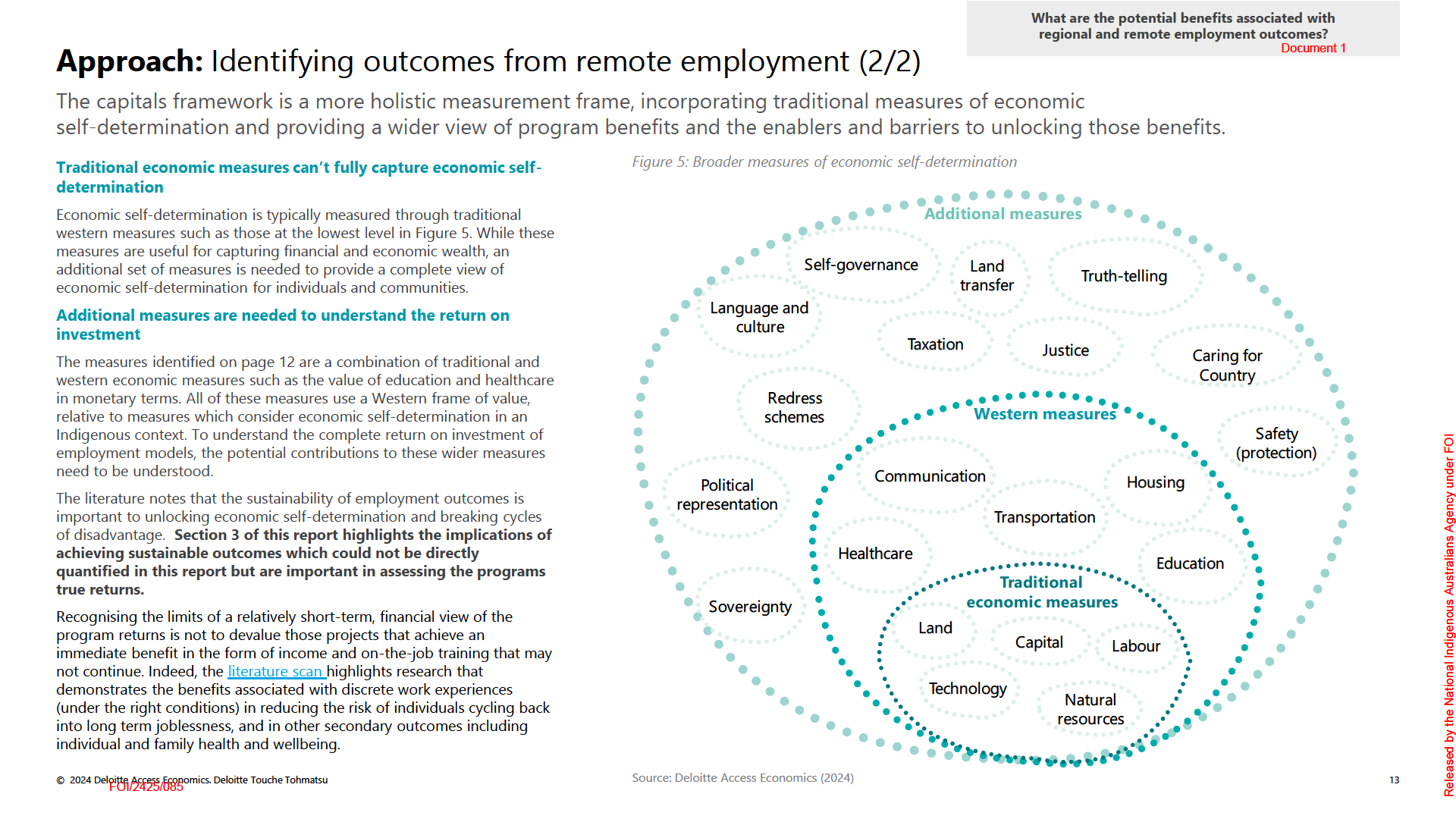

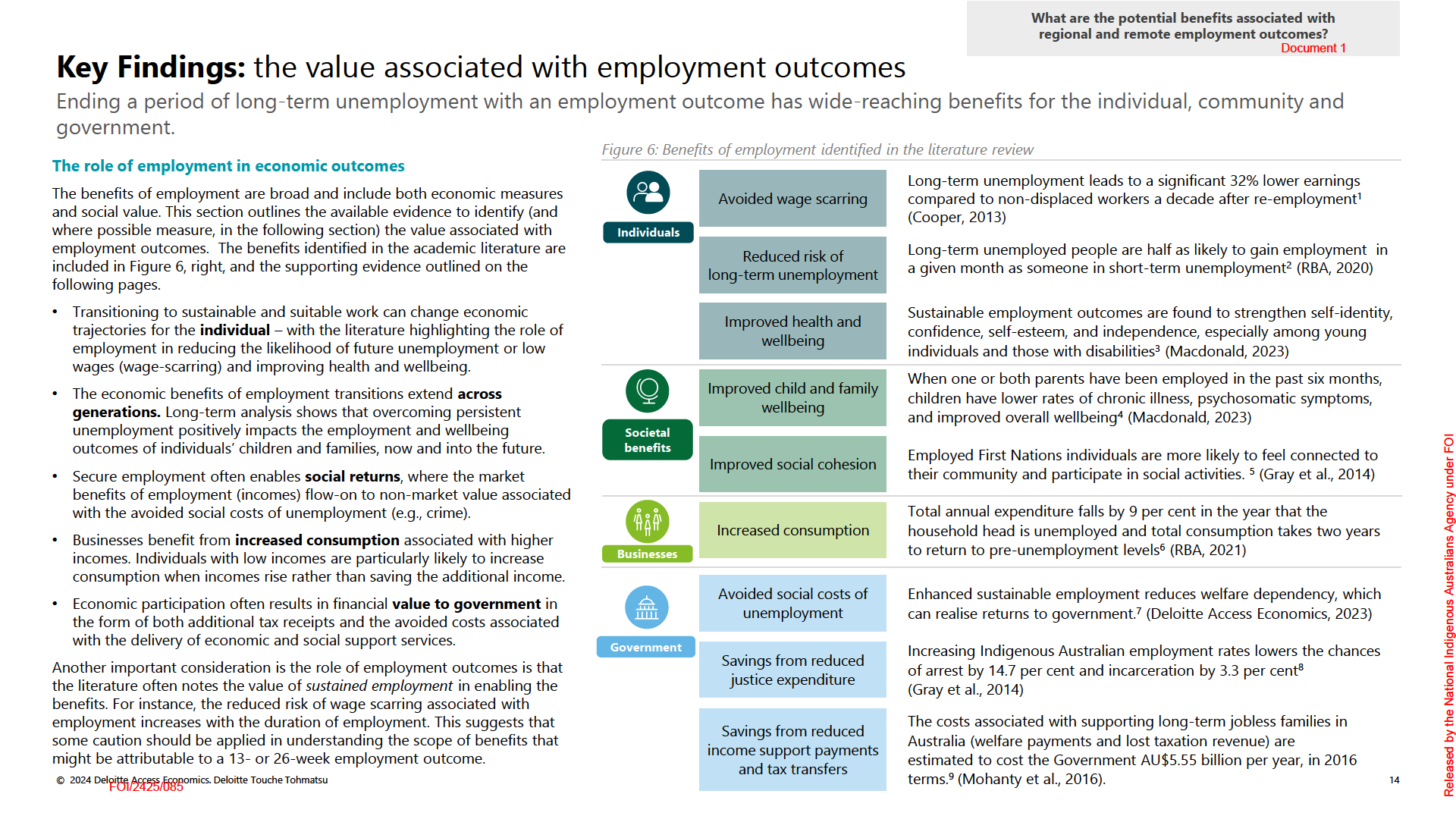

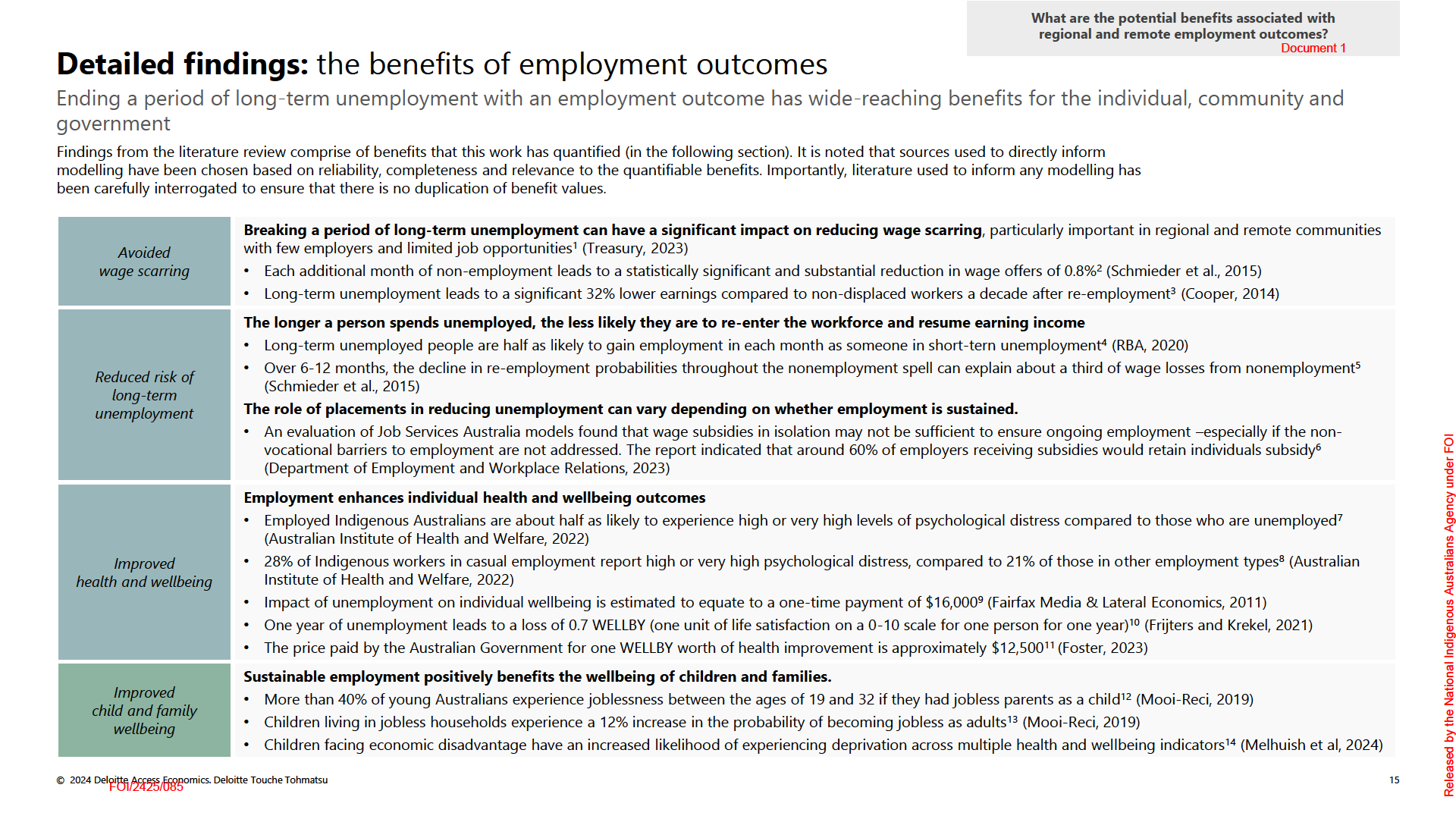

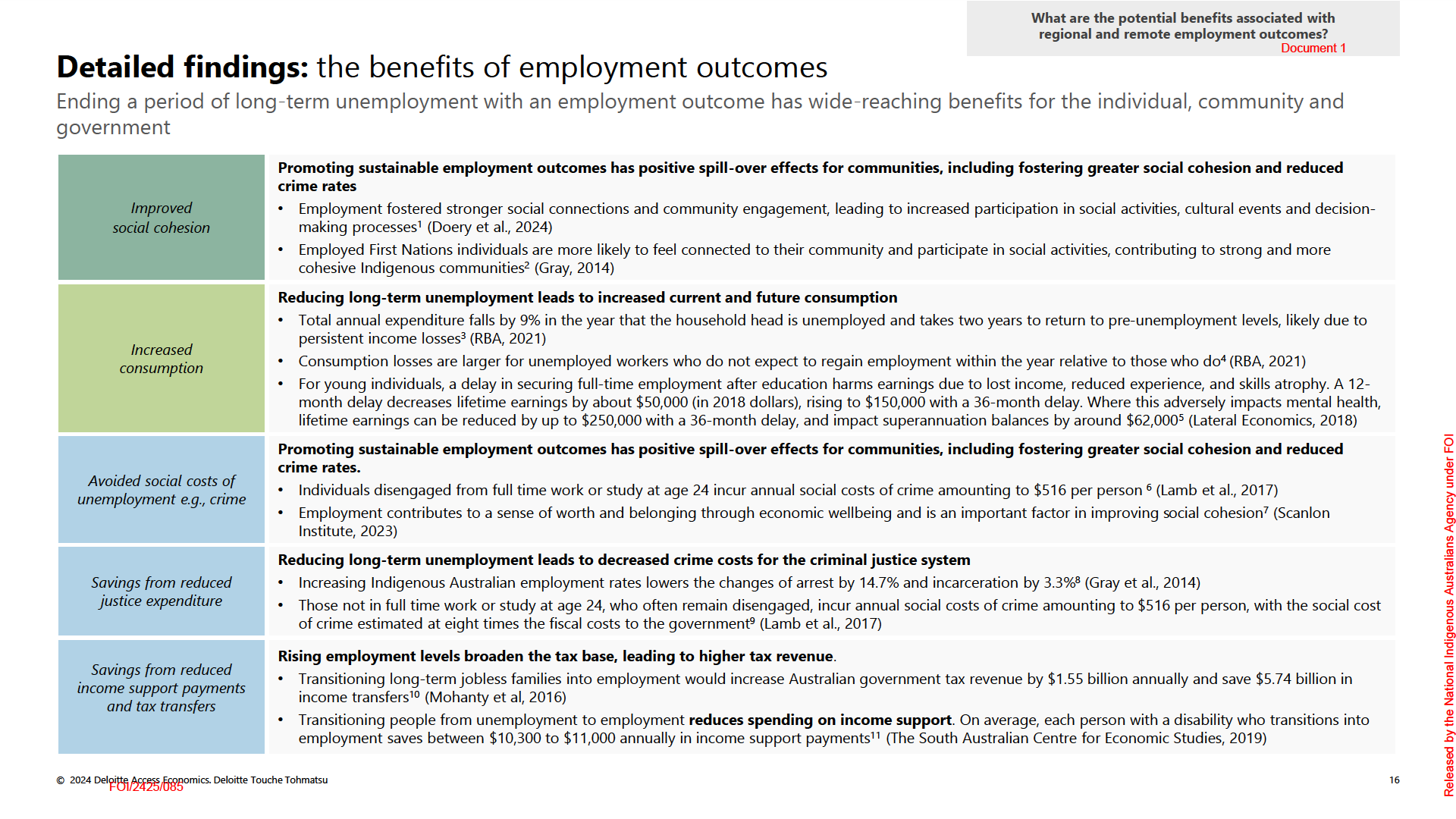

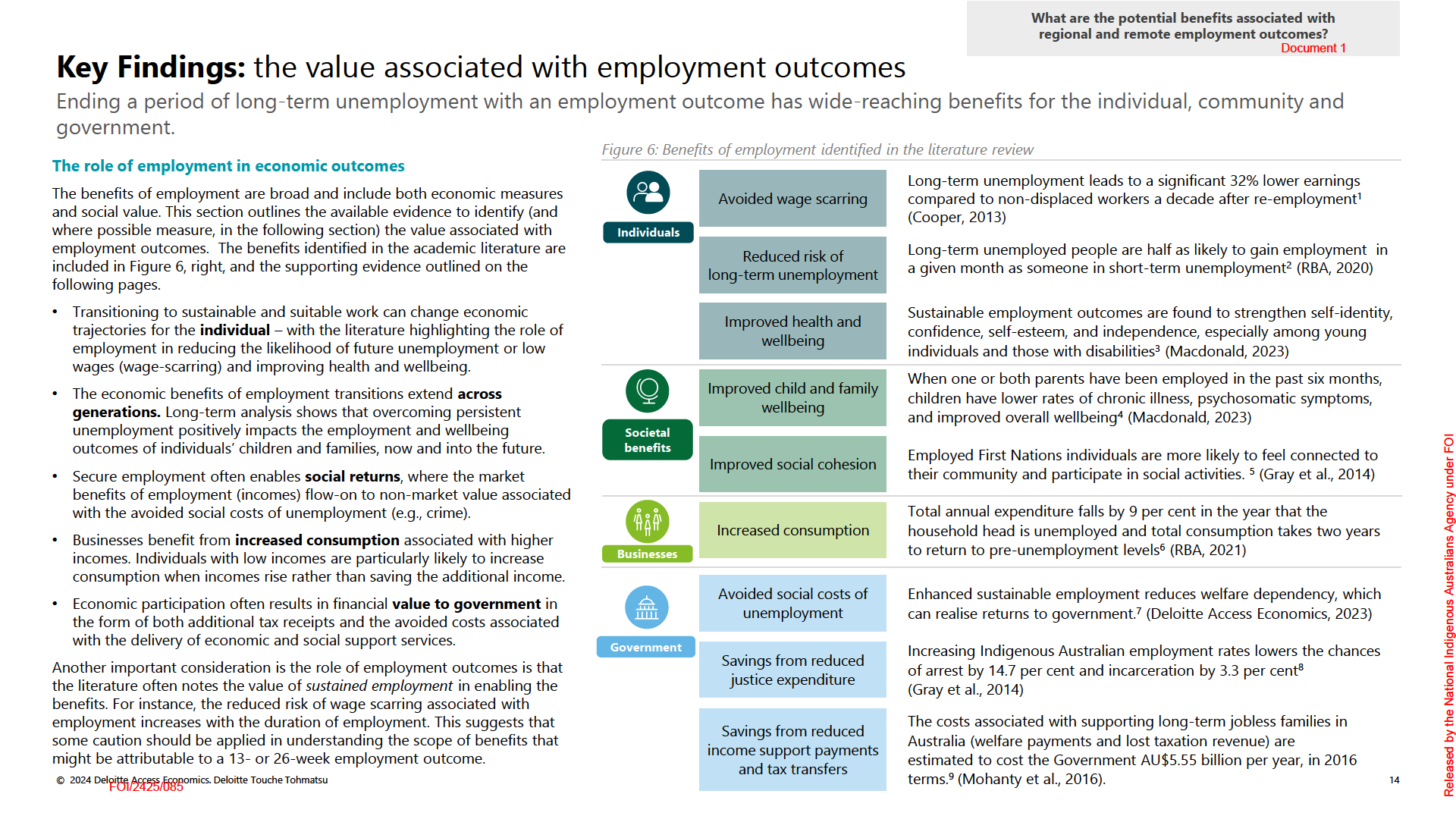

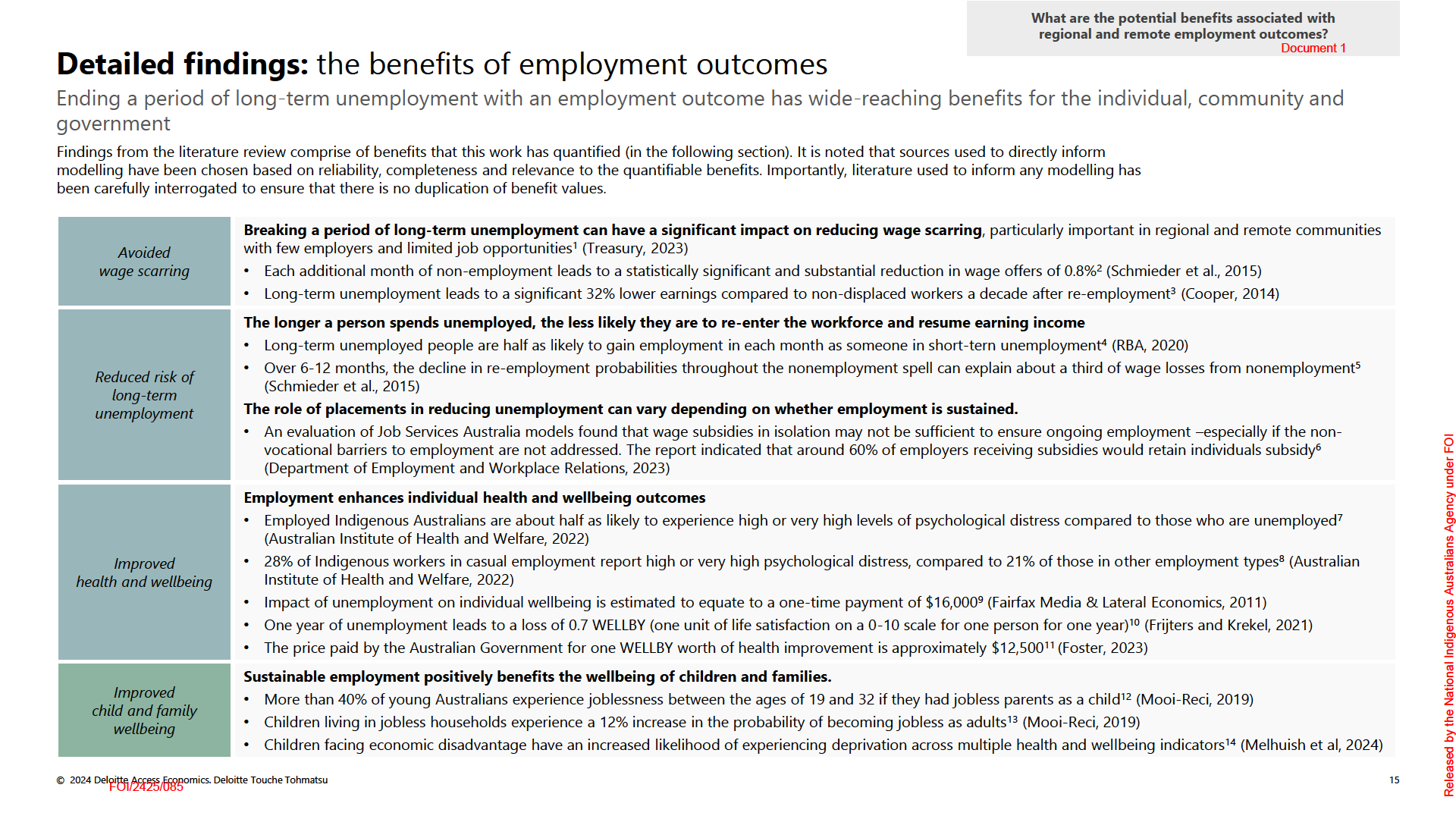

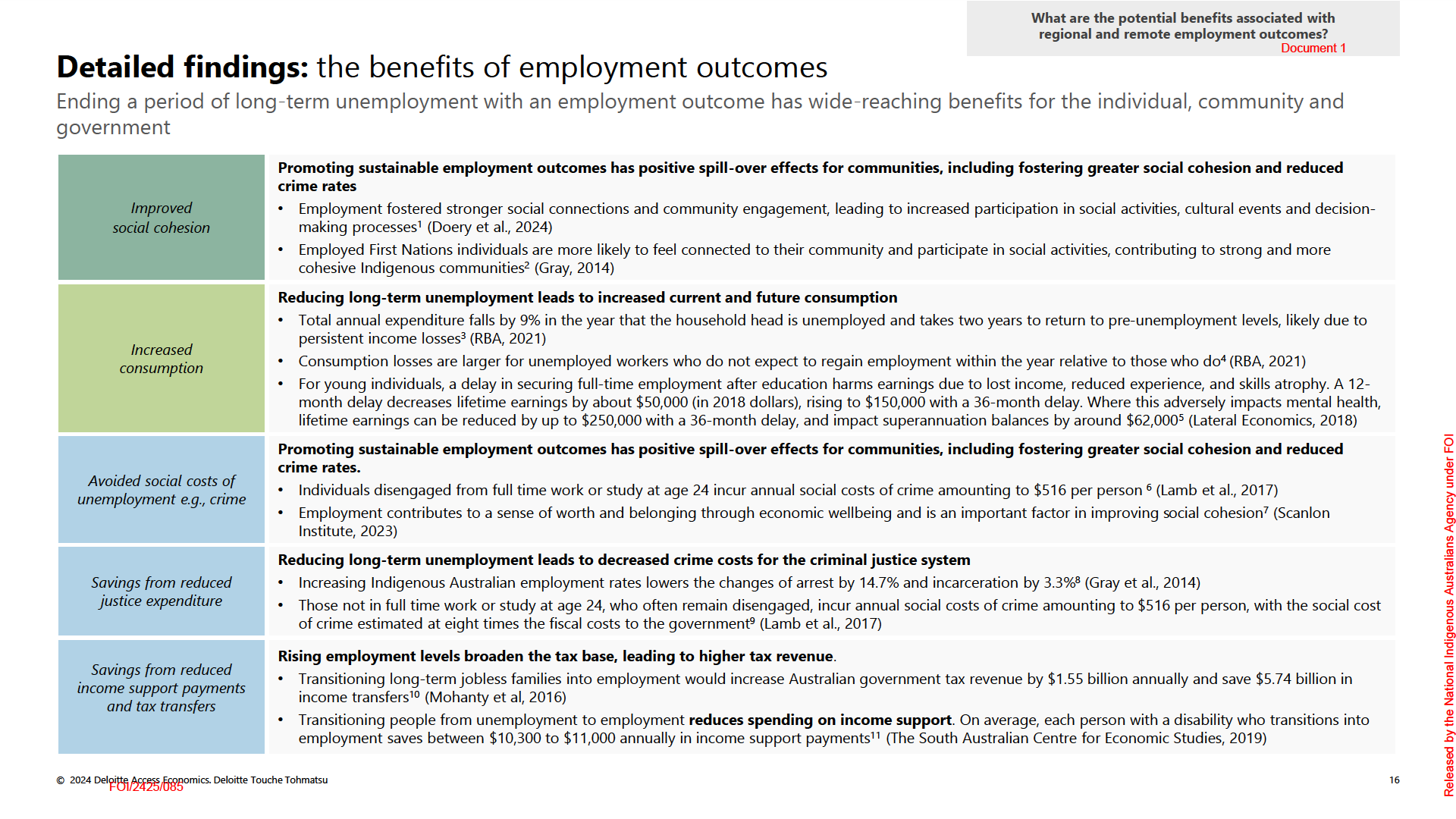

The insights and findings from a detailed literature review, including a

comprehensive list of benefits and benefit types associated with employment

programs.

Australians

2 | What value is quantifiable with respect to regional and remote

16

Indigenous

employment outcomes?

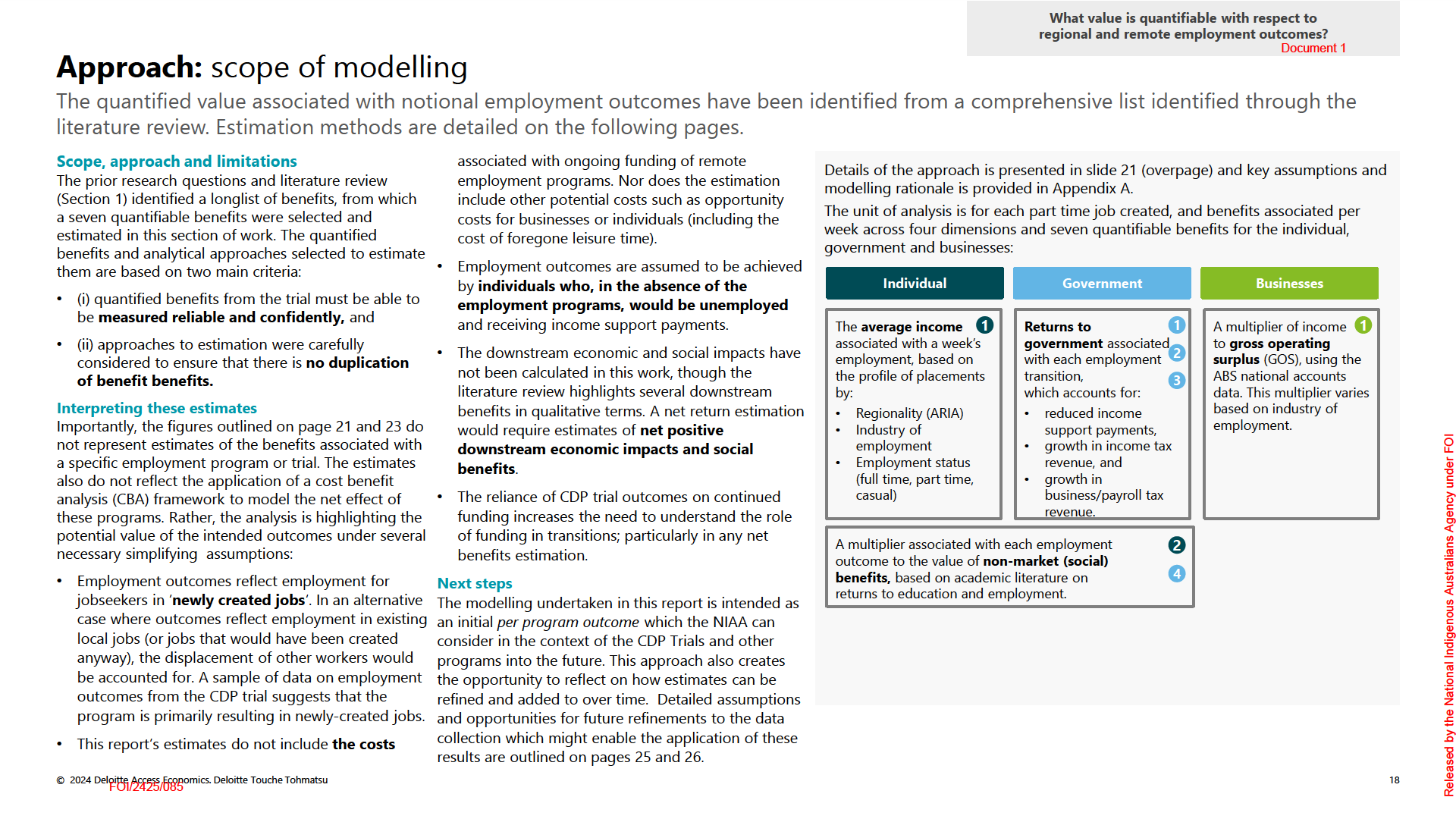

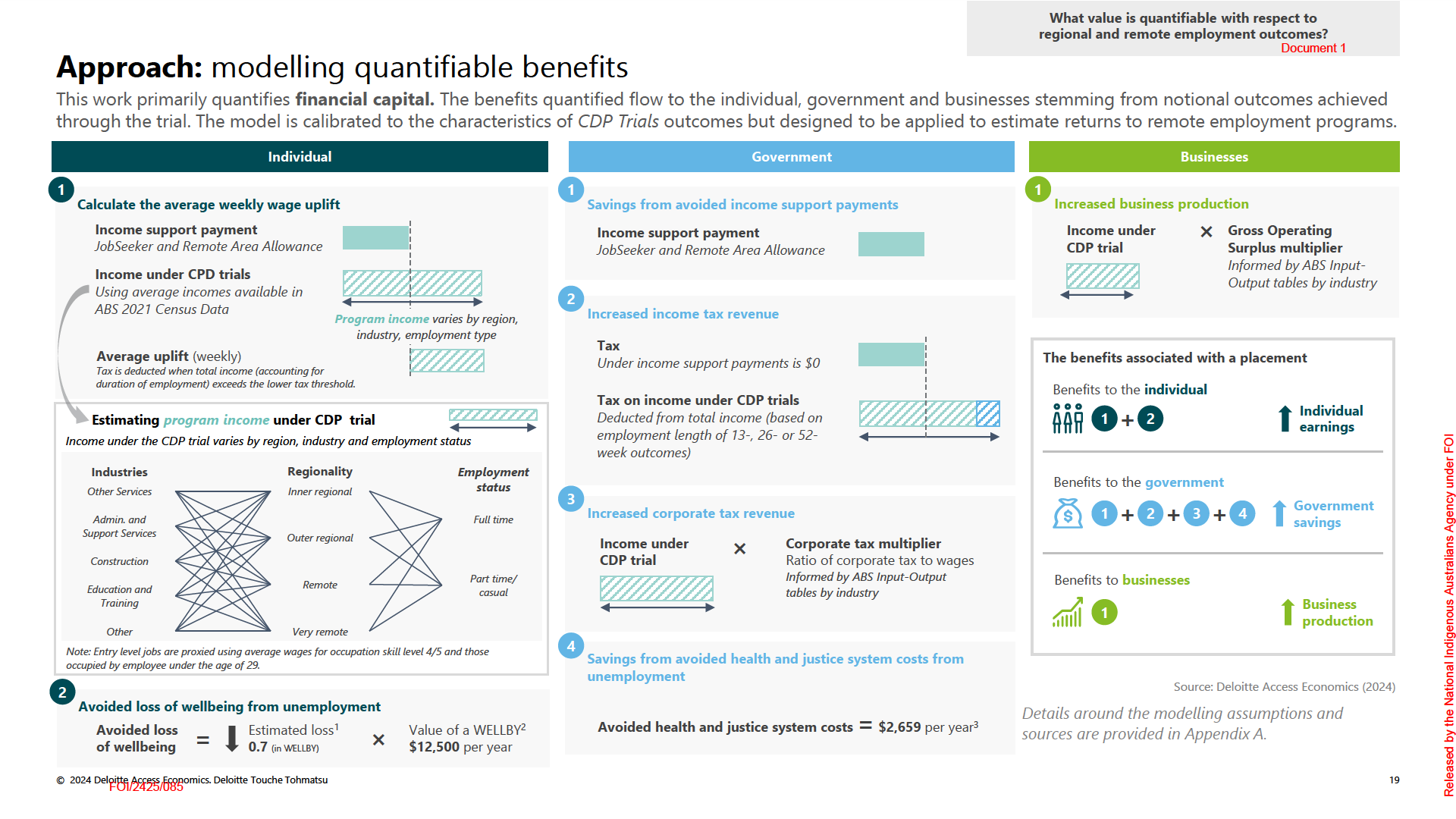

An overview of the analytical modelling approach to and the results from

* This report refers to remote employment outcomes for consistency with the naming of the

estimating the quantifiable benefits to employment programs.

Remote Jobs and Economic Development program. It is noted that when measuring the

remoteness of populations in the CDP regions (using an ARIA concordance); the outcomes are

primarily in remote and very remote areas, though others are in outer regions. Page 20

by the National

provides more detail about the regionality of

CDP Trials participants.

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

2

FOI/2425/085

Released

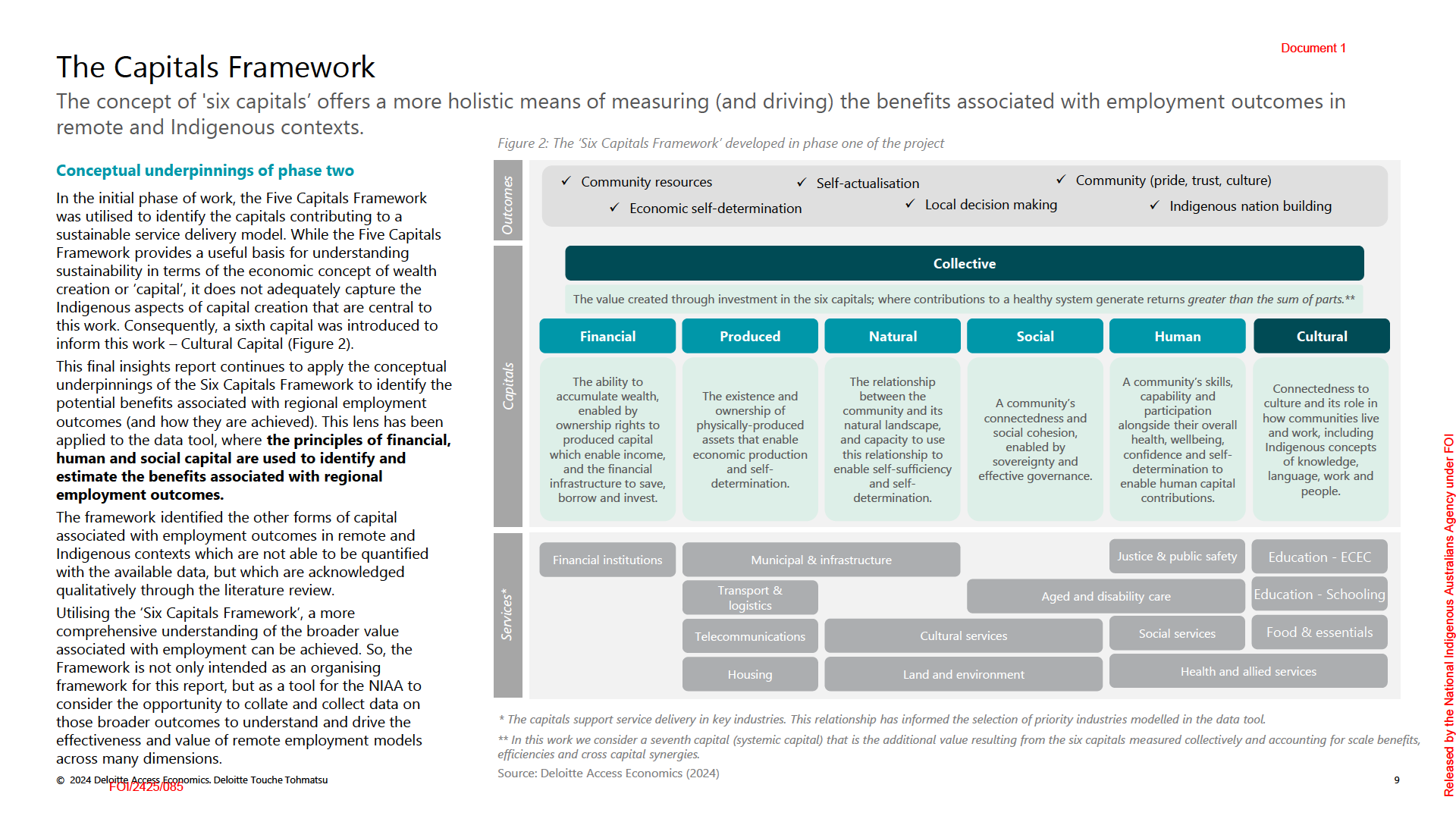

Foreword: The value of employment outcomes in regional and remote communities(1/2) Document 1

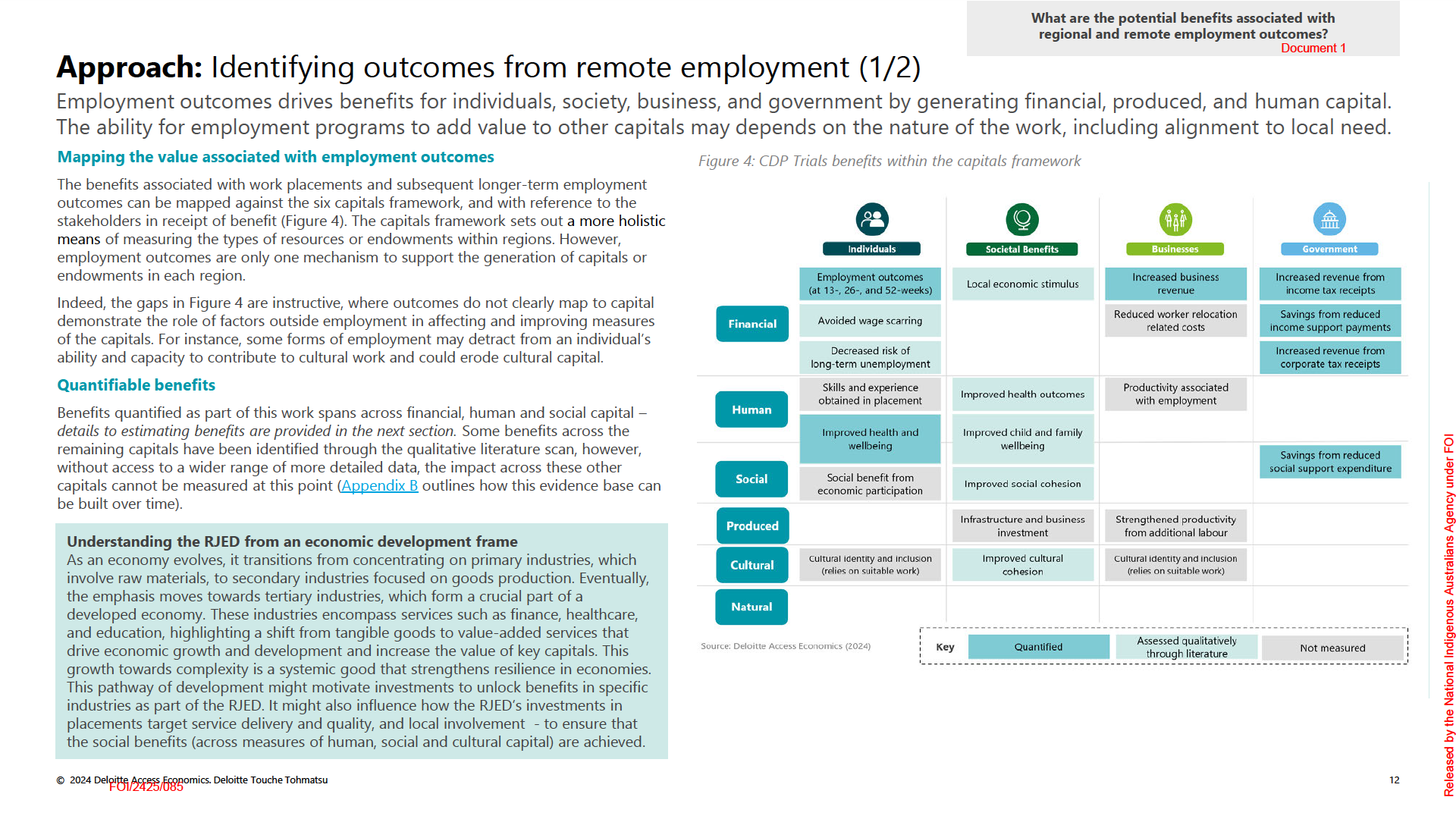

This report estimates and describes the economic benefits that can flow from regional

While considering financial returns to employment for individuals, government and

and remote job creation.

This includes an estimate of the quantifiable benefits likely to be businesses; through value associated with 13, 26 and (where transitions persist) 52-week

associated with employment in regional and remote communities; using the available

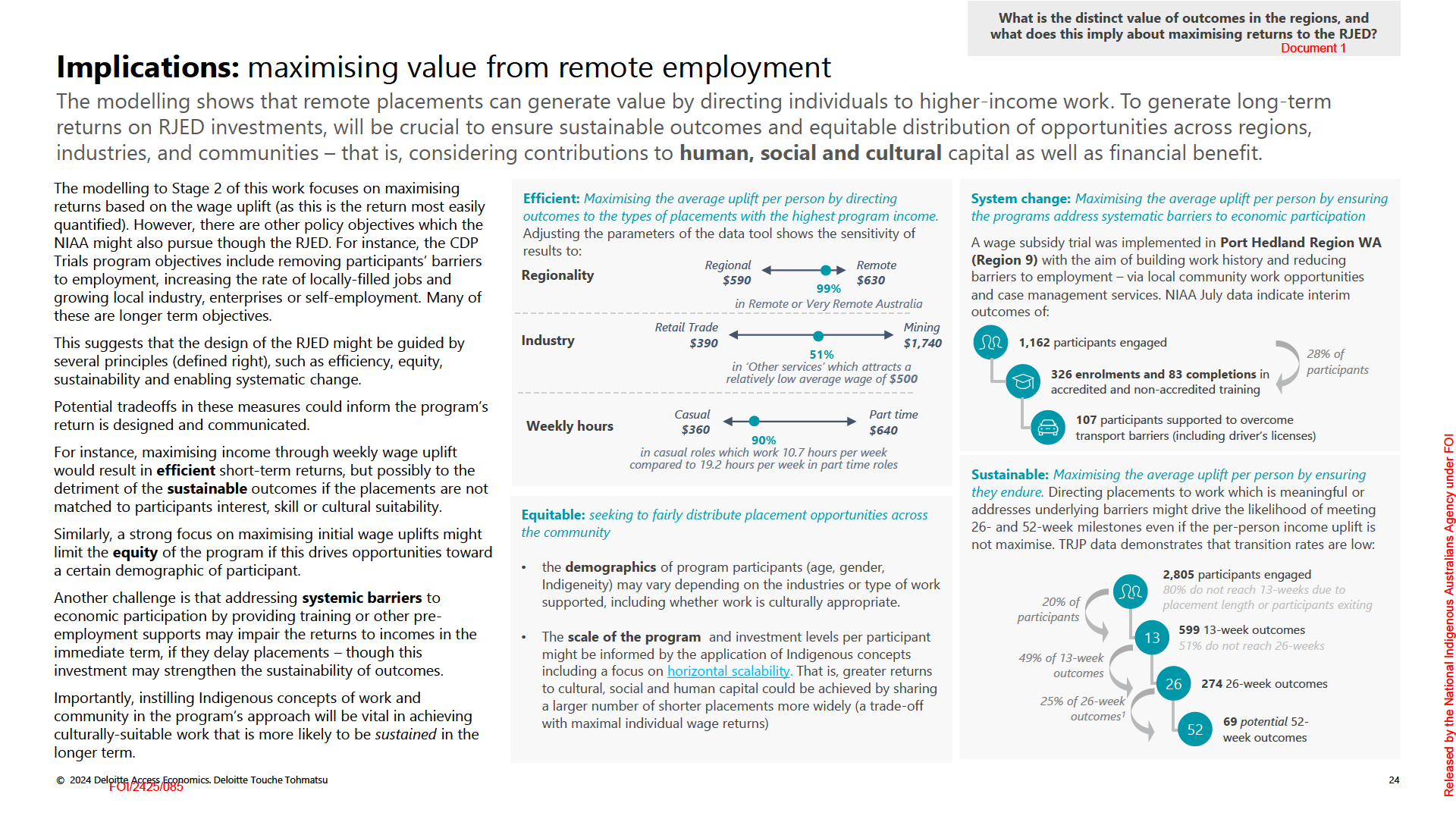

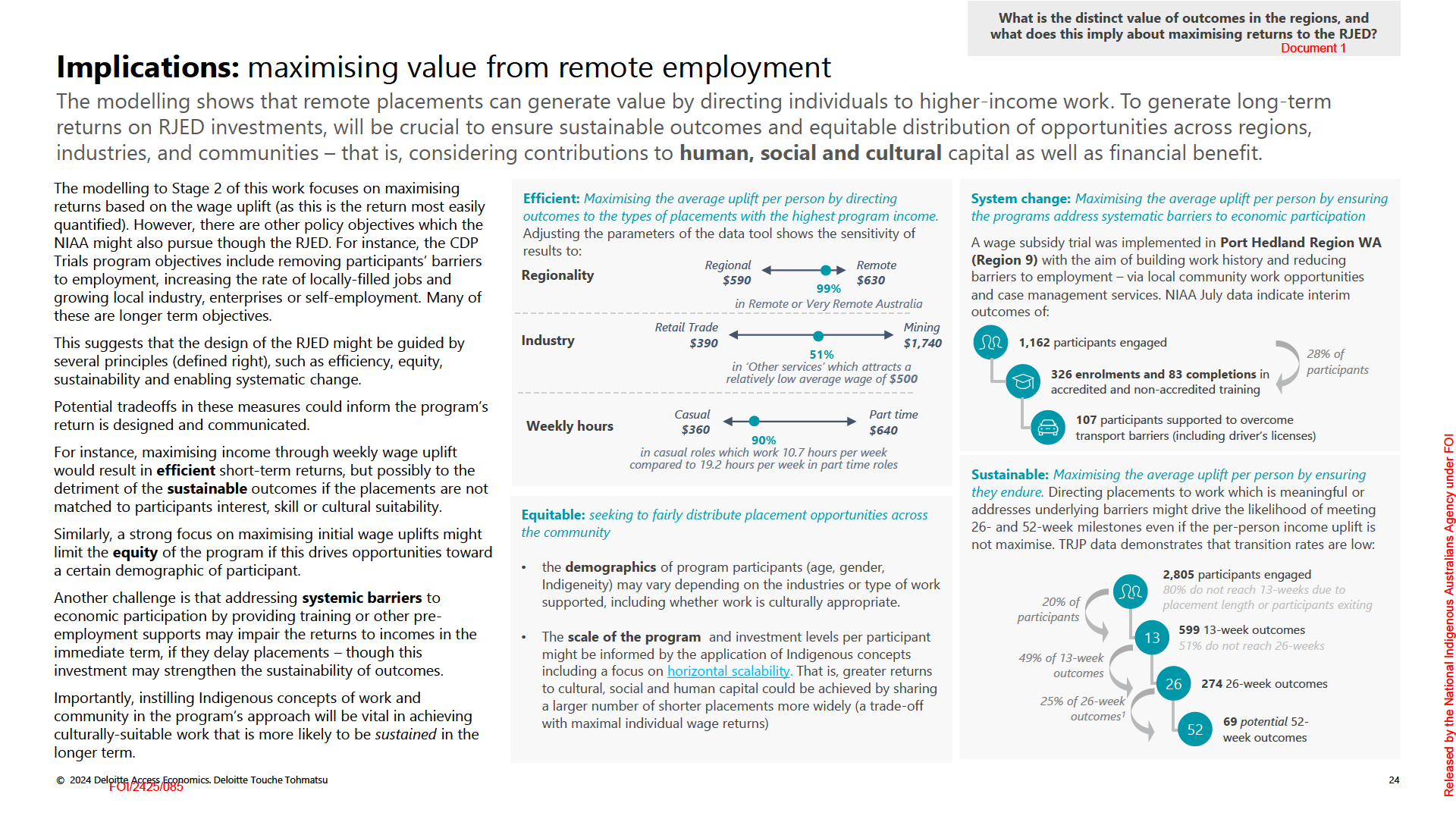

placements, this report’s modelling framework draws the implication that maximising

outcomes from the

CDP Trials to consider the potential value of the

Remote Jobs and

returns from 52-week-placements would be achieved by directing placements to the

Economic Development (RJED) program.

highest earning industries (roles or occupations). It inherently focuses on what is termed

But this project – and critically the RJED – is about much more than solving for short-term

financial and produced capital. Whether this approach maximises value over the long

economic return.

It is about outlining the way we might reimagine economic

term depends on assumptions about whether placements across different industries are

self-determination, community infrastructure, and meaningful employment opportunity.

equally likely to endure as lasting employment, and whether those roles contribute to

Speaking plainly, it is about understanding employment possibility for Indigenous

systemic opportunity and

scale. That is, whether those roles add value to

social, human or

communities from the ground up, rather than from government down.

cultural capital.

In my culture, work means something.

For instance, research on employment benefits finds that outcomes rely on employment

transitions being sustained and suitable for participants, suggesting a placement into the

It is measured in intrinsic reward as much as extrinsic. It is for community. It is meaningful.

most culturally-suitable work may be more likely to be

sustained, while systemically

It is not something measured only in income or time or position.

significant roles are more likely to contribute to whole community growth.

It is measured in the contribution to family and community and the system we share.

To inform how the NIAA uses these findings in an investment framework for the RJED,

this report considers trade-offs in maximising program value, including:

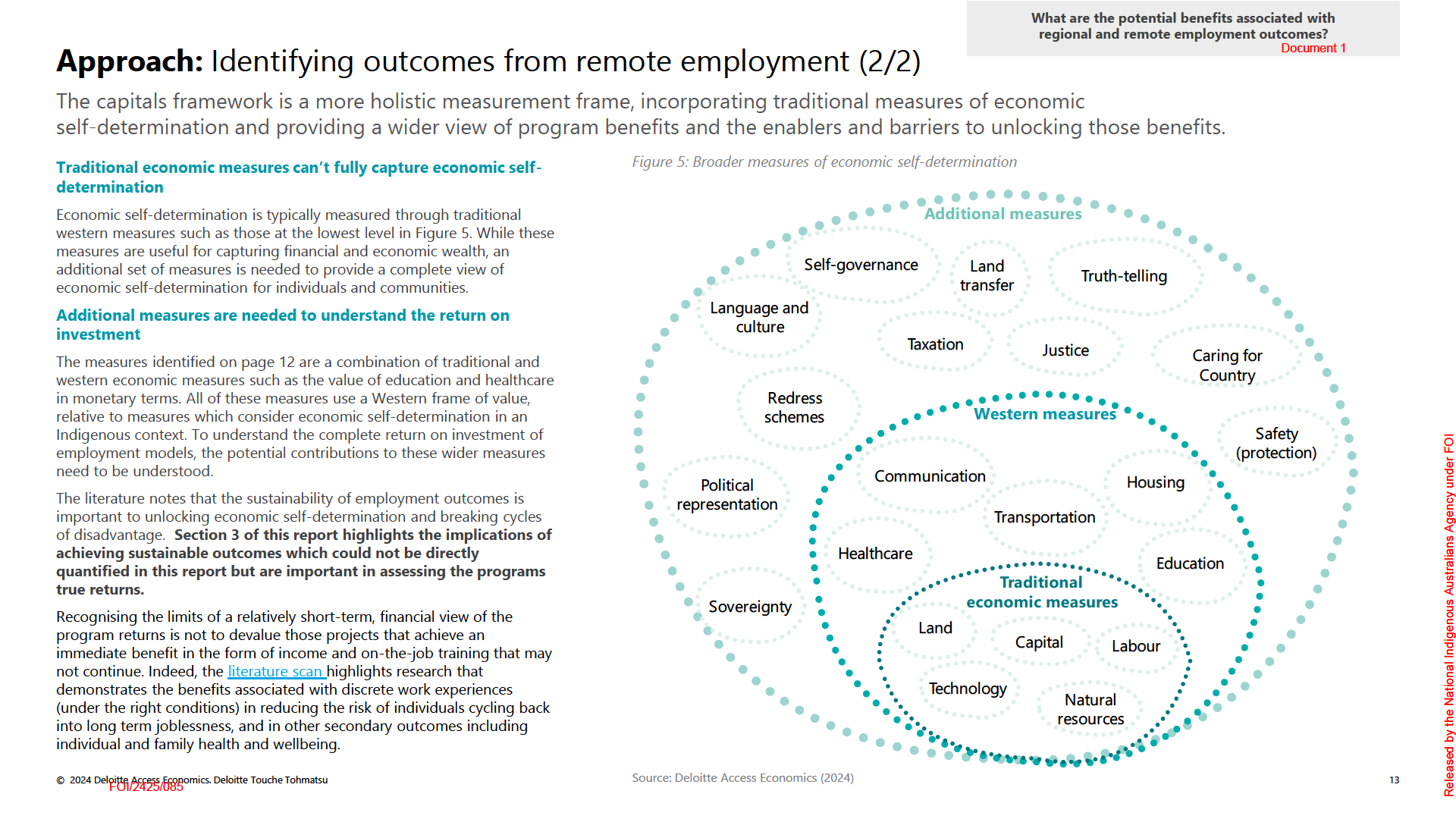

The normal metrics of economic frameworks are informative but ultimately too narrow to

properly diagnose problems or generate systemic, structural, long-term solutions.

• Whether a longer-term approach to maximising returns might direct focus toward the

dimensions of

meaningful work for participants and lead to enduring outcomes.

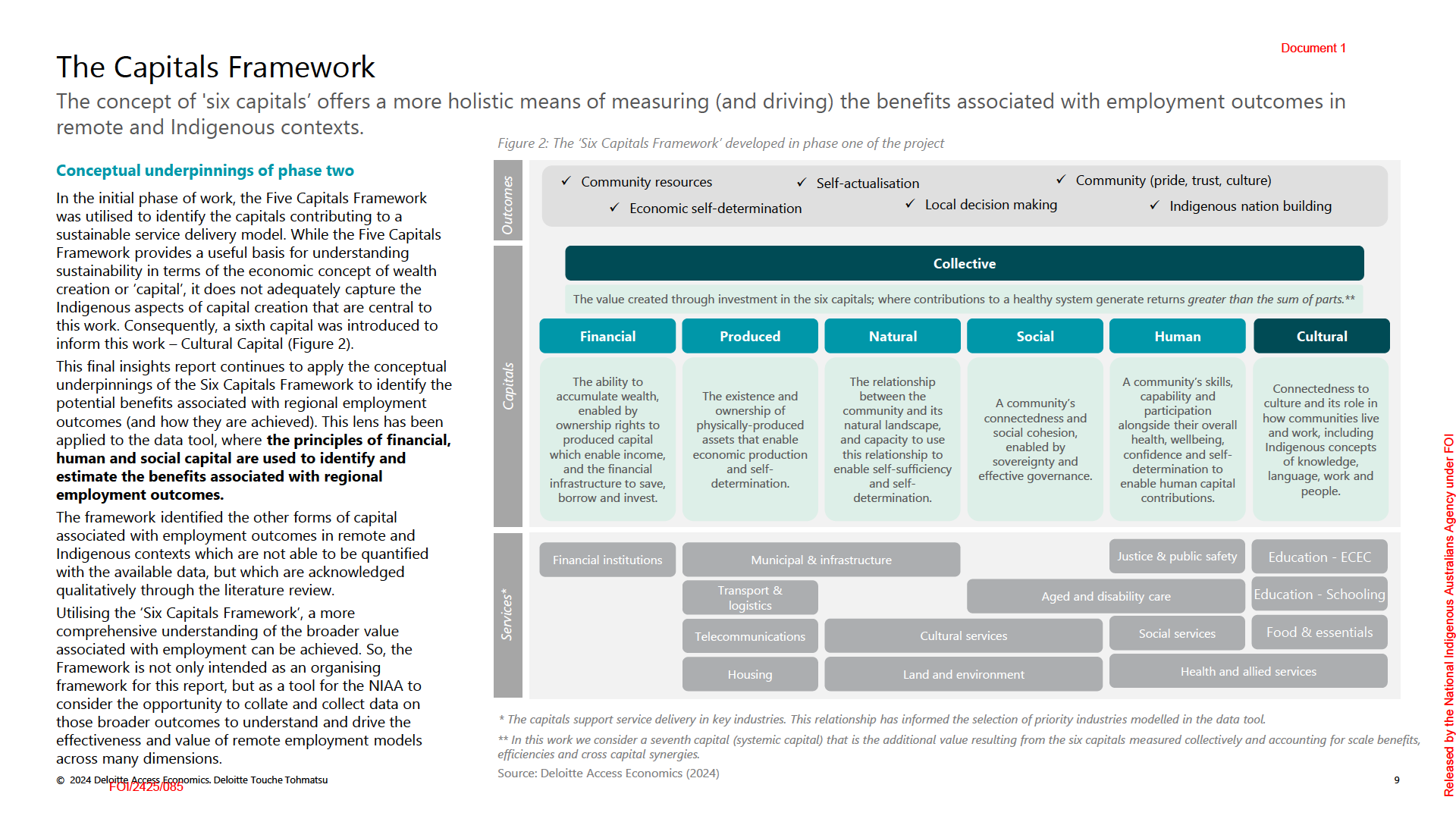

In this project we attempt to describe them more completely, using the sophisticated

capability of Deloitte Access Economics and innovative frameworks of thinking about the

• The role of employment programs in

addressing systemic barriers to economic

Agency under FOI

way community wants to build, and wants to work. Reflecting on the jobs trial, this

participation, by investing in other employment-related supports (training programs,

project considers how the RJED can create value by investing in community capability –

drivers licenses); a feature of many CDP trial trials. These activities may not generate

so that services are

delivered by community rather than merely to community.

immediate returns but can be essential preconditions to enduring employment.

Australians

This Insights Report provides a foundational framework and a new data tool to quantify

• The

equitable distribution of placement opportunities across the community;

benefits associated with employment placements in that program. While the TPRJ

recognising that the demographics of program participants (age, gender, Indigeneity),

Indigenous

program consists of initiatives that support short and long-term remote employment

and the accrual of benefits from that work to local community may vary across the

objectives, our focus on evidential analysis and the truth of present data limitations,

industries or type of work supported, including whether that work is culturally

requires that this report primarily focused on what can be quantified in the near term

appropriate, or located in proximity to community.

using traditional measures of economic participation.

continued over page

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

3

FOI/2425/085

Released

Foreword: The value of employment outcomes in regional and remote communities (2/2) Document 1

The findings in this work reiterate the value of investments that can

Scope of this work

complement the RJED’s focus on labour supply by

building the capacity,

This report is designed to support the NIAA to better understand the potential value of regional

resilience and suitability of the demand side (local employers). This

employment outcomes, and thereby to aid the NIAA’s understanding of the potential value of

includes building the cultural competency of non-indigenous employers and

employment programs such as the CDP Trials, and in time, the RJED. Page 5 sets out the high-level

the capacity of Indigenous business to benefit from engaging with public and

approach, key findings and implications associated with the findings.

private investors and measurement frameworks.

The findings presented in in this report present estimates of quantifiable benefits associated with

The findings in this report also highlight that some RJED employment

regional employment outcomes, calibrated to the profile of an ‘average’ CDP Trials placement

outcomes might result in the displacement of some workers (where funding is

outcome, across regionality and industry. Considerable further data col ection, analysis and

used to fill existing local jobs). However, this aligns with the policy objective

evaluation would however be necessary to determine the net return on interventions such as RJED.

of local job creation where it is indicated that out-of-community workers are

Interpreting the estimates

being replaced by in-community workers.

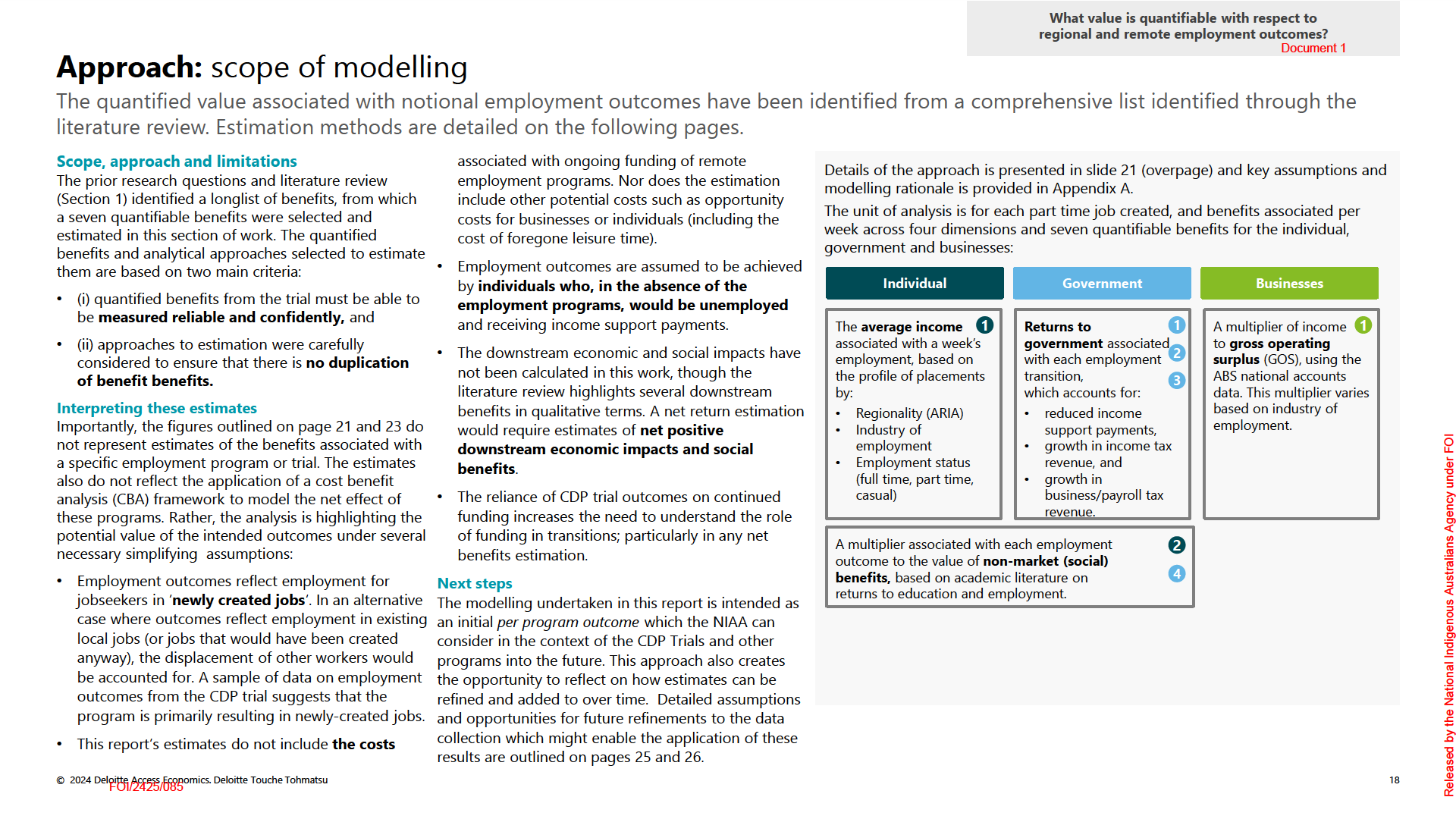

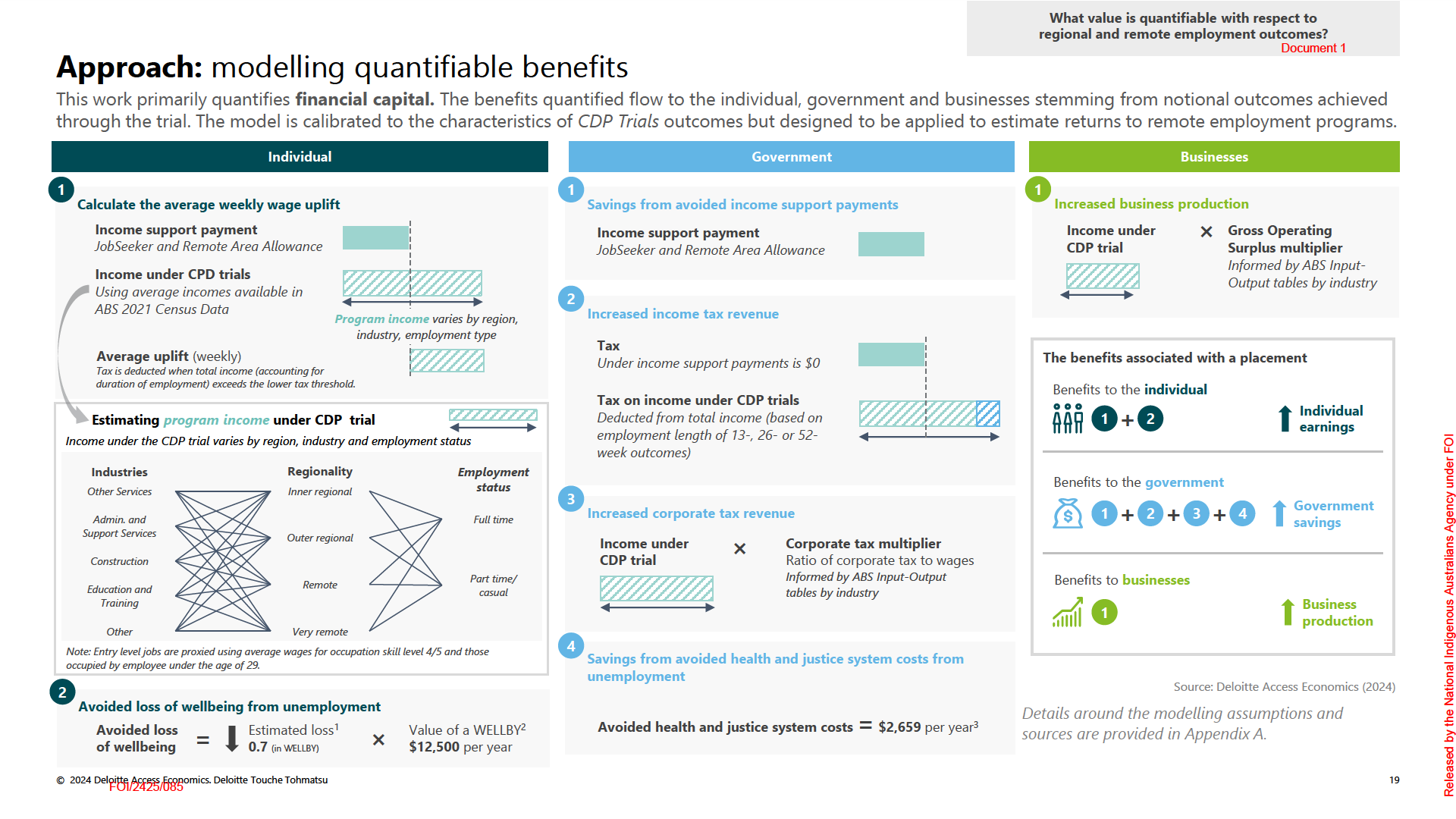

Importantly the figures outlined in this report do not represent estimates of the benefits associated

This finding also reiterates the relatively thin employment markets where the

with a specific employment program or trial. The estimates also do not reflect the application of a

RJED operates, which in turn encourages a focus on maximising value by

cost benefit analysis (CBA) framework to model the net effect of these programs. Rather, the analysis

ensuring an investment in the economic development and capability of local

is highlighting the potential value of the intended outcomes under a number of necessary

economies over the long-term through public investment rather than the

simplifying assumptions:

simpler targeting of net returns from job creation in the short-term,

• Employment outcomes reflect employment for jobseekers in ‘

newly created jobs‘. In an

Against that context, this work reinforces that a broader framework to

alternative case where outcomes reflect employment in existing local jobs (or jobs that would

understand value is essential to achieve those objectives in an enduring way –

have been created anyway), effects like the displacement of other workers would need to be

this report contributes the ‘six capitals’ framework to that discussion and

accounted for. A sample of data on employment outcomes from the CDP trial trial suggests that

Agency under FOI

concludes with a series of implications for future data collection and analysis

the program is primarily resulting in newly-created jobs.

to support that intent.

• This report’s estimates do not include

the costs associated with ongoing funding of remote

This framework points to the conclusion that in the absence of a net short-

employment programs. Nor does the estimation include other potential costs such as opportunity

Australians

term return in employment terms, investments which build any of the capitals

costs for businesses or individuals (including the cost of foregone leisure time).

can support economic growth; because these endowments are predictive of

• Employment outcomes are assumed to be achieved by

individuals who, in the absence of the

economic advancement.

employment programs, would be unemployed and receiving income support payments.

Indigenous

• The downstream economic and social impacts have not been calculated in this work, though the

Professor Deen Sanders OAM

literature review highlights several downstream benefits in qualitative terms. A net return

Worimi Man

estimation would require estimates of

downstream economic impacts and social benefits

Deloitte Access Economics Partner

(both positive and potentially negative).

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

4

FOI/2425/085

Released

What value is quantifiable with respect to

regional and remote employment outcomes?

Key findings: modelling and program outcome results

Document 1

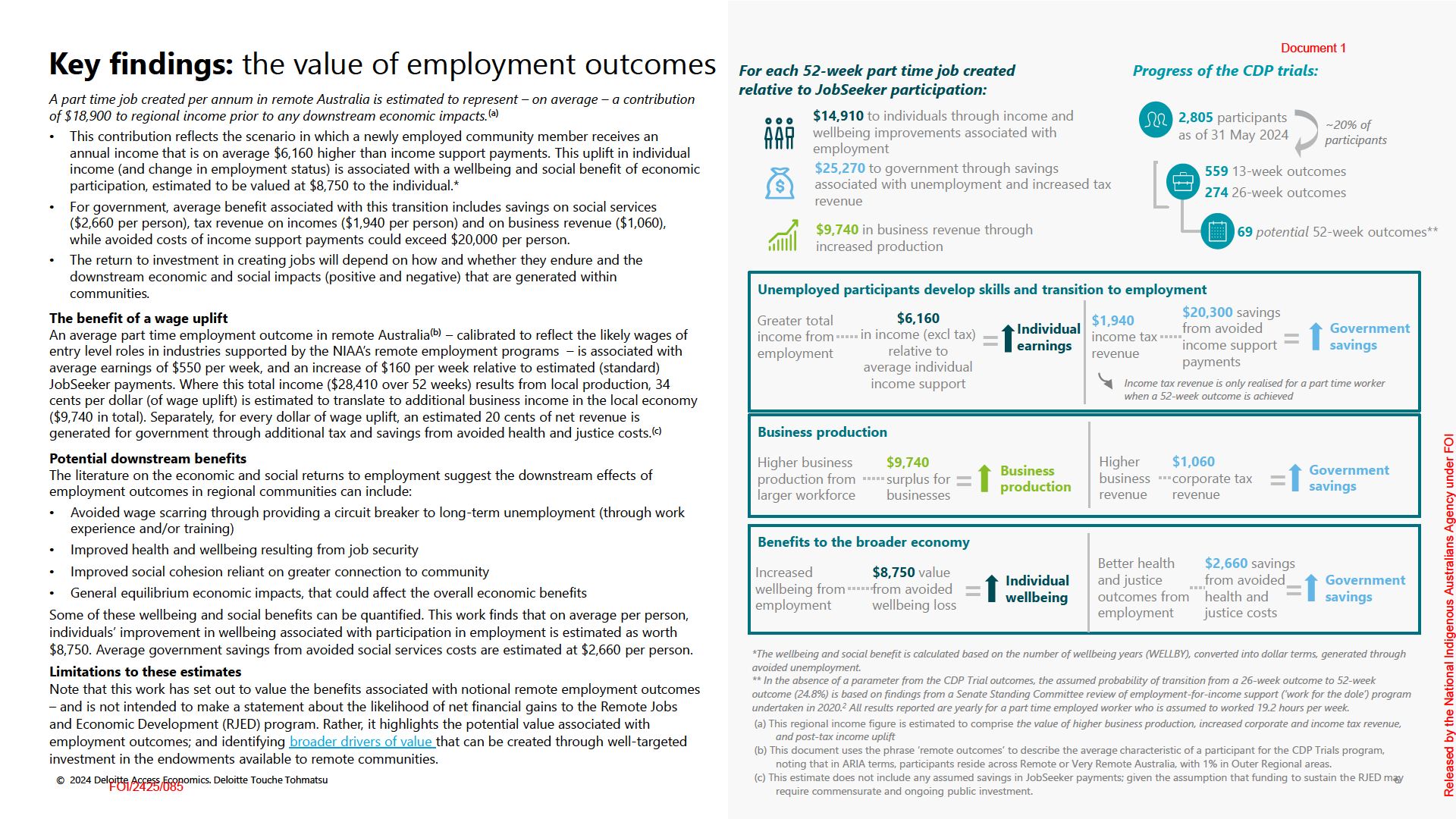

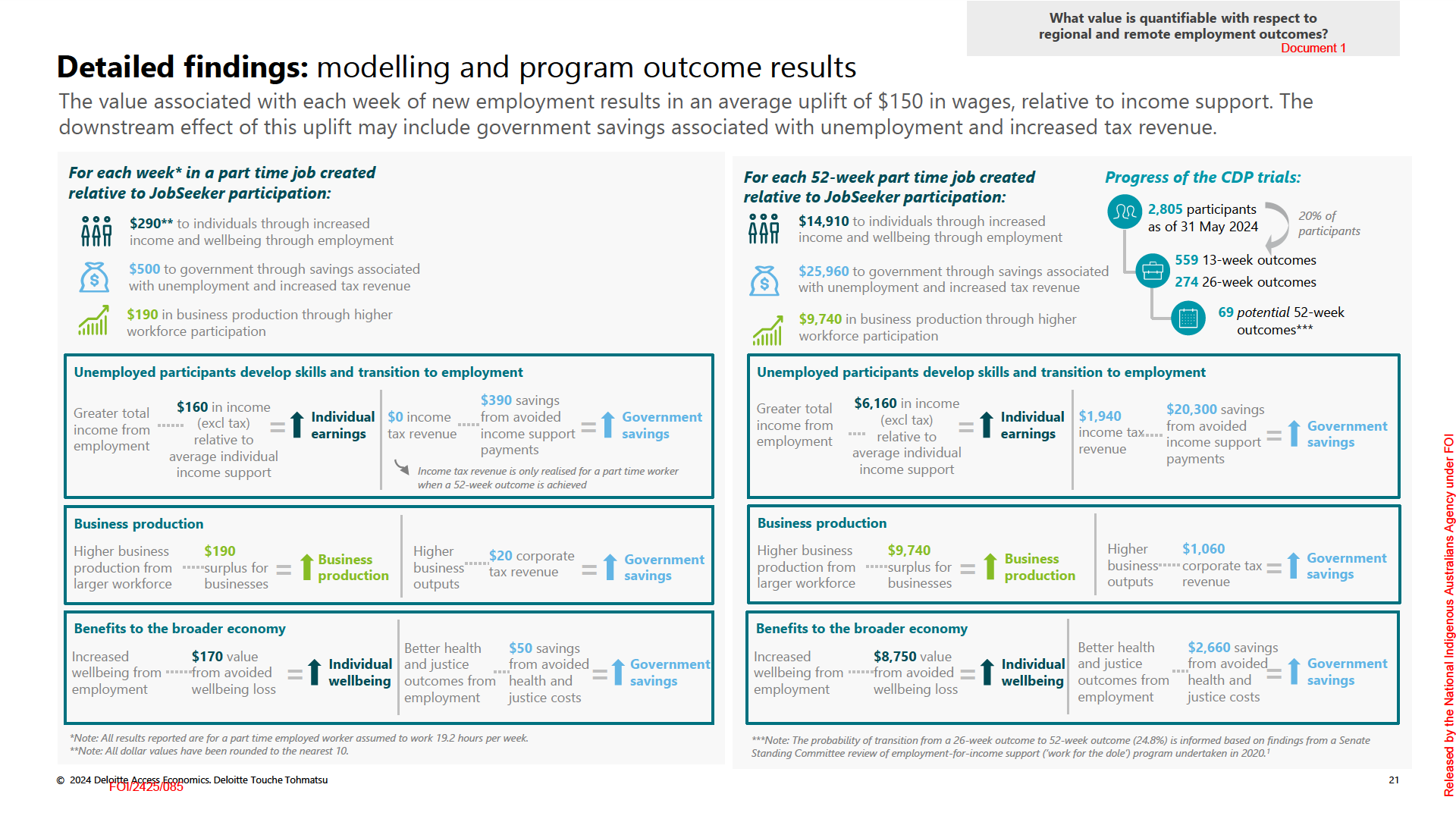

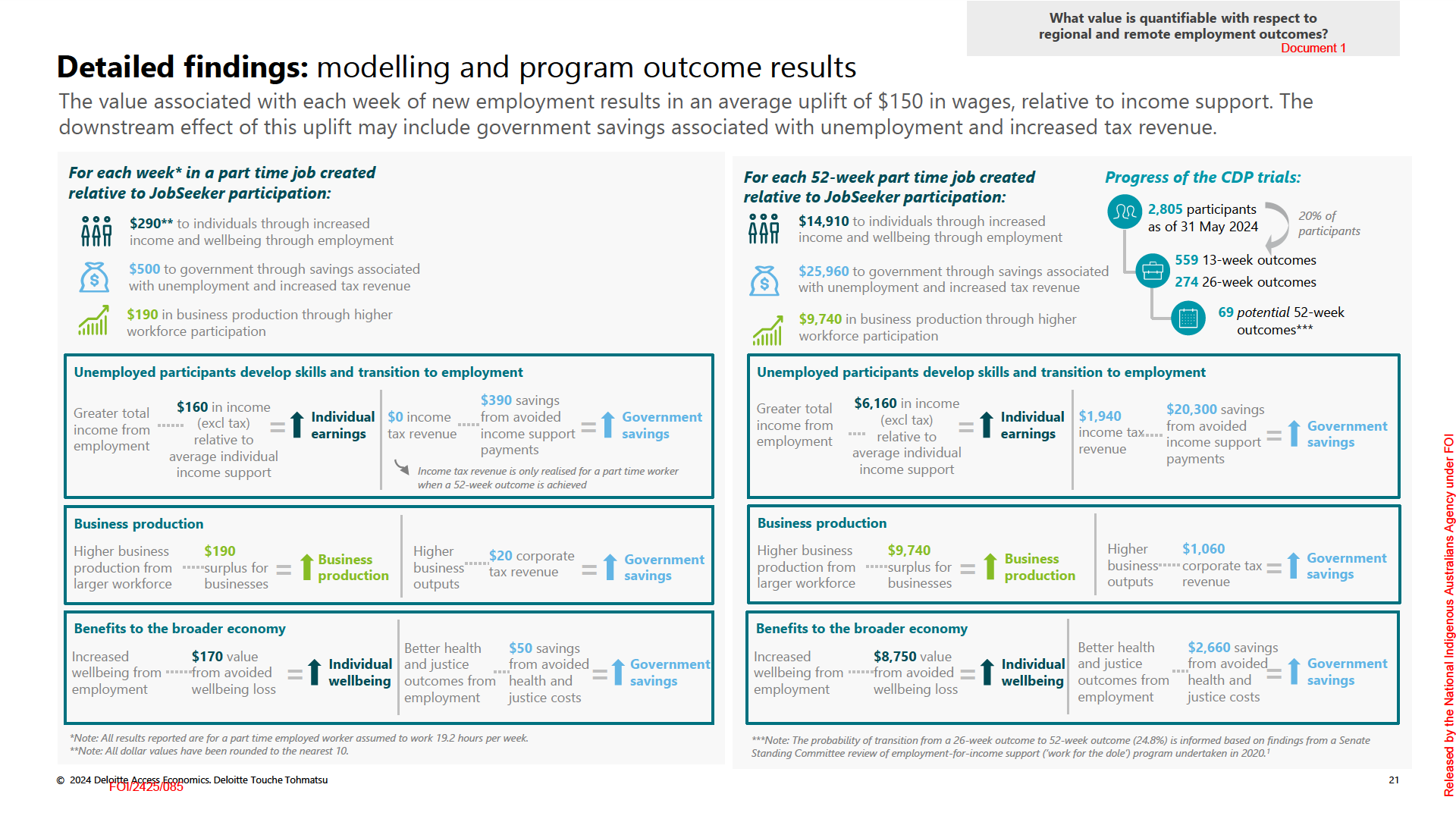

Quantified benefits reflect regional variation, industry, employment status, and outcome duration, calibrated to the profile of participants in the

CDP Trials, but are designed to be generalised. The accompanying model allows for the parameters to be adjusted.

Key findings

Profile of the CDP Trial outcomes

The quantified benefits and modelling captures the variation in regionality (ARIA), industry of

Between FY22-24, there were a total of 2,805 CDP Trials participants, of which 559 achieved

employment, employment status (full time, part time and casual) and duration of outcome

13-week outcomes and 274 achieved 26-week outcomes.

(13-, 26- or 52-weeks). The

per unit results are reported consistently in this document for a part

time job over a 52-week placement duration and is calibrated to reflect the profile of a CDP

The trial created work experience and jobs in the most remote and regional areas, with 99%

Trials participant across regionality and industry of employment.

of outcomes in Remote and Very Remote Australia.

Chart 1: Profile of 13- and 26-week outcomes by regionality

Deloitte Access Economics estimates that for every part time job created through the

Very Remote Australia

trial, a contribution of $18,900 to Gross Regional Product (GRP) is created.

86%

Remote Australia

13%

An average job outcome sees an $9,740 in the annual value added to the local economy, and

Outer Regional Australia

1%

results in 20 cents to the dollar in improvements to government finance through additional tax

and reduced income support payments.

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2024) using NIAA program outcome data. Note: CDP regions have been mapped to ARIA

regional categories based on the proportion of caseload in ‘Very Remote’ regions (NIAA remoteness index).

Other downstream effects for communities include avoided wage scaring and improved

Greater visibility of occupation industries would improve the ability to capture variations in

wellbeing; with evidence pointing to the intergenerational benefit of addressing joblessness.

program outcomes – 51% of outcomes are in

Other Services and 19% in Other industries.

The value of employment to the local economy (in GRP terms) equates to:

Chart 2: Profile of 13-week outcomes by Industry

• $4,700 for an individual with a 13-week outcome, which 559 trial participants have achieved,

Other Services

284 (51%)

or

Administrative and Support Services

70 (13%)

Education and Training

• $9,500 for an individual with a 26-week outcome, which 274 trial participants have achieved.

37 (7%)

Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing

34 (6%)

Agency under FOI

This modelling demonstrates how value could be created when 13- and 26-week outcomes

Health Care and Social Assistance

27 (5%)

persist to a years’ employment. It is notes that data provided by NIAA for a sample of 15

Other industries*

107 (19%)

regions finds only two instances where a substantial share of jobs created under the CDP Trials

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2024) using NIAA program outcome data. *Note: There are 107 outcomes in the

would be “sustainable without continued funding and support”. In most instances where jobs

Australians

remaining industries with unknown shares due to data suppression.

filled under the CDP Trials are reported as likely to be sustained, these placements appear to

All program outcomes are in casual (90%) or part time (10%) roles. The longer-term value of

be primarily leveraging existing local jobs (suggesting some degree of displacement), rather

the trials will rely on the transition rate from 26-week outcomes to sustainable employment.

than unique job creation. A net return to the RJED may rely on whether newly created jobs can

Indigenous

be sustained in the absence of ongoing subsidisation; and there appears an opportunity to

Chart 3: Profile of 13- and 26-week outcomes by employment status

learn from those trials where new job creation is expected to sustain, about the conditions

Part-time (10%)

needed to realise success.

Casual (90%)

by the National

Source: Deloitte Access Economics (2024) using NIAA program outcome data. Note: There are no full time CDP Trials outcomes. The

Note: All dollar values have been rounded to the nearest 10.

modelling assumes part time employed works 19.2 hours per week, and casual employed works 10.7 hours per week (see Appendix A).

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

20

FOI/2425/085

Released

What is the distinct value of outcomes in the regions, and

what does this imply about maximising returns to the RJED?

Provisional conclusions and their implications

Document 1

In estimating the immediately quantifiable value associated with employment placements, the modelling exercise revealed sensitivity to certain

assumptions. The early evidence highlighted opportunities to consider how the ROI of the program could be communicated in the long term.

Insights in this report

A provisional conclusion

Implications for understanding returns

Opportunity for RJED

• The current transition rate of 26-week placements to 52-week

The longer-term value created by the

• There is opportunity to better understand the rates of Stronger evidence will support

outcomes (24.8%) is based on findings from a Senate

trials will depend on the rate of

longer-term outcomes, either by collecting data on

the NIAA to communicate the

Standing Committee review of employment-for-income

transition from 26-week outcomes to

outcomes over time from providers or linking

sustained value of the RJED

support (‘work for the dole’) programs undertaken in 2020.1

enduring and suitable employment.

participant details to DSS administrative dataset

where outcomes endure.

• There is evidence of some displacement and deadweight in

(through PLIDA, for example).

other evaluations of wage subsidies - that is, a risk

• An historical and continuous exercise to estimate the

employment is not enduring.2

likelihood of ongoing outcomes can strengthen the

NIAA’s view of program benefit and sustainability.

• The literature demonstrates that reducing

The consumption and employment

• There is opportunity to better understand the value

Understanding these local

long-term unemployment leads to increased current and

returns associated with placement

associated with the CDP on local economies and

consumption dynamics can

future consumption, and that unemployment rates are higher

outcomes may have a more substantial

businesses. Recognising challenges in data collection

support the NIAA to

in very remote areas

impact in developing the capability of

at the granular level, there is an opportunity for the

communicate how value is

• Regional and remote Australian jurisdictions have the least

regional economies

NIAA to agree on the most regional mechanism to

created through the regional

complex (sophisticated) economies3, with a inverse

track outcomes over time (a combination of Census

employment program and the

relationship between sophistication and consumption

and income tax data, NIAA regional offices data

flow to local industry expected

patterns suggesting that regionally-employed workers are

collection, inputs from program evaluations)

from these investments.

more likely to invest and spend locally.

Agency under FOI

• Data on employment placements focuses on historical

The data from providers and generally

• Notwithstanding the limitations, the exercise of

Stronger evidence will support

outcomes (placements, jobs created, vacancies filled), but

available from the system tends to be

mapping immediate value associated with job

the NIAA to communicate the

there is limited information to understand the likely rates of

insufficient (in terms of informing a

placements does progress the work by (1) clearly

sustained value and to

Australians

transition to sustained employment after the trial concludes.

deeper understanding of community and

hypothesizing what the value could be under the

understand the benefit of

• While some benefit might be inferred through measures of

employment benefit), out of step (not

modelled conditions, and (2) making clear the

programs in

addressing

educational enrolment or outcome, the 13- and 26-week

measuring the activity in the immediate

opportunity to refine the parameters through future

systematic barriers to

Indigenous

outcome measure which is used to inform the initial

system but being consequence of other

data collection.

participation.

modelling framework does not allow coverage of the value of

initiatives), or even potentially wrong

partial outcomes.

(with potential bias to reward signals for

providers, rather than the participant).

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

25

FOI/2425/085

Released

What is the distinct value of outcomes in the regions, and

what does this imply about maximising returns to the RJED?

Provisional conclusions and their implications

Document 1

In estimating the immediately quantifiable value associated with employment placements, the modelling exercise revealed sensitivity to certain

assumptions. The early evidence highlighted opportunities to consider how the ROI of the program could be communicated in the long term.

Insights in this report

A provisional conclusion

Implications for understanding returns

Opportunity for RJED

• The wage or potential earnings uplift is

The return on investment in immediate

• Including a broader set of benefits in the outcomes

Broader outcomes measures will support the

predictive of a range of downstream economic

wage uplift terms may be limited due to

quantified (to understand the long-term ROI of the

NIAA to communicate the returns to

an

and social benefits for individual, family,

the high rate of casual placements.

program) would require a view of the likely transition

equitable program, and longer-term

community, if and only if the employment is

rates from CDP Trials placements at 13 and 26 weeks

outcomes data will demonstrate the potential

secure and ongoing.

to ongoing employment.

for a

sustainable return.

• The models of employment support offered

• The data tool can be used to dimension some

Visibility of variation in the quantifiable

in the trials vary, and there is identified

regional variation.

benefits across regions might direct attention

limitation in the reliability of data on the

• Recognising challenges in data collection at the

to examples of

different ways value is

industries and occupations associated with

The value of the outcomes is likely to be

granular level, there is an opportunity for the NIAA

shared and generated, in line with

the placements.

broader than that quantified in the

the agree on the most regional mechanism to track

indigenous principles.

• The benefits associated with short-term

immediate wage uplift estimate.

outcomes over time (a combination of Census and

placements or partial outcomes are

income tax data, NIAA regional offices data

challenging to observe, due to the focus on

collection, inputs from program evaluations)

13 and 26-week outcome reporting.

• Some of the RJED employment outcomes

• Data provided by NIAA for a sample of 15 regions

These findings demonstrate the thin markets

might result in displacement of existing

If local human capital is effectively

finds only two instances where a substantial share

where the RJED is implemented – implying a

workers in those roles. However, this

engaged and used to enhance the stock

of jobs created under the CDP Trials would be

focus on maximising value from public

potential outcome aligns with one of the

of produced and financial capital in the

“sustainable without continued funding and

investment rather than an obvious path to

Agency under FOI

policy objectives of replacing FIFO workers

community, the RJED will not only

support”. These sustainable placements appear to

avoiding a commissioning approach. The

with local employment.

redistribute opportunities from FIFO to

local workers but also expand local

be primarily leveraging existing local jobs

capitals framework can be applied to

opportunities through flow-on

(suggesting some degree of displacement), rather

demonstrate these broader dimensions of

Australians

economic benefits.

than unique job creation.

value but must be informed by more

sophisticated data collection.

• The high rate of casual employment

There is a strong likelihood that the result

• There is opportunity to collect data from providers

Stronger evidence on outcomes over time for

placements in the CDP Trials mean that the

at the individual region level will vary

about the hours worked or income earned in casual casual workers might support in

Indigenous

estimated return to employment in the

greatly relative to the on-average

placements.

demonstrating the value of

addressing

program is highly sensitive to the

national modelling result.

• In the modelling, both parameters will be estimated

systematic barriers to participation, even

assumptions about the number of hours

using ABS data which does not always distinguish a

when wage returns are not maximal.

worked.

casual from a part time worker.

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

26

FOI/2425/085

Released

s47G

Agency under FOI

Australians

Indigenous

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

28

FOI/2425/085

Released

s47G

Agency under FOI

Australians

Indigenous

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

29

FOI/2425/085

Released

s47G

Agency under FOI

Australians

Indigenous

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

30

FOI/2425/085

Released

s47G

Agency under FOI

Australians

Indigenous

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

31

FOI/2425/085

Released

s47G

Agency under FOI

Australians

Indigenous

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

33

FOI/2425/085

Released

References

Document 1

Page 6 - Key Findings

6. Gabrielle Penrose and Gianni La Cava,

Job Loss, Subjective Expectations and Household Spending, Reserve

1. The Senate,

Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Annual reports (No. 1 of 2020),

Bank of Australia, August 2021, <https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2021/2021-

<https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/publications/tabledpapers/d876a0a3-019b-480c-aa38-

08/full.html#section-how-does-unemployment-affect-household-spending>

45aef7025140/upload_pdf/education%20-

7. Deloitte Access Economics, 2023 SROI Evaluation of the NCHP (report commissioned by Community Hubs,

%20annual%20report.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22publications/tabledpapers/d876a0a3-

March 2024), <https://www.communityhubs.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Full-report-2023-SROI-

019b-480c-aa38-45aef7025140%22>

National-Community-Hubs-Program.pdf>

8. M. Gray, B. Hunter, and N. Biddle

, The Economic and Social Benefits of Increasing Indigenous Employment,

Page 8 - Context to this work

Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, ANU College of Arts & Social Sciences, CAEPR Topical

Issue No. 1/2014, <https://caepr.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/Topical_Issue_01-

1. Prime Minister of Australia,

Next Steps on Closing the Gap: delivering remote jobs, 2024,

2014_GrayHunterBiddle_EconomicSocialBenefitsIndigenousEmployment_0.pdf>

<https://www.pm.gov.au/media/next-steps-closing-gap-delivering-remote-jobs>

9. I. Mohanty, R. Tanton, Y. Vidyattama, and L. Thurecht,

Estimating the Fiscal Costs of Long-term Jobless

2. National Indigenous Australians Agency,

Job trials: Testing new approaches to remote employment, 2023,

Families in Australia, Australian Journal of Social Issues, vol. 51, no. 1, 2016,

<https://www.niaa.gov.au/our-work/employment-and-economic-development/job-trials-testing-new-

<https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2016.tb00366.x?saml_referrer.>

approaches-remote-employment>

3. National Indigenous Australians Agency,

Community Development Program (CDP): Trialling Pathways to

Real Jobs, 2023, <https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/publications/cdp-trialling-

Page 15 – Detailed findings: the benefits of employment outcomes

pathways-summary-approved-trials-mar-2023.pdf>

1. Government of Australia,

Working Future: The Australian Government’s White Paper on Jobs and

Opportunities, 25 September 2023, <https://treasury.gov.au/employment-whitepaper/final-report.>

Page 14 – Key Findings: the value associated with employment outcomes

2. J. Schmieder, T. von Wachter, and S. Bender

, The Effect of Unemployment Benefits and Nonemployment

Durations on Wages, 2015,

1. Daniel H. Cooper,

The Effect of Unemployment Duration on Future Earnings and Other Outcomes, Federal

<http://www.econ.ucla.edu/tvwachter/papers/SchmiederVonwachterBender_June2015.pdf

>

Reserve Bank of Boston Working Paper No. 13-8, October 10, 2013, <https://ssrn.com/abstract=2366542> 3. Daniel H. Cooper

, The Effect of Unemployment Duration on Future Earnings and Other Outcomes, Federal

2. Natasha Cassidy, Iris Chan, Amelia Gao, and Gabrielle Penrose,

Long-term Unemployment in Australia,

Reserve Bank of Boston Working Paper No. 13-8, October 10, 2013, <https://ssrn.com/abstract=2366542>

Agency under FOI

Reserve Bank of Australia, December 2020,

<https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2020/dec/pdf/long-term-unemployment-in-australia.pdf> 4. Natasha Cassidy, Iris Chan, Amelia Gao, and Gabrielle Penrose,

Long-term Unemployment in Australia,

Reserve Bank of Australia, December 2020,

3. Fiona Macdonald,

Inclusive and Sustainable Employment for Jobseekers Experiencing Disadvantage:

<https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2020/dec/pdf/long-term-unemployment-in-australia.pdf>

Workplace and Employment Barriers, The Australia Institute Centre for Future Work, 2023

,

Australians

<https://futurework.org.au/wp-

5. J. Schmieder, T. von Wachter, and S. Bender

, The Effect of Unemployment Benefits and Nonemployment

content/uploads/sites/2/2023/05/Barriers_to_Sustainable_Emplt_Centre_for_Future_Work-April_2023.pdf>

Durations on Wages, 2015,

<http://www.econ.ucla.edu/tvwachter/papers/SchmiederVonwachterBender_June2015.pdf

>

4. As above

6. Department of Employment and Workplace Relations, Employment Pathway Fund Evaluation: Chapter 2 -

Indigenous

5. M. Gray, B. Hunter, and N. Biddle

, The Economic and Social Benefits of Increasing Indigenous Employment,

Wage Subsidies, FOI Reference D21/527691, 5 April 2023, <https://www.dewr.gov.au/employment-

Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, ANU College of Arts & Social Sciences, CAEPR Topical

services-evaluations/resources/employment-pathway-fund-evaluation-chapter-2-wage-subsidies>

Issue No. 1/2014, <https://caepr.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/Topical_Issue_01-

2014_GrayHunterBiddle_EconomicSocialBenefitsIndigenousEmployment_0.pdf>

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

35

FOI/2425/085

Released

References

Document 1

Page 14 – Detailed findings: the value associated with employment outcomes (cont.)

4. As above

7. Boyd Hunter, Yonatan Dinku, Christian Eva, Francis Markham, and Minda Murra,

Employment and

5. Lateral Economics,

Youth Resilience and Mental Wellbeing: The economic costs of delayed transition to

Indigenous Mental Health, The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2022,

purposeful work (report commissioned for VicHealth), October 2018,

<https://www.indigenousmhspc.gov.au/getattachment/049a59e4-9d01-40f6-a3f4-6f4675eb3dfa/hunter-

<https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/Youth-Resilience-and-Mental-Wellbeing-Economic-

et-al-2022-employment.pdf>

Model.pdf>.’

8. As above

6. S. Lamb and S. Huo,

Counting the Costs of Lost Opportunity in Australian Education, Mitchell Institute

9. Fairfax Media & Lateral Economics

, Fairfax Lateral Economics Index of Australia's Wellbeing: Final Report,

report, No. 02/2017, 2017, <https://content.vu.edu.au/sites/default/files/media/counting-the-costs-of-

February 2014, <https://lateraleconomics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Fairfax-Lateral-

lost-opportunity-in-aus-education-mitchell-institute.pdf.>

Economics-Index-of-Australias-Wellbeing-Final-Report.pdf>

7. O’Donnell, J,

Mapping Social Cohesion 2023, Scanlon Institute, 2023,

10. Frijters, P and Krekel, C,

A Handbook for Wellbeing Policy-Making: History, Theory, Measurement,

<https://scanloninstitute.org.au/sites/default/files/2023-

Implementation and Examples, Oxford University Press, 2021, <https://academic.oup.com/book/39348>

11/2023%20Mapping%20Social%20Cohesion%20Report.pdf>

11. Foster, G,

COVID’s Cohort of Losers: The Intergenerational Burden of the Government’s Coronavirus

8. M. Gray, B. Hunter, and N. Biddle

, The Economic and Social Benefits of Increasing Indigenous Employment,

Response, The Centre for Independent Studies, 2023, <https://www.cis.org.au/wp-

Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, ANU College of Arts & Social Sciences, CAEPR Topical

content/uploads/2023/06/AP49-covid-burden.pdf>

Issue No. 1/2014, <https://caepr.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/Topical_Issue_01-

2014_GrayHunterBiddle_EconomicSocialBenefitsIndigenousEmployment_0.pdf>

12. I. Mooi-Reci, M. Wooden, and M. Curry,

Does Having Jobless Parents Damage a Child’s Future?,

Melbourne Institute, No. 04/19, 2019,

9. S. Lamb and S. Huo,

Counting the Costs of Lost Opportunity in Australian Education, Mitchell Institute

<https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/3232868/ri2019n04.pdf>

report, No. 02/2017, 2017, <https://content.vu.edu.au/sites/default/files/media/counting-the-costs-of-

lost-opportunity-in-aus-education-mitchell-institute.pdf.>

13. As above

10. I. Mohanty, R. Tanton, Y. Vidyattama, and L. Thurecht,

Estimating the Fiscal Costs of Long-term Jobless

14. E. Melhuish and J. Gardiner,

The Impact of Non-Economic and Economic Disadvantage in Pre-School

Families in Australia, Australian Journal of Social Issues, vol. 51, no. 1, 2016,

Children in England, NESTA, 2024, <https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/the-impact-of-non-economic-and-

<https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2016.tb00366.x?saml_referrer.>

economic-disadvantage-in-pre-school-children-in-england/.>

11. The South Australian Centre for Economic Studies,

Disability Employment Landscape Research Report

Agency under FOI

(report commissioned by Disability and Carer Reform Branch Department of Social Services, Precincts and

Page 16 – Detailed findings: the value associated with employment outcomes

Regions), December 2021, <https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/12_2021/disability-

1. Elizabeth Doery, Lata Satyen, Yin Paradies, Graham Gee, and John W. Toumbourou,

Impact of community-

employment-landscape-research-report.pdf.>

based employment on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wellbeing, aspirations, and resilience, BMC

Australians

Public Health, 2024, <https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-024-17909-

Page 19 – Approach: modelling quantifiable benefits

z>

1. Frijters, P and Krekel, C,

A Handbook for Wellbeing Policy-Making: History, Theory, Measurement,

2. M. Gray, B. Hunter, and N. Biddle

, The Economic and Social Benefits of Increasing Indigenous Employment,

Implementation and Examples, Oxford University Press, 2021, <https://academic.oup.com/book/39348>

Indigenous

Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, ANU College of Arts & Social Sciences, CAEPR Topical

Issue No. 1/2014, <https://caepr.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/Topical_Issue_01-

2. Foster, G,

COVID’s Cohort of Losers: The Intergenerational Burden of the Government’s Coronavirus

2014_GrayHunterBiddle_EconomicSocialBenefitsIndigenousEmployment_0.pdf>

Response, The Centre for Independent Studies, 2023, <https://www.cis.org.au/wp-

content/uploads/2023/06/AP49-covid-burden.pdf>

3. Gabrielle Penrose and Gianni La Cava,

Job Loss, Subjective Expectations and Household Spending, Reserve

Bank of Australia, August 2021, <https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2021/2021-

3. Deloitte Access Economics (2017), updated to 2024 dollar terms; analysis of ABS and HILDA data,

by the National

08/full.html#section-how-does-unemployment-affect-household-spending>

budgetary statements on government investment in public services.

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

36

FOI/2425/085

Released

References

Document 1

Page 21 - Detailed findings: modelling and program outcome results

Page 28 – Appendix A: Data tool assumptions and guidance (1/4)

1. The Senate,

Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Annual reports (No. 1 of 2020),

1. Services Australia,

JobSeeker Payment, 2024, <https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/how-much-jobseeker-

<https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/publications/tabledpapers/d876a0a3-019b-480c-aa38-

payment-you-can-get?context=51411>

45aef7025140/upload_pdf/education%20-

2. Services Australia,

Remote Area Allowance, 2024, <https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/how-much-

%20annual%20report.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22publications/tabledpapers/d876a0a3-

remote-area-allowance-you-can-get?context=22571#a2>

019b-480c-aa38-45aef7025140%22>

Page 29 - Appendix A: Data tool assumptions and guidance (2/4)

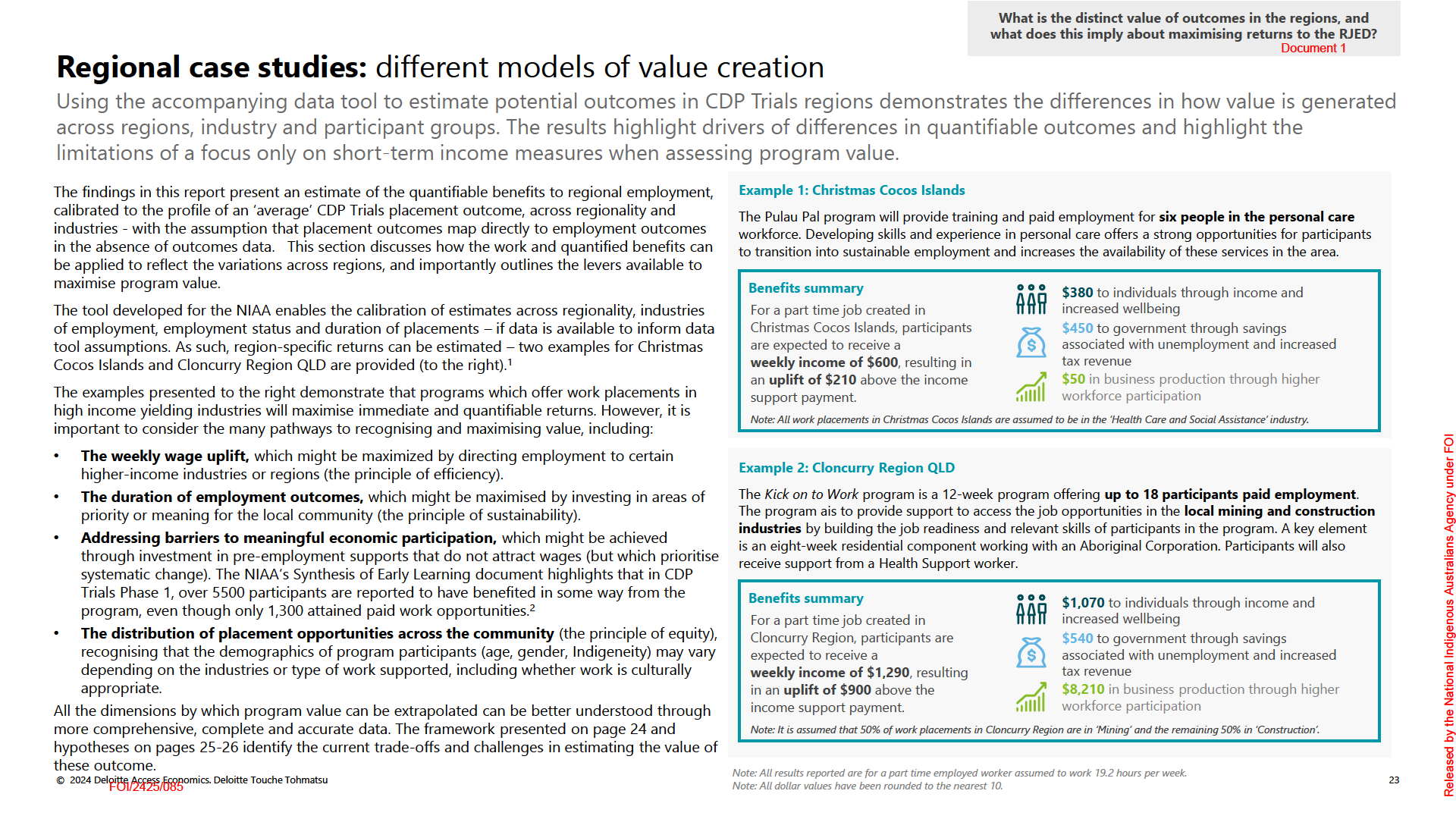

Page 23 – Regional case studies

1. Senate Standing Committee on Education and Employment, Questions on Notice, Supplementary Budget

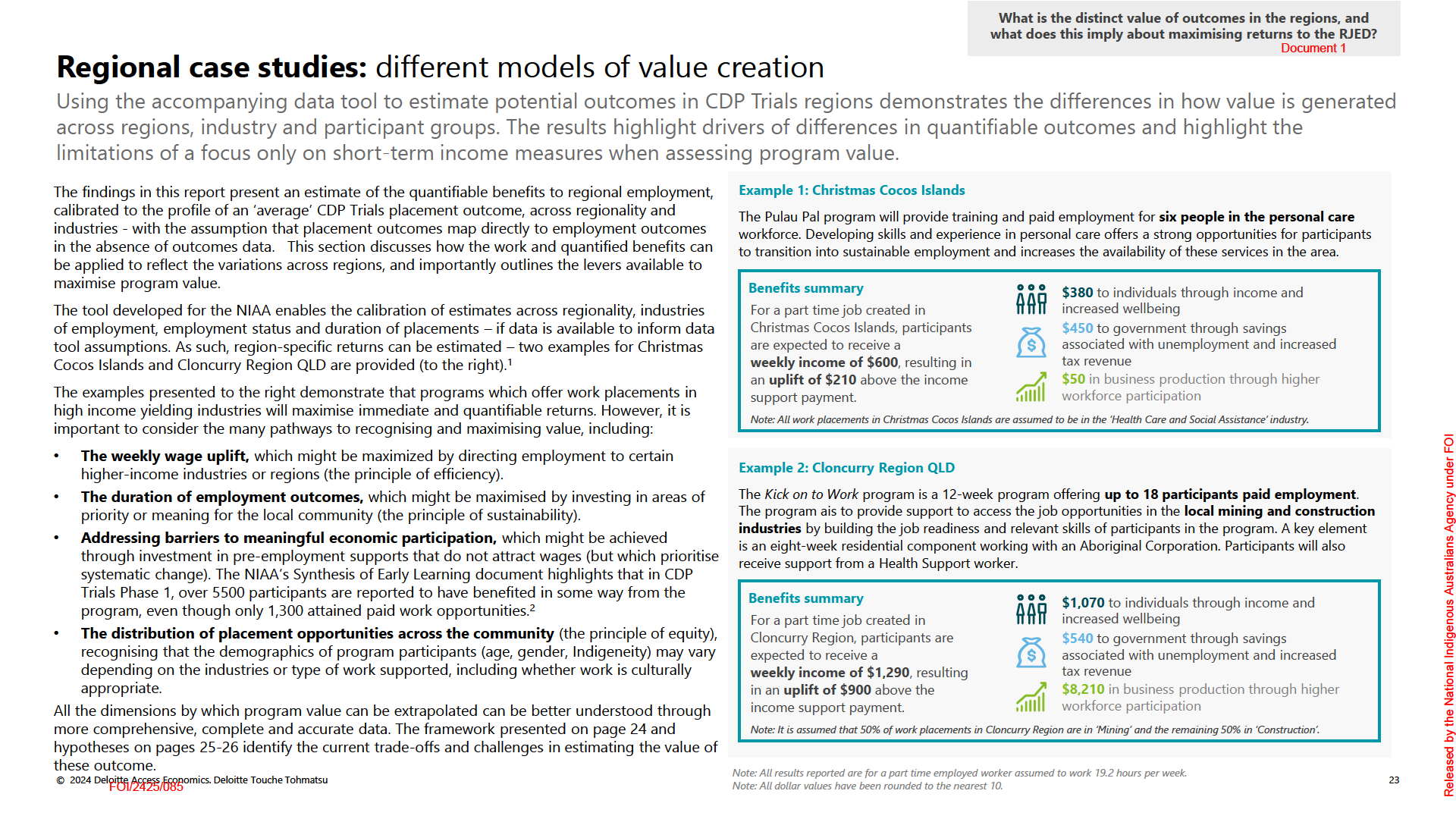

1. The regional case studies presented on this page make assumptions about the number of placements

Estimates 2019-2020: Dept of Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business Question No. EMSQ19-

across industries using descriptions provided in the NIAA’s summary of approved hase 1 trials and are

001227, 2020

designed to be illustrative only. Actual data are used for the Region 9 case study on page 25.

National Indigenous Australian Agency,

Community Development Program: Trialling Pathways to Real

Jobs - Summary of Approved Trials (March 2023)

Page 30 – Appendix A: Data tool assumptions and guidance (3/4):

<https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/publications/cdp-trialling-pathways-summary-

1. Australian Bureau of Statistics,

Australian National Accounts: Input-Output Tables, 2021

approved-trials-mar-2023.pdf>

<https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/national-accounts/australian-national-accounts-input-

2. National Indigenous Australians Agency,

Community Development Program: Phase 1 Trials Synthesis of

output-tables/latest-release>

Early Learnings from ‘Trialling Pathways to Real Jobs’ (April 2024)

2. As above

<https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2024-04/cdp-synthesis-of-early-learnings-

3. Deloitte Access Economics (2017), updated to 2024 dollar terms; analysis of ABS and HILDA data,

tprj.pdf>

budgetary statements on government investment in public services.

Page 25 – Provisional conclusions and their implications

Page 31 - Appendix A: Data tool assumptions and guidance (4/4):

1. The Senate,

Education and Employment Legislation Committee, Annual reports (No. 1 of 2020),

Agency under FOI

1. Frijters, P and Krekel, C,

A Handbook for Wellbeing Policy-Making: History, Theory, Measurement,

<https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/publications/tabledpapers/d876a0a3-019b-480c-aa38-

Implementation and Examples, Oxford University Press, 2021, <https://academic.oup.com/book/39348>

45aef7025140/upload_pdf/education%20-

%20annual%20report.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22publications/tabledpapers/d876a0a3-

2. Foster, G,

COVID’s Cohort of Losers: The Intergenerational Burden of the Government’s Coronavirus

019b-480c-aa38-45aef7025140%22>

Response, The Centre for Independent Studies, 2023, <https://www.cis.org.au/wp-

Australians

content/uploads/2023/06/AP49-covid-burden.pdf>

2. Department of Employment and Workplace Relations

, Employment Pathway Fund Evaluation: Chapter 2 -

Wage Subsidies, FOI Reference D21/527691, 5 April 2023, <https://www.dewr.gov.au/employment-

3. Australian Taxation Office (ATO),

Tax rates – Australian resident 2023-24, 2024,

services-evaluations/resources/employment-pathway-fund-evaluation-chapter-2-wage-subsidies>

<https://www.ato.gov.au/tax-rates-and-codes/tax-rates-australian-residents>

Indigenous

3. Beale, G,

Economic Complexity of Australian States, 2023,

<https://blogs.flinders.edu.au/aiti/2023/10/11/economic-complexity-australian-states/>

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

37

FOI/2425/085

Released

Document 1

General use restriction

This report is prepared solely for the internal use of National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA). This report is not intended to and should not be used or relied upon

by anyone else and we accept no duty of care to any other person or entity. The report has been prepared for the purpose of set out in our work order. You should not

refer to or use our name or the advice for any other purpose.

Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu imited (“DTT ”), its global network of member firms, and their related entities (collectively, the “Deloitte

organization”). DTT (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) and each of its member firms and related entities are legally separate and independent entities, which cannot

obligate or bind each other in respect of third parties. DTTL and each DTTL member firm and related entity is liable only for its own acts and omissions, and not those of

each other. DTTL does not provide services to clients. Please see www.deloitte.com/about to learn more.

Agency under FOI

Deloitte Asia Pacific Limited is a company limited by guarantee and a member firm of DTTL. Members of Deloitte Asia Pacific Limited and their related entities, each of

which is a separate and independent legal entity, provide services from more than 100 cities across the region, including Auckland, Bangkok, Beijing, Bengaluru, Hanoi,

Hong Kong, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, Manila, Melbourne, Mumbai, New Delhi, Osaka, Seoul, Shanghai, Singapore, Sydney, Taipei and Tokyo.

Australians

This communication contains general information only, and none of DTTL, its global network of member firms or their related entities is, by means of this communication,

rendering professional advice or services. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your finances or your business, you should consult a qualified

professional adviser.

Indigenous

No representations, warranties or undertakings (express or implied) are given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information in this communication, and none of

DTTL, its member firms, related entities, employees or agents shall be liable or responsible for any loss or damage whatsoever arising directly or indirectly in connection

with any person relying on this communication.

by the National

© 2024 Deloitte Access Economics. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu

CONFIDENTIAL

FOI/2425/085

Released