Independent Review of the place of Art

and Music Therapy within Australia’s

National Disability Insurance Scheme

Stephen Duckett AM

April 2025

Issues in this report

Ensuring art and music therapeutic

supports are evidence based

Benefits participants because support

Benefits community because public money

more likely to have an impact

well spent

Make sure everyone who bills as an art or

Need to ensure information about evidence

music therapist is an art or music therapist

is easily accessible

Participants and their advisers

Need to make sure smaller participant

need to know about the evidence

communities are not unfairly excluded

to support participant choices

because of poor evidence base

Need to collect and collate data about

Researchers may not have

outcomes for individual participants to help

developed evidence as it

build the evidence

applies to some communities

Key findings and recommendations

• The key finding of this Review is that the literature provides evidence that art and

music therapy are effective and beneficial to people in some circumstances, for

example where the person has a specific condition and where the therapy is

relevant to their seeking to achieve a specific objective or outcome (paragraph 160).

• Art or music therapy should only be included as a funded therapeutic support in a

participant’s plan if there is generalisable evidence which shows the value of art or

music therapy for similar people with these types of goals and these types of

conditions. It is the responsibility of the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA)

to ensure information about the evidence is widely available (paragraph 82).

On evidence

I recommend that the NDIS Evidence Advisory Committee, when established:

• include an assessment of the evidence base for art and music therapy interventions

in specific cohorts in its 2025-26 work plan (paragraph 162).

• considers the concept of a minimal clinically important difference in making its

recommendations (paragraph 142).

• develop explicit processes for making decisions about provision of therapeutic

support in populations where there is a poorly developed evidence base (paragraph

168).

I recommend that the NDIA:

• consider ways in which better information can be provided to participants to assist

them make informed choices about whether particular therapeutic supports could be

a useful, evidence-based addition to their plans (paragraph 104).

• in messaging about evidence, should emphasise the benefits to a cohort of

participants receiving an art or music therapy intervention, distinguishing that from

generic advice about any intervention provided by art or music therapists (paragraph

161).

• strengthen its oversight of plans to ensure that all therapeutic support approved, -

not only in art or music therapy - has a robust evidence base (paragraph 173).

• systematise its collection of data from providers about the effectiveness and

outcomes of therapy interventions for participants, including development of

consistent definitions of interventions aligned to a robust participant outcomes

framework (paragraph 181).

• ensure that data collected by the NDIA is collated and analysed to ensure that the

therapeutic support provided actual y achieves a result for the condition for this

participant with this provider (paragraph 173).

On payments and payment rates

I recommend that the NDIA:

• set rate maxima for art and music therapists on the basis that these are distinct

professions, providing evidence-based therapy, not simply supervising art or music

activities (paragraph 214).

• align the maximum payment limit for art and music therapy with the maximum

payment limit for counsel ors (paragraph 242).

• explore establishing differentials within the allied health professionals’ scales to

recognise different capacity to provide services and/or to recognise levels of skil s

and experience (paragraph 248).

• expand its capacity to monitor market dynamics to assess supply of, and the

demand for, art and music therapy and therapists (paragraph 229).

• In the medium term, set payment limits for art and music therapy that take account

of their labour market monitoring and the need to ensure there is an adequate

supply of art and music therapists to meet the requirement for evidence-based

provision of art and music therapy (paragraph 235).

• consider alternative methods for funding early intervention services which are

consistent with best practice guidelines and any future agreed early childhood

intervention best practice frameworks, which encourage holistic evidence-based and

outcomes-focused provision consistent with the early childhood approach

(paragraph 54).

• consider a different payment and funding approach, particularly for large

organisational providers (paragraph 270).

• specify in its Pricing Arrangements and Price Limits, that art and music therapy

cannot be claimed under ‘other professional’ (paragraph 243).

• ensure that funding for art and music therapy as a Therapeutic Support for self-

managed participants be limited to supports provided by appropriately trained art

and music therapists as defined by NDIA who meet the requirements of NDIS

Quality and Safety Commission registration. In other circumstances, art or music

activities should be classified as Participation in Community, Social and Civic

Activities and funded accordingly (paragraph 251).

• enhance its invoice verification process to ensure that only eligible providers are

reimbursed under the art or music therapy item numbers (paragraph 34).

I recommend that the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission

• consider introducing an ongoing mechanism to review the verification requirements

for recognition as an art or music therapist (paragraph 67).

link to page 6 link to page 10 link to page 13 link to page 17 link to page 41 link to page 57

Table of Contents

Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1

What are art and music therapy? .........................................................................................

5

Early intervention services ..................................................................................................

8

The evidence bases for art and music therapy ....................................................................

12

Pricing and rate setting .....................................................................................................

36

Conclusion ......................................................................................................................

52

link to page 6 link to page 6

Introduction

1. The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) is one of the most important reforms in

social policy in Australia in recent decades

.1 It was developed so that people with

disabilities are able to participate in Australian society and be provided with the supports

necessary to achieve that.

2. The NDIS was set up to support people with ongoing disabilities (including younger

people who would benefit from early intervention).

3. The NDIS arose because of historic – and, unfortunately, continuing – barriers to

inclusion as noted in a submission to this review:

The NDIS as a support scheme is not needed solely because people have

impairments. It exists equal y as an indictment on the chronic inaccessibility of nearly

all mainstream spaces and services. It costs a lot of money to include Australians

with disability because of serious deficiencies in the skil s, knowledge and flexibility of

our public services, infrastructures and population. You cannot capacity build

disabled individuals out of the barriers they experience when many of those barriers

are the result of environmental conditions, not only individual on

es.2

4. The premise of the NDIS is facilitative, contributing to participants’ achieving their own

goals, with both goals and supports articulated in their individual plans. Plans may also

include goals and supports which are not provided by the NDIS but are the result of

participants’ own choices, and broader community services.

5. The supports which can be funded through the NDIS are specified (‘NDIS Supports’) and

are distinct from ordinary costs of living. Approved NDIS supports include ‘Therapeutic

supports’ defined as

Supports that provide evidence-based therapy to help participants improve or

maintain their functional capacity in areas such as language and communication,

personal care, mobility and movement, interpersonal interactions, functioning

(including psychosocial functioning) and community living.

6. To date art and music therapy have been included as therapeutic supports, but a recent

policy change - since paused – called these services into question, which was in part a

stimulus for this Review.

1 Buckmaster, Luke and Clark, Shannon (2018), 'The National Disability Insurance Scheme: a chronology',

Research Paper (Canberra: Parliament of Australia. Department of Parliamentary Services); Miller, Pavla

and Hayward, David (2016), 'Social policy ‘generosity’ at a time of fiscal austerity: The strange case of

Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme',

Critical Social Policy, 37 (1), 128-47.

2 Deafblind Australia Submission to Independent Review of NDIS Art and Music Therapy Supports

1

link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 7

7. The policy change was made in the context of a ‘rapid revi

ew’3 of the evidence about the

effectiveness of art and music therap

y.4 Rapid reviews are legitimate and a well-

accepted method of research synthesis and have been described as ‘a pragmatic

approach to synthesize evidence in a timely manner.

’5

8. I was asked by the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA), which administers the

NDIS, to review two aspects of art and music therapy within the NDIS:

• the NDIA’s ‘review of evidence’, which found that there is limited evidence about

the effectiveness of art and music therapy as evidence-based, therapeutic

supports for most people with disability; and

• the pricing of music and art therapy compared with other allied health therapies.

9. This Report then is about the triad of participants, evidence, and the therapies/therapists,

and how they interact in the interests of the community, especially participants.

10. Australia has a strong history of ensuring that publicly funded services and supports are

evidence-based, starting with the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme more than thirty

years ago

,6 and later extending to the Medicare Benefits Schedule. This approach is

being extended to the NDIS and so, in the medium term, identifying whether particular

interventions work for specific cohorts wil be the responsibility of a new Evidence

Advisory Committee in the Department of Social Services, as recommended by the NDIS

Revi

ew.7 The new committee wil draw on evidence about the benefits, quality, safety

and cost-effectiveness of NDIS supports.

11. As part of this review, I invited submissions and received over 600 responses from key

provider associations, Disability Representative and Carer Organisations, individual

participants receiving these services (and their families/carers/advocates), and service

providers.

3 Hamel, Candyce, et al. (2021), 'Defining Rapid Reviews: a systematic scoping review and thematic

analysis of definitions and defining characteristics of rapid reviews',

Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 129,

74-85.

4 National Disability Insurance Agency. Evidence and Practice Leadership Branch (2024), 'Evidence

Summary: Art and music therapy', (Canberra: NDIA); https://dataresearch.ndis.gov.au/research-and-

evaluation/decision-making-access-and-planning/evidence-summary-art-and-music-

therapy#download-the-evidence-summary

5 Devane, Declan, et al. (2024), 'Key concepts in rapid reviews: an overview',

Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology, 175, 111518.

6 Lopert, Ruth and Viney, Rosalie (2014), 'Revolution then evolution: The advance of health economic

evaluation in Australia',

Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen, 108 (7),

360-66.

7 Independent Review into the National Disability Insurance Scheme (2023), 'Final Report: Working

together to deliver the NDIS', (Canberra: The Review).

2

link to page 8

12. Over a fifth of all submissions were from people who identified themselves as

participants or carers. I would like to thank those participants who shared their personal

stories and acknowledge the contributions they are making to improving the NDIS.

13. I also met with the three key associations representing providers of art and music

therapy: the Australian Music Therapy Association, the Australian, New Zealand and

Asian Creative Arts Therapies Association and the College of Creative and Experiential

Therapies of the Psychotherapy and Counsel ing Federation of Australia. I had separate

consultations with NDIS participants.

14. The NDIA provided me with data to help me understand the dimensions of the provision

of art and music therapy and their review of evidence

.8

15. I would like to thank all who made submissions and those who participated in

consultations, and staff at the NDIS who helped me in analysing submissions and

providing data.

Positionality and qualifications

16. My office is on the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri peoples of the Kulin Nation. I

acknowledge my debt to First Nations Australians and pay my respects to Elders past

and present. I acknowledge that First Nations Australians continue to suffer

disadvantage in their access to, and outcomes from, health and disability services. There

is a paucity of evidence about therapeutic supports for First Nations Australians, and I

regret that this review is not able to make targeted evidence-based recommendations

which might improve access or outcomes for First Nations Australians.

17. I am a white male and no one in my immediate family participates in the NDIS. I have

attempted to address my positionality by reading carefully all the submissions to this

review and listening to the experiences of people with disability as presented to the

review.

18. I bring to this Independent Review internationally recognised expertise in pricing of public

services, particularly health care, a deep understanding of the way governments and

public services operate, a history of management and policy achievements, and a

lifelong commitment to equity, efficiency, and quality of service provision.

8 National Disability Insurance Agency. Evidence and Practice Leadership Branch (2024), 'Evidence

Summary: Art and music therapy', (Canberra: NDIA).

3

link to page 9 link to page 9

19. My prior experience with disability services and the NDIS has been partly through

employment and board roles. In the Victorian Department of Health and Community

Services in the early 1990s I had line responsibility for two rural regions at different times

and so had responsibility for all Departmental services in the regions, including disability

services. As Secretary of the Commonwealth Department of Human Services and

Health, also in the 1990s, I had responsibility for aspects of disability services. I am also

a former board member of the Brotherhood of St Laurence, which provided local area

coordination and early intervention advice under contract to the NDIA. When I was Dean

of Health Sciences at La Trobe University, the Faculty included education for art therapy.

20. I have maintained a general interest in aspects of disability policy and services and have

co-authored a number of publications on aspects of measurement relating to disability

and therapy supports

.9 I also included a review of disability services in my book on the

Australian health care system

.10

9 Dyson, M., Allen, F.C.L., and Duckett, S.J. (2000), 'Profiling childhood disability: The reliability of the

educational needs questionnaire',

Evaluation and Program Planning, 23 (2), 177-85; Dyson, M., Duckett,

S.J., and Allen, F.C.L. (2000), 'A therapy-relevant casemix classification system for school age children

with disabilities',

Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 81 (May), 634-43; Morris, M., et al.

(2005), 'Reliability of the Australian Therapy Outcome Measures for quantifying disability and health',

International Journal of Therapy & Rehabilitation, 12 (8), 340-46; Perry, Angela, et al. (2004), 'Therapy

outcome measures for allied health practitioners in Australia: the AusTOMs',

International Journal of

Quality in Health Care, 16 (4), 285-91; Unsworth, Carolyn A., et al. (2004), 'Validity of the AusTOM scales:

A comparison of the AusTOMs and EuroQol-5D',

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2 (64), 1-12.

10 Duckett, Stephen (2022),

The Australian Health Care System (6th ed.) (Melbourne: Oxford University

Press).

4

link to page 10 link to page 10

What are art and music therapy?

21. Art and music therapy are increasingly recognised as important potential contributors to

improving the life situation for people across a broad range of condition

s.11

22. The Australian, New Zealand and Asian Creative Arts Therapies Association

(ANZACATA) describes art therapy as the use of ‘art, media and the creative process

(drawing, writing, sculpting, drama, clay, sand, dance and movement) to facilitate the

exploration of feelings, improve self-awareness and reduce anxiety for clients.’

23. Art therapists are not registered as part of Australia’s national system of registering

health professionals. However, to provide therapeutic supports funded by the NDIS an

art therapist must, among other things, be a ‘professional member’ of ANZACATA.

24. Professional members of ANZACATA are required to have a master’s degree in art

therapy approved by ANZACATA.

25. The Australian Music Therapy Association (AMTA) defines music therapy as ‘the

intentional and therapeutic use of music by registered music therapists (RMTs) to

support people to improve their health, functioning and wel being’. Aalbers et al.

identified two types of music therapy: ‘active (where people sing or play music) and

receptive (where people listen to music)

’.12

26. Music therapists are also not registered as part of Australia’s national system of

registering health professionals, but AMTA is a member of the National Al iance of Self-

Regulating Health Professions.

27. To be a registered music therapist endorsed by AMTA, a person must complete a

master’s degree course approved by AMTA. To provide therapeutic supports funded by

the NDIS a music therapist must, among other things, be a ‘registered music therapist’

with AMTA.

11 World Health Organization. Regional Office for, Europe (2023), 'WHO expert meeting on prevention and

control of noncommunicable diseases: learning from the arts. Opera House Budapest, Hungary, 15–16

December 2022: meeting report', (Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe).

12 Aalbers, Sonja, et al. (2017), 'Music therapy for depression',

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11, CD004517. Davies and Clift make the same distinction about types of arts engagement: Davies,

Christina R. and Clift, Stephen (2022), 'Arts and Health Glossary - A Summary of Definitions for Use in

Research, Policy and Practice',

Frontiers in Psychology, 13 (949685), 1-6.

5

link to page 11 link to page 11

28. A consequence of neither art nor music therapy being nationally registered professions is

that there is no protection of those titles, so anybody can call themselves an ‘art

therapist’ or a ‘music therapist’. However, as indicated above, the NDIS rules prescribe

who ought to be able to claim the relevant item numbers.

29. In 2023-24 about 13,400 people were supported by the NDIS for one of these services,

and 600 who received both.

Table 1: Number of art and music therapy participants and providers, 2023-24

Art therapy

Music therapy

Number of participants

6,788

7,217

Number of providers

1,672

1,405

Total payments

$ 13.4m

$ 16.3m

Source: NDIA administrative data provided to this review; Note: Data in this table (and in

subsequent tables and figures) may not include full information about supports provided to

self-managed participants.

30. There is some evidence that people receiving music therapy tend to be younger than

those receiving art therapy. About one in five people receiving music therapy are under

9, compared to one in seven receiving art therapy (21% v 14%). Conversely, about 37%

of those receiving art therapy are 35 or over compared to 30% of those receiving music

therapy. However, the NDIS data does not allow for the identification of usage of art and

music therapy for under 7s as those services are claimed under a general therapy code.

31. Again, subject to the issue about under 7s above, about two thirds of people who receive

art therapy are women or girls. The gender balance is reversed for music therapy: 40%

of people who receive music therapy are women or girls

.13

32. The number of separate art or music therapy providers paid under the NDIS appears to

be larger than the membership base of the relevant associatio

ns.14

33. Art or music

therapy are not the same as art or music

activities:

•

Art or music therapy: Supports that formally implement elements of art or music

as therapeutic techniques alongside or instead of psychotherapy, physiotherapy,

speech therapy and rehabilitation. To be considered art or music therapy, a

service must meet all the following criteria: Art or music therapy is delivered by a

13 I was not provided with data on the number of non-binary participants.

14 The data on number of providers is based on number of unique ABN codes. It is possible that a therapist

may bill using two or more ABNs, for example, to distinguish sites of care.

6

qualified art or music therapist (typically prepared at master’s level); implements

a clearly defined and scientifically valid mechanism of action; and aims at an

identified and measurable outcome beyond leisure, such as psychosocial

functioning, physical capacity or communication.

•

Art or music activities: Services that involve art or music but do not meet al of the

criteria of art or music therapy, even if delivered by a qualified art or music

therapist or involve therapeutic techniques. These are mainly aimed at leisure or

use art or music to facilitate other benefits such as social interactions or

movement.

34.

I recommend that the NDIA enhance its invoice verification process to ensure that

only eligible providers are reimbursed under the art or music therapy item

numbers.

7

link to page 13 link to page 13

Early intervention services

35. There are two pathways into the NDIS – early intervention for younger people and the

general permanent disability stream. Most of what I have to say in this report relates to

the larger element of the NDIS, permanent disability and supports for this group of

participants.

36. The purpose of early intervention is to mitigate the impact of a person's impairment upon

their long-term functional capacity by providing support at the earliest possible stage.

Early intervention support is also intended to benefit a person by reducing their future

need for supports and by strengthening the sustainability of their informal supports, e.g.

building the capacity of their carer(s)

.15

37. A draft National Best Practice Framework for the provision of early childhood

intervention, drawing on an extensive literature review and a review of best practice, is

currently being developed

.16 A major theme of the best practice framework for early

intervention is the importance of being child-and family-centred and outcomes-focused.

38. The draft Framework applies across all areas of early childhood intervention and so is

not NDIS-specific. If the Framework is seen as relevant and useful by stakeholders,

there would be merit in its being used to shape NDIS provision.

39. Best practice early childhood intervention identifies the desired outcomes and then the

most effective interventions consistent with the principles that underpin the framework.

The key questions are: What are the likely gains in function and meaningful participation

in everyday settings of childhood? Are the gains greater than alternative interventions or

are the gains sufficiently effective in combination with other interventions so as to be

attractive? If the therapy is used but does not lead to improved functioning and

meaningful participation in the child, it should not continue to be used.

40. In terms of my commission, to examine the evidence base for art and music therapy, the

review of best practice points to how art and music therapy ought to be provided as part

of early childhood intervention services, namely in the context of implementation of this

(draft) evidence-based National Best Practice Framework.

15 Imms, Christine, et al. (2024), 'Review of best practice in early childhood intervention: Desktop review

full report.' (Melbourne: The University of Melbourne).

16 The Framework is being developed by a broad group including a number of stakeholders. It was

commissioned by the Department of Social Services. The University of Melbourne (2025), 'Review of best

practice in early childhood intervention: Draft Practice Framework v2.0', (Melbourne: The University of

Melbourne).

8

link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14

41. However, there are elements of the overall funding design of the NDIS which may

militate against the implementation of the themes of the (draft) National Best Practice

Framework.

42. The current funding arrangements for provision of paediatric speech and language were

reported in a recent study as not consistent with the evidence, although the relevant

papers did not explore the nature of the inconsistency, nor point to specific directions for

reform

.17

43. A small qualitative study conducted in the early stages of the implementation of the

NDIS, identified several themes about its then negative impact on early childhood

intervention services. It identified that sometimes the parents felt disempowered

compared to previous systems and emphasised the importance of good information for

families

.18 It also concluded that the NDIS funding arrangements – essential y fee-for-

service – may have inhibited good service provision.

44. Use of a ‘key worker’ to coordinate services may address some of the problems

identified with early childhood intervention service

s,19 however, involvement of a key

worker is not universal.

45. This Review cannot address all of the issues involved in the development of early

childhood intervention policy. However, my observation is that the atomised approach,

based on separate funding for separate therapeutic supports is not conducive to

encourage the policy directions set out in the draft National Best Practice Framework,

and hence does not facilitate evidence-based provision in this context.

46. In the health sector there is increasing recognition of the importance of multidisciplinary

teams in the provision of health care, especially for older people. The same is true for

early intervention for all people with disability. In the health sector, the response is to

recognise the limitations of fee-for-service payments and to encourage holistic payments

which encourage continuity of care and the right mix of services being provided to the

person in need

.20

17 Nickless, Tristan, et al. (2023), 'Public purse, private service: The perceptions of public funding models

of Australian independent speech-language pathologists',

International Journal of Speech-Language

Pathology, 25 (3), 462-78; Nickless, Tristan, et al. (2024), 'Aligned or misaligned: Are public funding

models for speech-language pathology reflecting recommended evidence? An exploratory survey of

Australian speech-language pathologists',

Health Policy OPEN, 6, 100117.

18 Gavidia-Payne, Susana (2020), 'Implementation of Australia's National Disability Insurance Scheme:

Experiences of Families of Young Children with Disabilities',

Infants & Young Children, 33 (3), 184-94.

19 Young, Dana, et al. (2021), 'Understanding key worker experiences at an Australian Early Childhood

Intervention Service',

Health & Social Care in the Community, 29 (6), e269-e78.

20 Strengthening Medicare Taskforce (2023), 'Report', (Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care).

9

link to page 15 link to page 15

47. The same principles might apply for early intervention services. Here one might see

payment for a multidisciplinary team, with the expectation that the multidisciplinary team

provides holistic support to achieve agreed outcomes for a specified number of people in

the early intervention stream for a defined time. e.g., a year. People should have the right

to change providers to ensure appropriate accountability and responsiveness with a

specified notice period.

48. Such a holistic approach might be more difficult to organise in rural and remote Australia,

where the numbers involved are small, but it might be possible to link up with local

community services who are able to provide support, especially with remote guidance to

those teams provided virtual y. This was recommended by the NDIS Review

.21

49. Provision of early childhood intervention services in this model might also be through a

procurement approach, where potential providers respond to an open invitation to

participate based on their capabilities and ability to provide services consistent with the

National Best Practice Framework when finalised and as updated from time to time.

50. It is important to note that the draft National Best Practice Framework is just that, a draft.

It has not yet been adopted as policy and may not be. But if it is adopted, then it is

important that funding and policy aspirations are aligned, lest the Framework simply be

another statement of unimplemented aspirations.

51. Funding of multi-disciplinary teams is not simple valorising use of a ‘multi-disciplinary

team’ item. It is about facilitating a service which involves true teamwork, on an ongoing

basis, in the interest of the participant, with appropriate accountabilities

.22

52. What I am pointing to here is not a return to block funding, which was associated with a

lack of accountability to clients, but rather that existing fee-for-service funding

arrangements do not serve participants well and may stymie implementation of a new

National Best Practice Framework if adopted.

53. In this model, perhaps termed ‘team funding’, participants would be empowered by being

able to move between teams/providers if their needs were not being met. Under this

arrangement the NDIA would augment its existing oversight by monitoring participant

reported experience measures, and tracking outcomes.

54.

I recommend that the NDIA consider alternative methods for funding early

intervention services which are consistent with best practice guidelines and any

21 Independent Review into the National Disability Insurance Scheme (2023), 'Final Report: Working

together to deliver the NDIS', (Canberra: The Review).

22 Katzenbach, Jon R and Smith, Douglas K (2005), 'The discipline of teams',

Harvard business review, 83

(7/8), 162-71.

10

link to page 16

future agreed early childhood intervention best practice frameworks, which

encourage holistic evidence-based and outcomes-focused provision consistent

with the early childhood approach. In the interim, the NDIA should continue to fund

early childhood intervention supports in a flexible budget which promotes a best practice

approach consistent with best practice guidelines in early childhood intervention

.

55. As part of foundational supports, states might give consideration to professional

development for teachers and early childhood educators to work with music and art

therapists to build their capability and confidence in provision of programs which draw on

art or music therapy evidence

.23

56. Unless otherwise specified, the remainder of this report does not consider the evidence

base for, or pricing of, early intervention services for children or other groups.

23 Ng, Siu-Ping, et al. (2024), 'Impact of online professional development on Hong Kong kindergarten

teachers' confidence: An experimental study',

Australian Journal of Music Education, 56 (2), 52-64.

11

The evidence bases for art and music therapy

57. A number of stakeholders, including the three main provider associations provided

comprehensive submissions highlighting the evidence base for art or music therapy. As

discussed below, I received more than 150 submissions from participants and/or carers,

many of them recounting their personal experience of the benefits of art or music

therapy. Some of these also pointed to relevant literature for me to consider.

AMTA submission

58. AMTA provided a comprehensive submission (including appendices directing me to

relevant studies). AMTA identified from the literature a number of areas where music

therapy might be of benefit:

•

Functioning (including psychosocial functioning): Here AMTA concluded that ‘A

range of music therapy methods, techniques and interventions are examined in

the research literature, including therapeutic singing and instrument play,

rhythmic cueing, music assisted storytelling, dyadic improvisations, receptive

methods, therapeutic song writing and composition, music and movement, and

musical play. Research evidence shows a range of outcomes relevant to this

domain across various focus areas that relate to functioning, including global

cognition, attention, memory, recal , auditory discrimination, music engagement,

depression, anxiety, mood, and apathy’;

•

Language and communication: AMTA noted that ‘Music therapy evidence

demonstrates improvements in a range of functional language and

communication domains. Improvements for people who wil be able to develop or

recover language are obviously more amenable to quantitative measurement.

This is seen by significant improvements in people with aphasia after music

therapy as demonstrated through meta-analysis;

•

Interpersonal Interactions: AMTA identified that in this field ‘participants with

primary impairments of either neurological or psychosocial types are the most

common (18 and 16 citations respectively), and research with children and

adolescents is prominent (32 citations). There are 19 systematic reviews or meta-

analyses that are relevant to this area; and

•

Mobility and movement: The AMTA summary showed ‘A total of 26 citations

exploring the role of music therapy in improving movement and mobility functional

capacity have been selected for this summary. These studies explore music

therapy movement interventions for people experiencing impairments in the

NDIA-related domains of neurological functioning (18 citations), physical

functioning (5 citations) and cognitive functioning (3 citations)’.

59. AMTA also noted that music therapy can offer benefits relating to

community living but

the evidence base overlaps other areas.

12

link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 18

60. The AMTA analysis is structured according to functional domains. Within each of these

functional domains, systematic reviews look at specific conditions such as aphasia

.24 The

critical issue for establishing an evidence based is therefore the interaction of the

condition and the functional domain.

ANZACATA submission

61. Although grouped together in this Review, art and music therapy have both similarities

and differences. The definition of music therapy cited above highlights the use of music

as an intervention. In contrast, the definition of art therapy highlights arts as a medium

which allows the intervention which is the exploration of feelings.

62. The ANZACATA submission therefore drew my attention to the evidence base for the

psychological literature as published by the Australian Psychological Society

,25 with the

assumption being that art therapists use the relevant range of psychological

interventions.

63. ANZACATA also provided a survey of the literature relating to art therapy specificall

y.26

64. Again, both the general and specific literature is structured according to the evidence for

specific conditions, with literature for one functional domain – cognition – identified in the

art therapy specific literature review.

PACFA CCET submission

65. The Col ege of Creative and Experiential Therapists of the Psychotherapy and

Counsel ing Federation of Australia (PACFA CCET) also made a submission. The

evidence table of their submission covered much the same ground as AMTA’s and

ANZACATA’s.

66. PACFA CCET also argued that accreditation through their processes should be

recognised under the NDIS arrangements.

67.

I recommend that the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission consider

introducing an ongoing mechanism to review the verification requirements for

recognition as an art or music therapist.

24 Liu, Qingqing, et al. (2022), 'The effect of music therapy on language recovery in patients with aphasia

after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis',

Neurological Sciences, 43 (2), 863-72.

25 Australian Psychological Society (2024), 'Evidence-based psychological interventions in the treatment

of mental disorders: A literature review', (Melbourne: APS).

26 Gray, Deanne (2022), 'The Proven Efficacy of Creative Arts Therapies: What the Literature Tells Us',

(North Brighton: ANZACATA).

13

link to page 19 link to page 19

Disability Representative and Carer Organisations

68. Several Disability Representative and Carer Organisations made helpful submissions to

this review and also provided evidence of the benefit of art or music therapy for

participants with specific condition

s.27

Towards a learning organisation

69. The NDIA should strive to be a learning organisation. This is not just jargon but is a

guiding principle that strives to both improve care provided and contribute to the body of

evidence on which care is based. A learning organisation is ‘an organization skil ed at

creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge, and at modifying its behaviour to reflect

new knowledge and insights’

.28

70. The world around us is changing and new knowledge is being created all the time. It is

critical that NDIS participants benefit from that new knowledge as quickly as possible,

whether it is knowledge about new interventions which have been shown to make a

difference and so need to become available to all participants, or knowledge about old

practices which have been shown not to make a difference and need to be discarded as

giving false hope and costing money.

71. The NDIA should become more adept at gathering data – including data on the

experience of NDIS participants – and using data to inform the plan development and

approval process. It should be at the forefront of synthesising evidence to inform its

decisions and is a theme of this review.

27 e.g., Dementia Australia Independent Review of NDIS art and music therapy supports: A Dementia

Australia Submission

28 Garvin, David A (1993), 'Building a Learning Organization',

Harvard Business Review, 71 (4), 78-91.

14

link to page 20 link to page 20

What is evidence?

72. Section 3.2 of the

National Disability Insurance Scheme (Supports for Participants) Rules

2013 states that

In deciding whether the support wil be, or is likely to be, effective and beneficial for a

participant, having regard to current good practice, the CEO (of the NDIA) is to

consider the available evidence of the effectiveness of the support for others in like

circumstances. That evidence may include:

• published and refereed literature and any consensus of expert opinion;

• the lived experience of the participant or their carers; or

• anything the Agency has learnt through delivery of the NDIS.

73. Further, published NDIS guidance, states that

Therapeutic supports under the NDIS are limited to ‘supports that provide

evidence-

based therapy’ (emphasis added).

74. The NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission has produced an ‘Evidence Informed

Practice Guide’ which portrays evidence informed practice as being shaped by the rights

and perspectives of the person with disabilities; best research and evaluation evidence;

clinical and provider expertise; and information from the implementing or practice

context

.29

75. Schalock defined evidence-based practices as ‘practices for which there is a

demonstrated relation between specific practices and measured outcomes

.’30 I wil return

to the meaning of ‘demonstrated relation’ later.

76. What is critical is how do the different types of knowledge and evidence interact? It is

appropriate to use different types of evidence at different stages of a participant’s plan

development and implementation journey, making the way the NDIS Guidance and the

Schalock definition are phrased somewhat problematic.

77. Firstly, what is regarded as ‘evidence’ needs to be considered from the perspective of

both the system and the individual.

78. In my view, to meet the evidence criterion in the NDIS definition there should be rigorous

studies which show that for this type of client, the support (art or music therapy) achieves

a measurable result. As art and music therapy in Australia is influenced by developments

29 NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission (2023), 'Evidence-Informed Practice Guide', (Penrith, NSW:

The Commission).

30 Schalock, Robert L., et al. (2017), 'Evidence and Evidence-Based Practices: Are We There Yet?',

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 55 (2), 112-19. page 115

15

link to page 21 link to page 21

internationally in these professions, the evidence synthesis of the effectiveness of these

therapies should draw on international replicable evidence.

79. For an individual participant, this approach to the use of evidence is prospective, that is,

as a participant's plan is being developed, there is research evidence available which

shows that art or music therapy has the potential to benefit this individual. This then can

inform the plan for the participant.

80. What is important here is that the evidence being considered is reproducibl

e,31 both in

the sense that another study looking at the same issue wil most likely come to the same

conclusion, but also that given this study, we can presume that this NDIS participant wil

likely benefit from this intervention

.32

81. That is, synthesis of the research evidence wil enable the Department of Social Services

and the NDIA, on the advice of the new NDIS Evidence Advisory Committee, to form a

view about the effectiveness of that intervention for that participant cohort group with

similar goals. There wil always be a judgement here, as the population in research

studies may never mirror exactly the NDIS participant population, but what is critical is

that participants know what is likely to work for them, based on the best available

evidence, and so how their packages should be used. Similarly, sustainability of the

NDIS means that it is important that the NDIA knows what is likely to have a beneficial

effect for participants.

82. Specifically, subject to the caveats discussed later,

art or music therapy should only

be included as a funded therapeutic support in a participant’s plan if there is

generalisable evidence which shows the value of art or music therapy for similar

people with these types of goals and these types of conditions. It is the

responsibility of the NDIA to ensure information about the evidence is widely

available, an issue to which I wil return.

83.

In addition, therapists should monitor a person’s progress in response to the therapy

provided to ensure that,

in this instance, a measurable and meaningful result is being

achieved. That is, if the therapist’s proposed treatment plan is implemented, the literature

wil show (prospectively) that art or music therapy may benefit this individual because of

the experience of providing these supports in the past to others in a similar situation.

What we now need to know retrospectively is whether the support works as provided by

31 Foley, Thomas and Horwitz, Leora I. (2025) Learning Health Systems [online text], Cambridge University

Press, page 6

32 Relatively new UK guidance is useful here: Skivington, Kathryn, et al. (2021), 'A new framework for

developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance',

BMJ, 374, n2061.

16

link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 22

this therapist to

this person in

this context. ‘Result’ here would be outcomes as

contemplated in an individual’s goals and would be different from the person’s previous

situation and trajectory.

84. This type of evidence is retrospective. That is, only after a participant has received

therapeutic supports is it possible to measure the impact of those supports.

85. Although there are common measures of outcomes of provision of therapeutic support,

both covering multiple therapi

es33 and discipline specific, each clinician has autonomy in

determining which measures to use, and how often.

86. Overtime there should be more systematisation of how information on a participant’s

progress and outcomes are collected, collated, and analysed. This wil help build an

evidence base where none exists today and is a key component of building a learning

organisatio

n.34 I wil return to this issue of reporting later.

87. Other types of evidence, such as professional judgement, might also be considered but

that itself must be evidence based, supported by the literature. Again, the clinician or

technical advisor has autonomy to determine what they might recommend as the best art

or music therapy intervention for this person at this time. The clinician or technical

advisor here would draw on their own professional experience and knowledge of the

evidence and their understanding of the participant’s situation and goals.

88. During this review, I received many personal testimonies from people with disabilities,

their carers, or advocates, which attest to the benefit to those individuals of art or music

therapy

.35 Similarly, I received many submissions from therapists who recounted

appropriately anonymised stories about the benefits of the therapy they provided. I also

saw several anonymised professional reports produced by art or music therapists

documenting the progress made while individual participants were receiving these

therapies. Stakeholders also provided me with vignettes showing the benefits of the art

or music therapeutic supports provided to individual participants. There are also

published papers describing case studies of the outcomes of art and music therapy

.36

89. One cannot but be moved by these stories.

33 Perry, Angela, et al. (2004), 'Therapy outcome measures for allied health practitioners in Australia: the

AusTOMs',

International Journal of Quality in Health Care, 16 (4), 285-91.

34 Foley, Thomas and Horwitz, Leora I. (2025)

Learning Health Systems [online text], Cambridge University

Press.

35 I also heard stories where music therapy was not useful, indeed said to be detrimental.

36 Thompson, Grace A. and McFerran, Katrina Skewes (2015), 'Music therapy with young people who have

profound intellectual and developmental disability: Four case studies exploring communication and

engagement within musical interactions',

Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 40 (1), 1-11.

17

link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23

90. I heard firsthand of the difference art or music therapy can make in those individual

circumstances, not only to the person with disabilities but also to those around them.

Unfortunately, support for people with disabilities is stil quite gendered in Australia: in

2022 6.1 per cent of women were primary carers, compared to 3 per cent of men

,37 so

there is a gender equity issue at play here too.

91. The personal statements in submissions and in the consultations address the second

limb of my proposed approach to ‘evidence-based’.

92. That we see change in participants associated with provision of therapeutic supports is

real y no surprise. There is now a substantial – and growi

ng38 - literature, including

systematic reviews, and in the case of music therapy, summaries of

,39 and systematic

reviews of, systematic review

s,40 which outline the benefit of art or music therapy in

specific circumstances, or for people with specific conditions.

93. Although the individual stories shared with me show that there was generally a benefit to

those individuals, they don’t show

in a systematic way whether an alternative support (or

alternative supports) might have provided the same benefit, or whether a different

approach to art or music therapy (e.g. facilitating the carer) might have achieved the

same (or lesser or greater) benefit. Of course, there were some stories which described

how all these other therapies had been tried but no progress was being made until art or

therapy was provided. But it is hard to put these together in a systematic pattern to make

an evaluative assessment.

94. These stories, of prior failure and subsequent progress, raise the question of why art or

music therapy was not provided earlier? If there is evidence that art or music therapy is

beneficial, why was it not part of the original package right from the start?

95. This may not be an issue unique to art or music therapy. But the therapeutic supports

considered in this review are provided by professions which are relatively small

compared to other allied health disciplines, and so the local area coordinator or other

places where participants may gather information, may not be aware of whether these

37 Australian Bureau of Statistics (2024),

Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings

(Canberra: ABS). The data are for people supporting both older people and younger people with

disabilities.

38 Rodriguez Novo, Natalia, et al. (2021), 'Trends in Research on Art Therapy Indexed in the Web of

Science: A Bibliometric Analysis',

Frontiers in Psychology, 12 (752026), 1-10.

39 Kamioka, Hiroharu, et al. (2014), 'Effectiveness of music therapy: a summary of systematic reviews

based on randomized controlled trials of music interventions',

Patient Preference and Adherence, 8 (null),

727-54.

40 Wu, Jiaming, Zhang, Qing, and Wu, Aihong (2024), 'Functioning, health and developmental benefits of

music interventions for children and adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a

systematic review of systematic reviews',

Chinese Journal of Rehabilitation Theory and Practice, 543-53.

18

link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 24

therapeutic supports might make a difference in these cases, or even of the existence of

these therapeutic supports at all.

96. The essence of the NDIS is that participants should have choice and control over what

mix of supports wil best help them achieve their goals, so goal setting is fundamental.

But so too is identifying what therapeutic support wil help in achieving those goals, and

good information about what is likely to be effective is necessary for this purpose.

97. A defining characteristic of a market – where they exist – is that consumers in that

market have enough information to choose among the products on offer. Imbalance in

the knowledge of consumers vis-à-vis providers, is referred to as ‘information asymmetry’

and leads to market failure

.41

98. Information asymmetry is not the only reason for market failure, for example, in parts of

Australia there may not be an adequate supply of professionals and other staff to meet

needs, a situation sometimes described as ‘thin markets’

.42

99. Al this points to the need for active ‘market stewardship’ rather than simple market

regulation

,43 or hoping that markets wil work their magic without any superintendence.

There is thus an important role of ‘market stewards’

,44 such as the NDIA and the NDIS

Commission, including in ensuring there is adequate information to participants to make

informed choices

.45

100. There is known to be a long gap – measured in years but estimates and methods for

estimating the length of the gap vary – between new knowledge about treatments in

41 Giza, Wojciech (2024), 'Asymmetric information as a market failure in retrospect

The Elgar Companion to Information Economics', in Daphne R. Włodarczy Raban, Julia (ed.),

The Elgar

Companion to Information Economics (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing), 106-17.

42 Reeders, Daniel, et al. (2019), 'Market Capacity Framework: An approach for identifying thin markets in

the NDIS', (Sydney: Centre for Social Impact:).

43 Carey, Gemma, et al. (2018), 'The Vexed Question of Market Stewardship in the Public Sector:

Examining Equity and the Social Contract through the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme',

Social Policy & Administration, 52 (1), 387-407.

44 Independent Review into the National Disability Insurance Scheme (2023), 'Final Report: Working

together to deliver the NDIS', (Canberra: The Review).

45 In the longer term, market regulation in the NDIS needs to reconcile the individualistic/personalism

view of participants in a market and the contemporary public policy concept of co-design and co-

creation, see, for example, Ongaro, Edoardo, Rubalcaba, Luis, and Solano, Ernesto (2025 (in press)), 'The

ideational bases of public value co-creation and the philosophy of personalism: Why a relational

conception of person matters for solving public problems',

Public Policy and Administration, 0 (0),

09520767251318127.

19

link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25

health care and implementation in practi

ce.46 Inclusion of research syntheses in

published guidelines helps but is not a panacea

.47

101. There also appears to be a research-practice gap in disability

.48 An essential step in

addressing the gap is that the new Evidence Advisory Committee, as part of its

determination of the evidence and formulating its recommendations, develop a ‘plain

language’ synthesis/summary of its conclusion

s.49

102. However, mere publication of the evidence of what works, even in a plain language

version, wil not be enough to ensure that participants know when to include art or music

therapy in their plans, and art or music therapists know what the latest available

evidence-based interventions are.

103. Again, it is in the best interests of participants and the sustainability of the NDIS, to

ensure good advice is available to help participants, their carers, and their advocates

make informed decisions about what is likely to make a difference. Evidence updates

might also be provided to therapists.

104.

I recommend that the NDIA consider ways in which better information can be

provided to participants to assist them make informed choices about whether

particular therapeutic supports could be a useful, evidence-based addition to their

plans.

105. Ideally, information would be made available in a tailored way, specifying in plain

language that for this type of domain and for a person with this condition, whether there

is evidence that art or music therapy can help achieve their goals

.50

106. In a quite different context

,51 the University of York has a good website which

provides information about potential outcomes of some types of surgery, taking into

46 Evensen, Ann E., et al. (2010), 'Trends in publications regarding evidence-practice gaps: A literature

review',

Implementation Science, 5 (11), 1-5.; Hanney, Stephen R., et al. (2015), 'How long does

biomedical research take? Studying the time taken between biomedical and health research and its

translation into products, policy, and practice',

Health Research Policy and Systems, 13 (1), 1-18.

47 Freitas de Mel o, Nicole, et al. (2024), 'Models and frameworks for assessing the implementation of

clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review',

Implementation Science, 19 (59), 1-15.

48 Dew, Angela and Boydell, Katherine M. (2017), 'Knowledge translation: bridging the disability research-

to-practice gap',

Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 4 (2), 142-57.

49 I use ‘plain language’ throughout this Report rather than ‘plain English’ to recognise the need for

materials in languages other than English.

50 Perhaps a matrix format could be used, but this might be challenging to develop in a plain language

format.

51 The point of this paragraph is to draw attention to a user-friendly way of presenting data to facilitate an

informed choice. Unlike the example used, which is about acute care, participants in the disability stream

have permanent disabilities. That is not to say, of course, that outcome measures are not relevant.

20

link to page 26 link to page 26

account the characteristics of the individual

.52 The data behind the pictorial display used

is drawn from before and after Patient Reported Outcome Measures completed by

patients who have had that type of surgery. I am not aware of anything similar to this to

help people develop their plans under the NDIS. If it were, participants could have advice

specific to their situation to answer the critical question: If art or music therapy (or any

other therapy for that matter) were added to my plan, what might I expect? This type of

analysis could also be developed using data both from the literature and analysis of

individual participant reports submitted to the NDIA, potential y following revision to

standard templates for therapists’ reports on participant progress

.53

107. The second problematic element of the phrasing of ‘evidence based’ is that one

might infer that art or music therapy is provided out of an overall therapeutic context of

the participant.

108. The point of art and music therapy is to contribute to achieving the functional

outcomes and goals established by and for the individual receiving those services. They

should not be conceived of as part of a smorgasbord approach to achieving goals (one

of those, and one of those), but rather as an integrated, holistic approach.

109. The emphasis of the NDIS is, and should be, that supports in combination are to

achieve the individual’s goals. Art or music therapy may, subject to the evidence, be

appropriate contributions linked logically, and in an evidence-based way, to a particular

goal or goals for an individual. The emphasis of the NDIS is appropriately on the holistic

combination of supports that together provide support to meet the individual’s goals. So,

it is the cluster of supports which leads to achievement of a cluster of goals. Evaluating

the contribution of any one intervention is often difficult to disentangle.

110. I have raised the issue of holistic provision above, in the context of early intervention,

but the same issues apply to all aspects of the NDIS to a greater or lesser degree.

Unfortunately, the literature mostly only focuses on evaluating each therapeutic support

in isolation.

111. The third problematic element in the literature base is that the research evidence in

any field rarely says something is always beneficial or always not, rather, the critical

question is almost always how much and in what circumstances.

52 https://www.york.ac.uk/che/patient-outcome-tool/

53 Wallace, Jacqueline (2022), 'An Arts Therapists Guide to NDIS Therapy Report Writing', (North Brighton:

ANZACATA). The NDIA also provides guidance on reporting.

21

link to page 27 link to page 27

112. Phrased more formally, the key policy question is

in prospect, in what cases is art or

music therapy a reasonable and necessary therapeutic support as an alternative to art or

music activities. Possible factors may include, among others:

• Diagnoses and complexity (e.g., level of verbal communication)

• Treatment goals and outcomes (e.g., music activities are not a reasonable

alternative to some forms of therapy such as neurological music therapy)

• How much music therapy is reasonable and necessary in key scenarios.

113. As I have argued above, these factors can be assessed in prospect. For people like

the participant, is there rigorous evidence that art or music therapy might make a

difference in achieving their functional outcomes?

114. If art or music therapy were then added to the participant’s plan, progress might be

measured concurrently (or in retrospect). That is, given the specific circumstances of this

participant, working with this therapist, we see a trajectory of change from before the

support was provided until now, with reports to the NDIA being able to identify any

incremental benefit compared to the cost of the support.

115. Over time, the NDIA could use this data set to supplement the published literature to

identify, standardised for the type of participant, what expected trajectories might be, and

whether specific therapists are associated with better or worse trajectories for the

participant.

116. Public provision of provider- or team-specific information about impa

ct54 would assist

participants to choose amongst providers/teams, consistent with effecting the NDIS goal

about choice and control

.55

117. Returning to the question of ‘what is evidence?’, at minimum ‘evidence’ is about

systematic, controlled studies. By ‘controlled’ here I mean studies that compare the use

of art or music therapy with usual services, or with art or music activities not under the

guidance of an art or music therapist.

54 Information about names, locations and other attributes (e.g., languages spoken) of therapists is readily

available, but no information is provided about therapist quality.

55 The evidence about public provision of comparative quality data in health care is mixed; see Metcalfe,

D., et al. (2018), 'Impact of public release of performance data on the behaviour of healthcare consumers

and providers',

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (9). There may also be perverse effects, as

providers may distort data provision. That said, if choice and control is to be effected, it is important that

participants, carers and advocates are as fully informed as possible when selecting among potential

providers.

22

link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 28

118. Although randomisation of groups to receiving or not receiving these supports or not

is ideal, other methods of control – such as case control studies – may yield comparable

information

.56 The point here is that there needs to be good evidence that the supports

achieve benefits in specific circumstances, in addition to reports of individual stories, for

a support to meet the threshold of ‘evidence based’ contemplated in the NDIS

definition

.57

119. A further weakness of the literature of the effectiveness of art and music therapy is

that the definition of art or music therapy used in the evaluations is often not as clear as

it could be, and so the conclusions from the literature are not always easily able to be

translated into policy. There are exceptions, of course, Hu et al.’s review of art therapy

has a table describing the treatment for each of the key articles reviewed

.58

120. Even when the interventions are well described, they might be quite heterogenous.

One systematic review noted that ‘the nature of music interventions … varied largely

across the studies

.’59

121. The Cochrane Review of music therapy in autism spectrum disorders described the

included studies thus:

The majority of studies included in this review examined music therapy in an

individual (i.e. one-to-one) setting (n = 13). In eight trials, music therapy was

delivered in a group setting. One study reported that music therapy was delivered

either individually or in small groups of up to three people, (another) applied a family-

based setting where parents or other family members were also involved in therapy

sessions. In four studies, it was unclear whether music therapy sessions were

conducted in an individual or group setting. The frequency of music therapy sessions

ranged from daily to weekly. In seven studies music therapy was provided daily, all

with a very short duration of one or two weeks. Of the studies that provided music

therapy over a longer time period, it was provided weekly in nine studies, twice

weekly in six studies, and in the remaining studies three, four, or six times per week.

One study randomised to either one or three session per week. The duration of

sessions ranged from 10 to 60 minutes with a median of 30 minut

es.60

56 Benson, Kjell and Hartz Arthur, J. 'A Comparison of Observational Studies and Randomized, Controlled

Trials',

New England Journal of Medicine, 342 (25), 1878-86.; Concato, John, Shah, Nirav, and Horwitz

Ralph, I. 'Randomized, Controlled Trials, Observational Studies, and the Hierarchy of Research Designs',

New England Journal of Medicine, 342 (25), 1887-92.; Pocock Stuart, J. and Elbourne Diana, R.

'Randomized Trials or Observational Tribulations?',

New England Journal of Medicine, 342 (25), 1907-09.

57 The NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission discusses the concept of an evidence hierarchy in its

Evidence-Informed Practice Guide, see pages 4 +.

58 Hu, Jingxuan, et al. (2021), 'Art Therapy: A Complementary Treatment for Mental Disorders',

Frontiers in

Psychology, 12 (686006), 1-9.

59 Jordan, Catherine, Lawlor, Brian, and Loughrey, David (2022), 'A systematic review of music

interventions for the cognitive and behavioural symptoms of mild cognitive impairment (non-dementia)',

Journal of Psychiatric Research, 151, 382-90.

60 Geretsegger, Monika, et al. (2022), 'Music therapy for autistic people',

Cochrane Database of Systematic

Reviews, (5), CD004381. Page 21

23

link to page 29 link to page 29 link to page 29

122. Other reviews have made similar comments about the heterogeneity of what an art or

music therapy intervention might be. Ideally, as mentioned above, we should be able to

address the

how much question: we should be able to compare the effects of a one-on-

one intervention compared to a group session compared to no art or music therapy.

123. Similarly, it was often not clear what was the marginal benefit of an additional

session: should the therapy intervention be eight sessions with a therapist or ten? How

long should each session be to achieve the benefit?

124. Most importantly, there is also the question of who should provide each service?

125. There is an increasing expectation of health and disability professionals that they

should be able to work to their full scope of practice, using all the skil s and knowledge

they acquired in their professional training

.61 The corollary is that when those skil s are

not needed, the support/activity could be done by someone without those skil s and for a

lesser cost.

126. Specifically, should the role of the professional therapist be to design a program for

the person, with implementation the responsibility of the carer providing the support in an

integrated participant and carer-centred way? For example, the music therapist might

write a song which the parents sing and teach the participant to sing, to help with

undertaking hand washin

g62 or other everyday activities. The therapist might also train a

schoolteacher in appropriate techniques

.63 Or should the therapist delegate some of a

program to an assistant professional? In NDIS parlance, this might mean that the

therapist designs, and the next few sessions are art or music activities rather than art or

music therapy, with the therapist having another session later to monitor progress.

127. The reverse is also true: the art or music therapist might work with other therapists to

design an integrated multi-disciplinary program which the art or music therapist

implements on behalf of the whole team.

128. However, all this presupposes a truly multi-disciplinary way of working, easier in

organisational settings than in the home or a therapist’s rooms is in solo practice. As one

music therapist reflected to this review:

But we have lost the transdisciplinary ways of working that are often a signature of

organisation-based music therapy practice, particularly because music therapists can

61 Scope of Practice Review (Reviewer: Mark Cormack) (2024), 'Unleashing the Potential of our Health

Workforce: Final Report', (Canberra: The Review).

62 This is a real example provided in the submission from AMTA

63 Bentley, Laura A, et al. (2023), 'A translational application of music for preschool cognitive

development: RCT evidence for improved executive function, self‐regulation, and school readiness',

Developmental Science, 26 (5), e13358.

24

link to page 30 link to page 30 link to page 30

create motivating and rewarding conditions for people to rehearse and maintain skills

so we often support goals of our colleagues, as well as focusing on creative,

expressive, psychosocial emotional goals.

129. Final y, to what extent should art or music therapy be seen as time-limited, designed

to build capacity so that participants and their families/carers can use the techniques

they have learned (e.g., calming music) in an ongoing way without the presence of the

therapist?

130. Unfortunately, the published literature does not provide definitive answers to these

questions, pointing to a gap in the literature and a potential research agenda.

The quality of the literature

131. As evidenced in the submissions and from my own analysis, there is a growing

literature about the benefits of art and music thera

py,64 and a number of systematic

reviews. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses look across a number of studies, or

combine a number of studies, to get an overall picture of what is happening in a field and

can more precisely measure effect size. By combining studies one can be more certain

of their generalisability.

132. A systematic review generally assesses the quality of included studi

es.65 For both art

and music therapy, much of the literature is stil weak – poor quality designs, low

numbers – probably a sign that the fields are stil developing. A recent systematic review

of music therapy had this to say about the quality of the literature:

The literature had a number of limitations including small sample sizes, lack of

control group, lack of randomisation and lack of double blinding in (randomised

controlled trial) studies

.66

133. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the overal pattern is that both art and music

therapy can make a meaningful difference in goal achievement for people with some

conditions.

64 Australian Music Therapy Association (2024), 'Music therapy Disability evidence summary 2024:

Person-first language', (Beaumaris, Vic: AMTA).

65 Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group,

(2004), 'Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations',

BMJ, 328 (7454), 1490-94.;

Guyatt, Gordon H., et al. (2008), 'What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians?',

BMJ, 336 (7651), 995-98.

66 Jordan, Catherine, Lawlor, Brian, and Loughrey, David (2022), 'A systematic review of music

interventions for the cognitive and behavioural symptoms of mild cognitive impairment (non-dementia)',

Journal of Psychiatric Research, 151, 382-90.

25

link to page 31 link to page 31 link to page 31 link to page 31 link to page 31

134. It is important to emphasise that not all systematic reviews are themselves of good

quality. Indeed, there are now tools to assess the quality of systematic reviews (e.g. risk

of bias)

.67

135. The literature essentially examines the

clinical benefit of the interventions, with

almost no studies of the

cost-effectiveness of the interventions

,68 whether increased

investment in the therapy would yield additional benefits, or whether reduced investment

could achieve the same benefit.

136. There was only one study of art therapy reported in the Tufts cost effectiveness

registry, and this related to non-psychotic mental health disorders

.69 This systematic

review cautioned about drawing definitive conclusions, given the heterogeneity of the

studies, risk of bias, and generally poor quality.

137. ANZACATA also drew my attention to an economic impact study about art therap

y.70

138. The Tufts cost effectiveness registry included only two studies related to music,

neither directly related to music therapy with people with disabiliti

es.71 Neither study

allows one to make definitive conclusions about the cost effectiveness of music therapy

for people with disabilities generally.

139. This paucity of evidence about cost-effectiveness of both modalities is unfortunate to

the say the least, and the NDIA might consider commissioning research to address this

gap.

67 Shea, Beverley J., et al. (2017), 'AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include

randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both',

BMJ, 358 (j4008), 1-9.

68 The Tufts cost-effectiveness registry is the accepted registry of such studies: Thorat, Teja, Cangelosi,

Michael, and Neumann, Peter J. (2012), 'Skills of the Trade: The Tufts Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Registry',

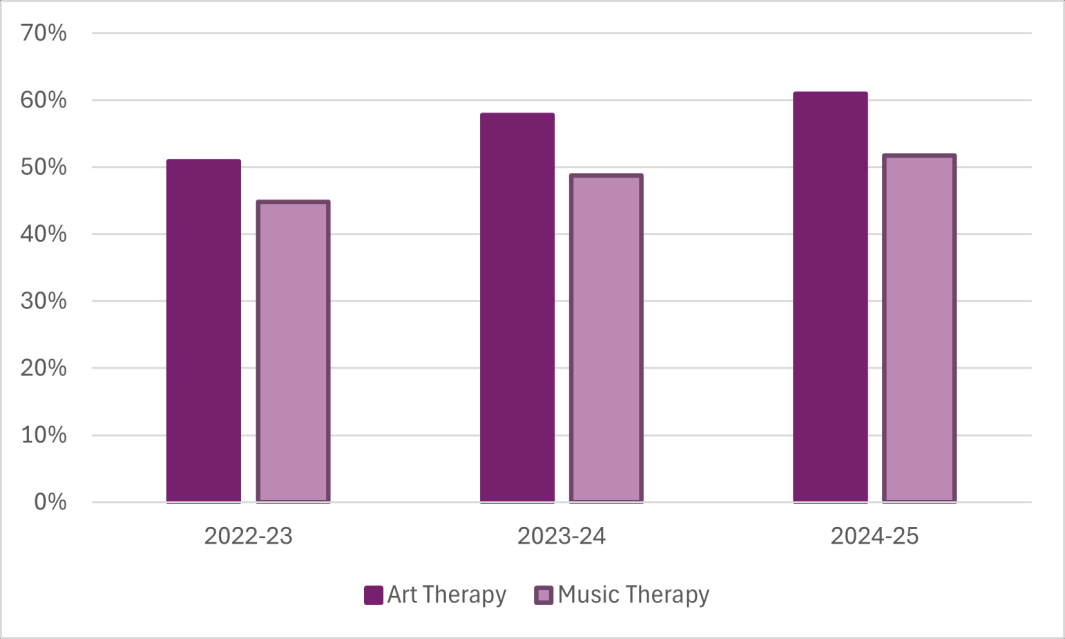

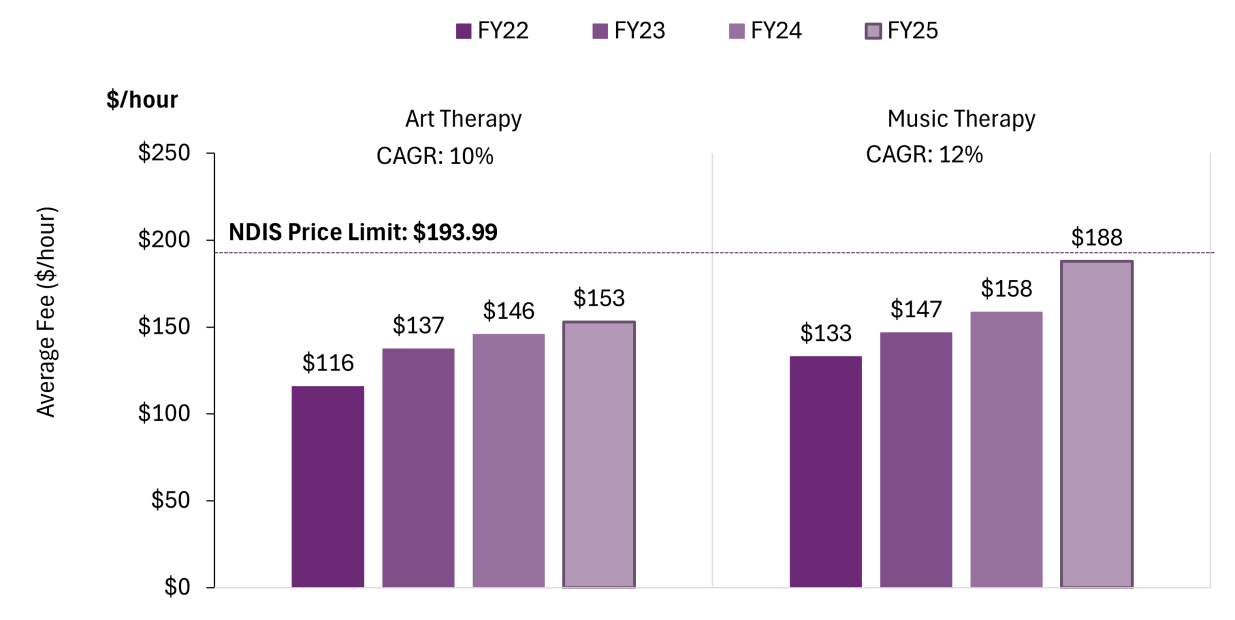

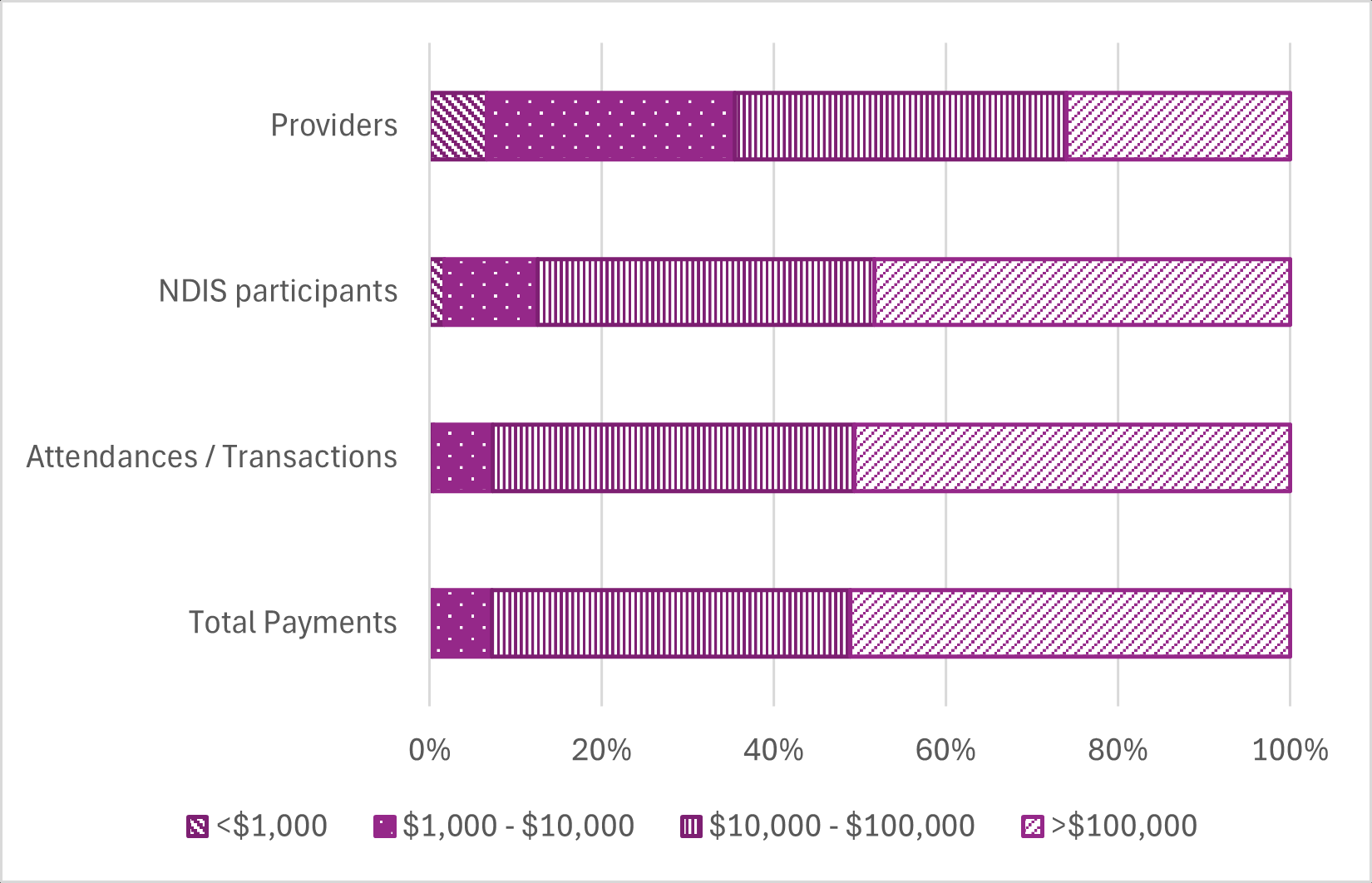

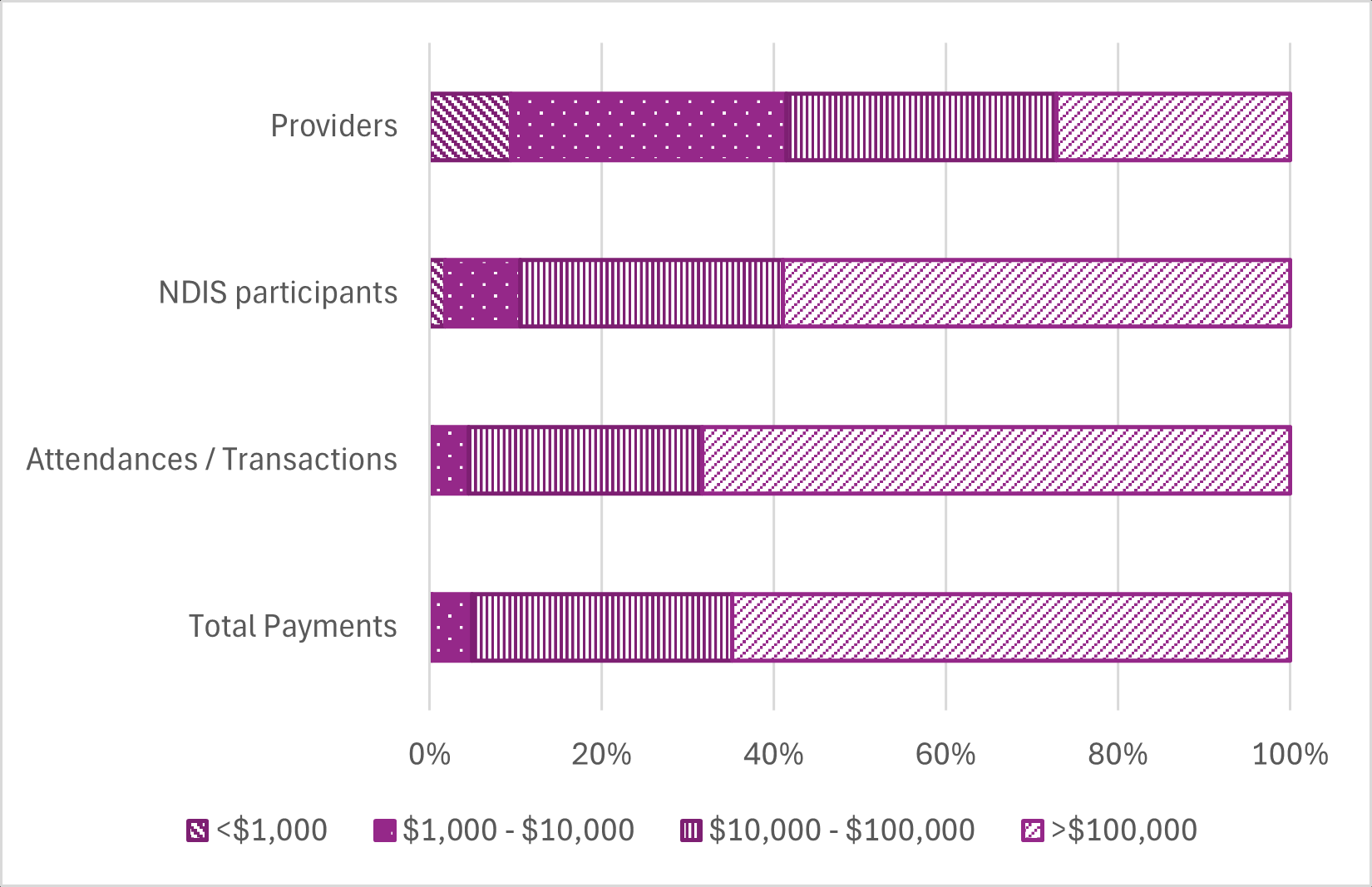

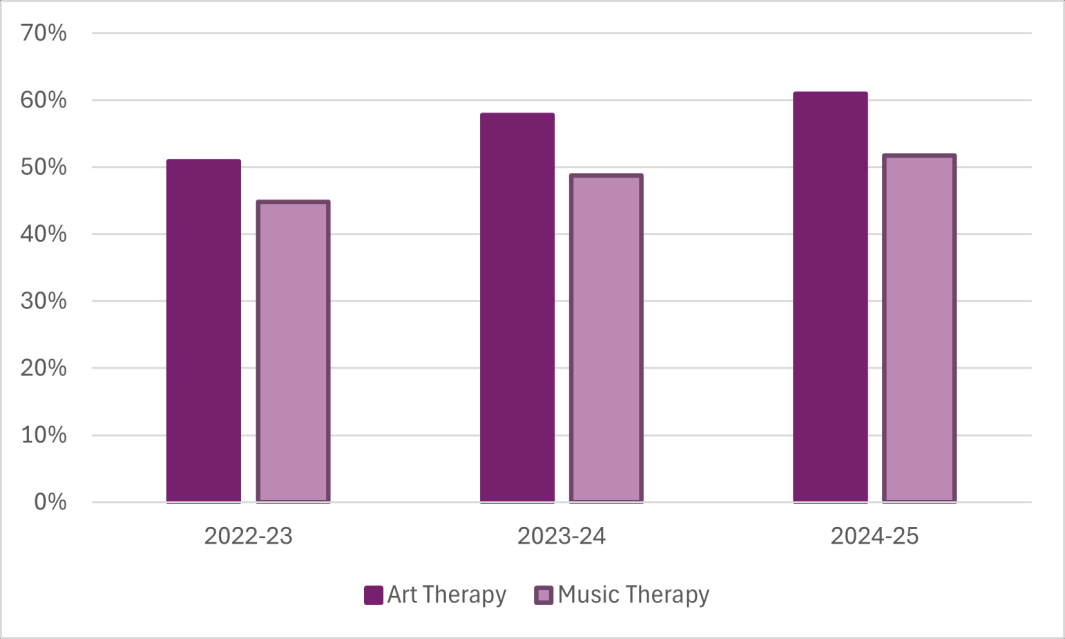

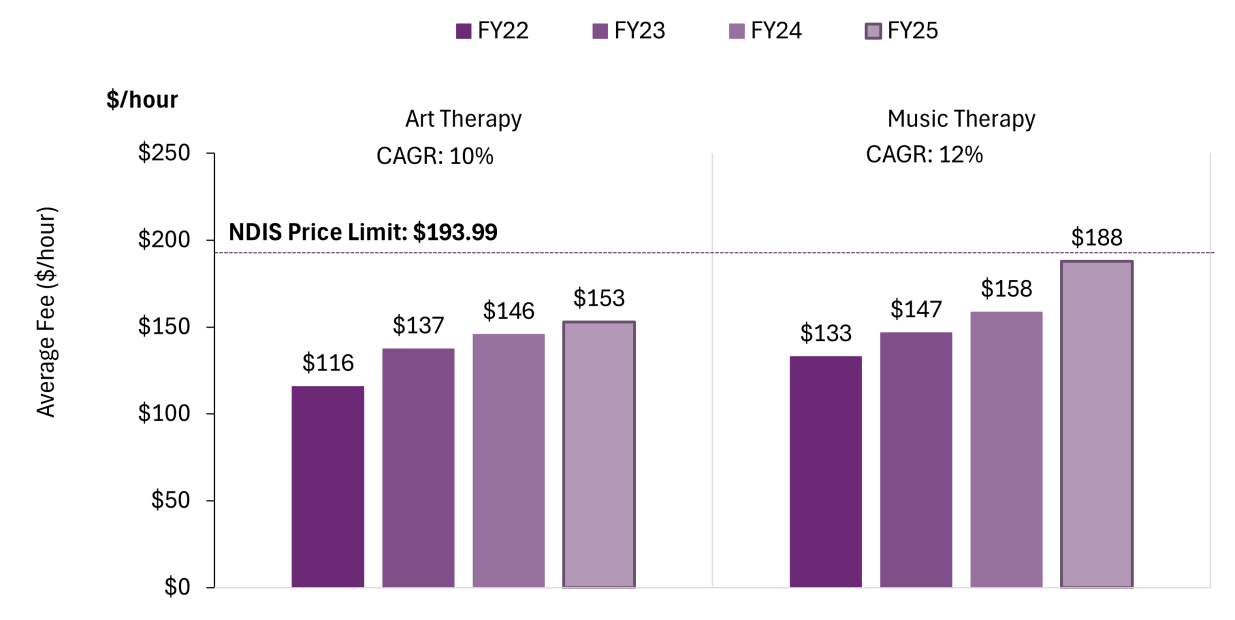

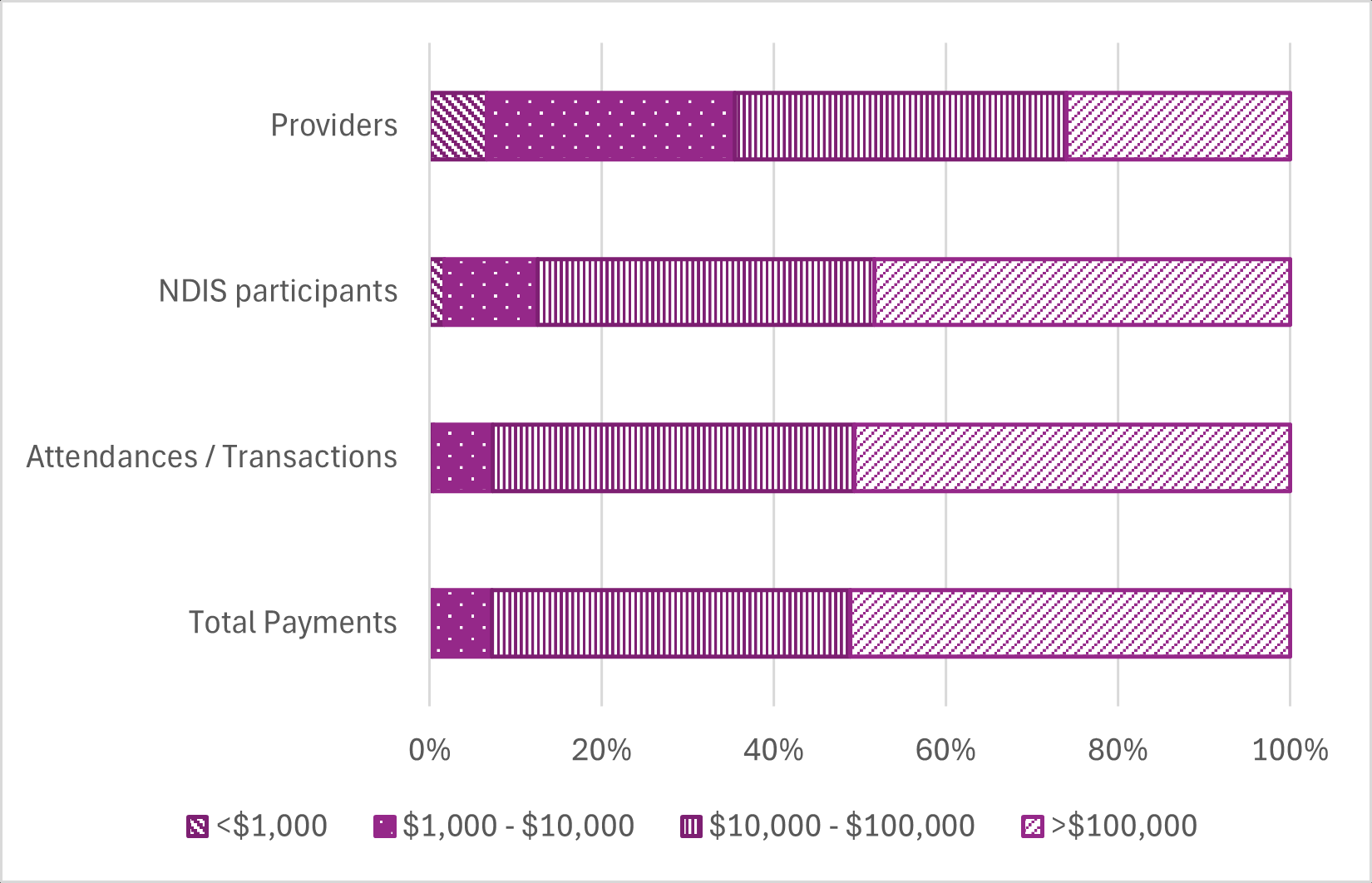

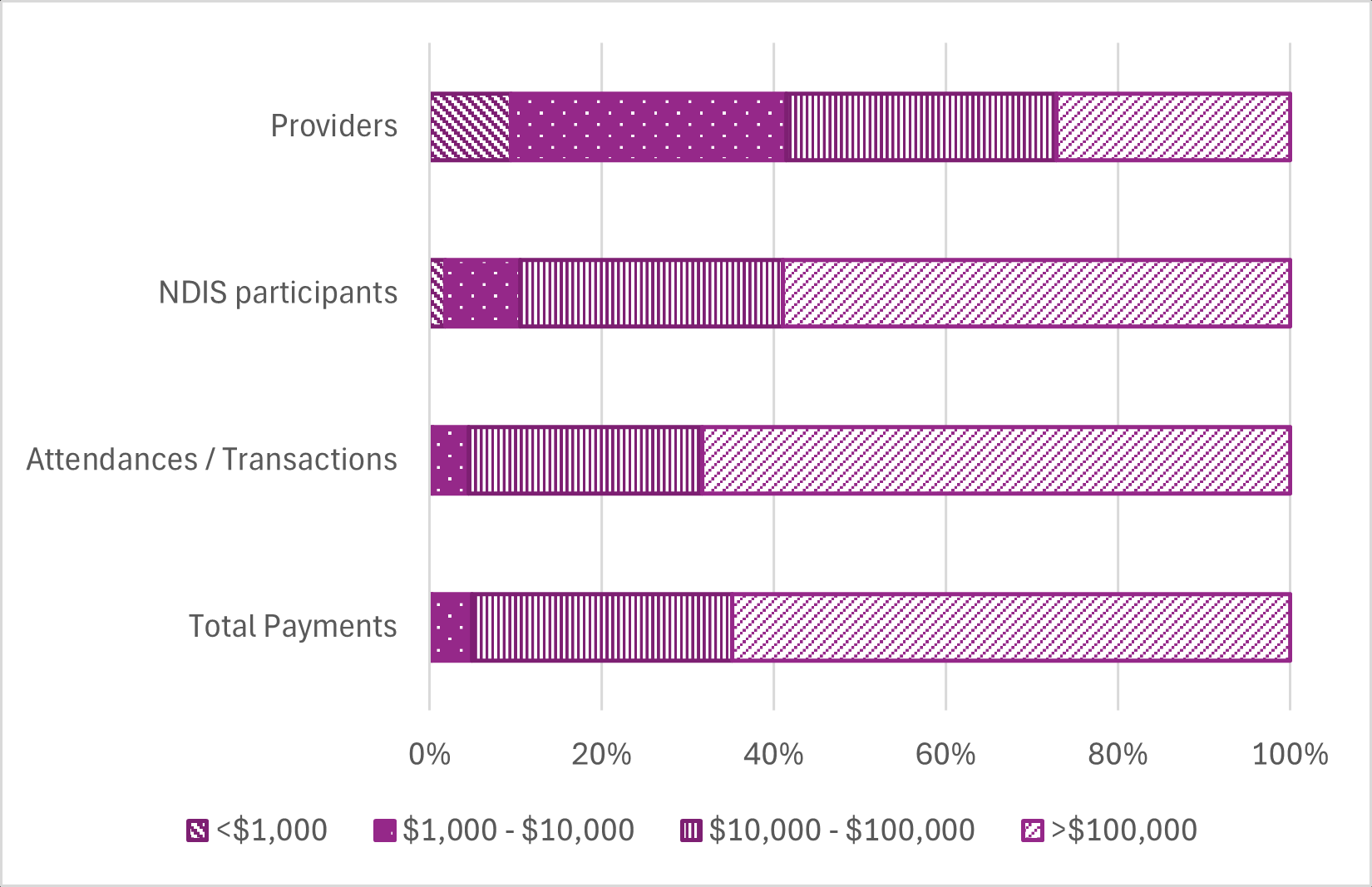

Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis, 3 (1), 1-9.