Research Team

Ciara Smyth, Trish Hill, Andrew Griffiths, Ilan Katz and Aran Mahenthirarajah

For further information:

Dr Ciara Smyth, x.xxxxx@xxxx.xxx.xx, 02 9385 7844

Social Policy Research Centre

UNSW Sydney 2052 Australia

t +61 (2) 9385 7800

f +61 (2) 9385 7838

xxxx@xxxx.xxx.xx

www.sprc.unsw.edu.au

© UNSW Sydney 2017

The Social Policy Research Centre is based in Arts & Social Sciences at UNSW

Sydney. This report is an output of the

Post Implementation Review of No Jab, No

Pay 2015 Budget measure research project, funded by the Australian Government

Department of Social Services.

Suggested citation:

[to follow] Smyth, C., Hill,T, Griffiths, A., Katz, I. and Mahenthiraraja, A. (2017).

Post

Implementation Review of the No Jab, No Pay 2015 Budget Measure (SPRC Report

09/17). Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Sydney.

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

ii

link to page 3 link to page 4 link to page 4 link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 30 link to page 34 link to page 49 link to page 52 link to page 55 link to page 65 link to page 70 link to page 73 link to page 73 link to page 76 link to page 80 link to page 87 link to page 94

Contents

Contents .......................................................................................................... i

Tables ............................................................................................................ ii

Figures ........................................................................................................... ii

Glossary ......................................................................................................... iii

Executive summary ........................................................................................ 4

Policy design ........................................................................................... 5

Issues and risks ...................................................................................... 6

Communications ..................................................................................... 7

Management information ......................................................................... 8

1

Introduction ........................................................................................... 11

2

Literature review .................................................................................... 12

2.1 Immunisation rates .......................................................................... 13

2.2 Factors contributing to incomplete childhood immunisation ............ 14

2.3 Increasing immunisation uptake ...................................................... 15

2.4 The No Jab No Pay budget measure .............................................. 19

3

Methodology .......................................................................................... 20

3.1 Document review ............................................................................ 21

3.2 Data scoping ................................................................................... 21

3.3 Qualitative stakeholder consultation ................................................ 21

3.4 No Jab, No Pay workshop ............................................................... 22

3.5 Analysis and synthesis of findings ................................................... 22

4

Findings ................................................................................................. 23

4.1 Policy Design .................................................................................. 23

4.2 Implementation and Policy Design .................................................. 28

4.3 Dealing with issues and risks .......................................................... 32

4.4 Governance ..................................................................................... 47

4.5 Service delivery ............................................................................... 50

4.6 Communications ............................................................................. 53

4.7 Management information ................................................................. 63

5

Discussion ............................................................................................. 68

6

Impact Evaluation Framework ............................................................... 71

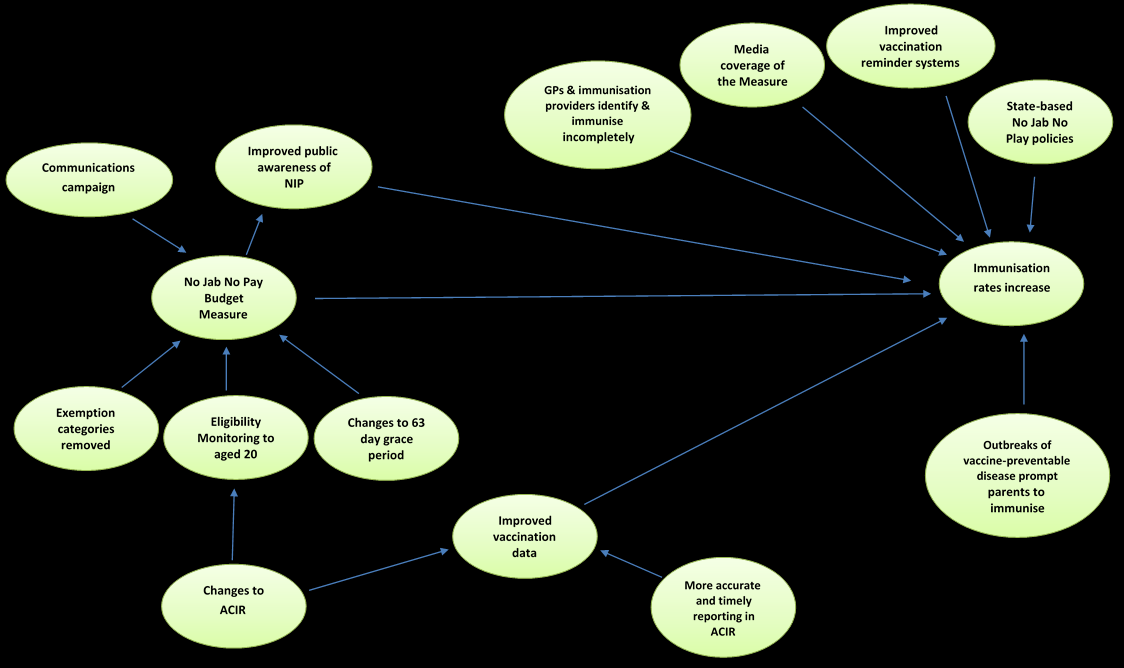

6.1 No Jab, No Pay theory of change ................................................... 71

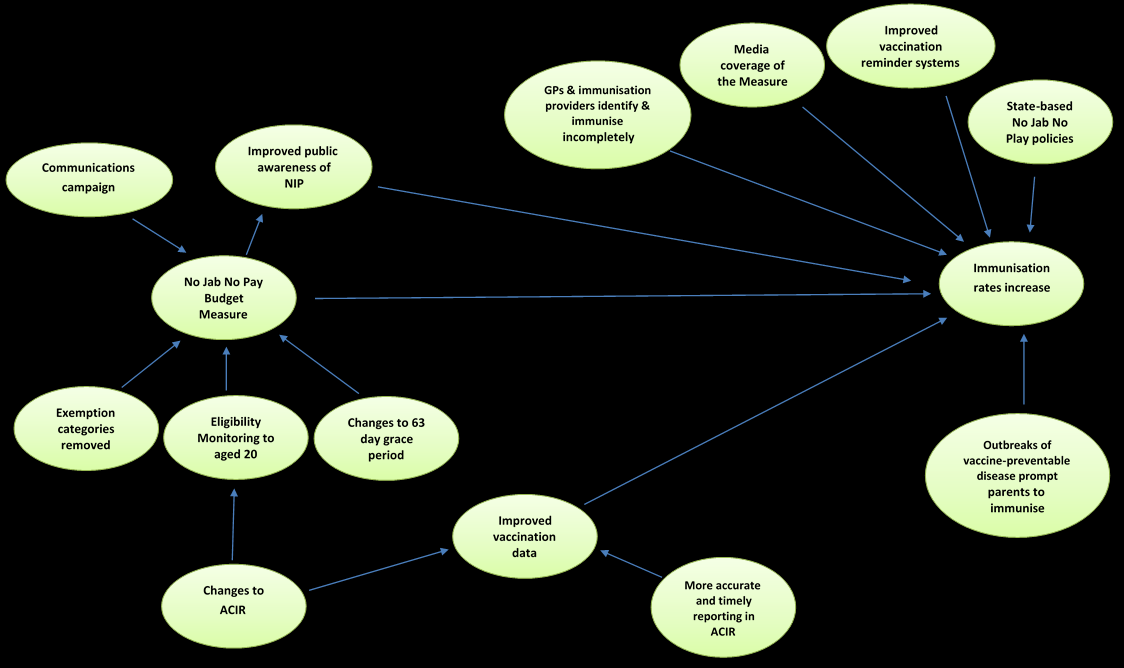

6.2 No Jab No Pay Policy logic ............................................................. 74

6.3 Data Scoping ................................................................................... 78

6.4 No Jab, No Pay Impact Evaluation Framework ............................... 85

7

References ............................................................................................ 92

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

i

link to page 22 link to page 35 link to page 55 link to page 55 link to page 83 link to page 75 link to page 78

Tables

Table 1 Research areas, questions and data sources ................................. 20

Table 2 No Jab No Pay DSS risk log ............................................................ 33

Table 3 NJNP communication objectives, department responsible & target

audience ....................................................................................................... 53

Table 4 Data sources for impact evaluation ................................................. 81

Figures

Figure 1 No Jab No Pay Theory of change .................................................. 73

Figure 2: No Jab, No Pay Policy logic model................................................ 76

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

ii

Glossary

ACIR Australian Childhood Immunisation Register

AIR

Australian Immunisation Register

CCB Child Care Benefit

CCR Child Care Rebate

COs

Conscientious Objectors

DET

Department of Education and Training

DHS Department of Human Services

Health Department of Health

DSS

Department of Social Services

ES

External stakeholders

FTB

Family Tax Benefit

GS

Government stakeholders

NJNP No Jab, No Pay

VOs

Vaccination Objectors

MIA

Maternity Immunisation Allowance

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

iii

Executive summary

The Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) commissioned the

Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC) at UNSW Sydney to undertake a Post

Implementation Review (PIR) of the

No Jab, No Pay 2015 Budget measure (the Measure).

The intended outcomes of this review were:

•

to determine whether the Measure was implemented effectively by measuring

successes and challenges that have been encountered in the first 6–12 months of

the Measure's implementation

•

to provide a framework for the subsequent impact evaluation.

The PIR was undertaken to assess implementation successes and challenges and also to

inform the development of the impact evaluation framework. The PIR was guided by

several key questions:

Policy design

Has implementation been consistent with the Measure's policy design?

If there have been any deviations from the original design, have these been

positive or negative in nature?

Issues and risks

What successes and challenges (including design, system, data, communications,

and uptake of immunisation by the target populations) were encountered in

implementing the Measure?

Governance

Did governance and decision-making mechanisms help or hinder the successful

implementation of the Measure?

Service delivery

Has the service delivery model resulted in impacted recipients having positive or

negative encounters?

Communications Did the communication strategy and Departmental communication plans

successfully support the implementation of the Measure?

Did the Communication Working Group effectively manage communication issues

as they arose?

Management

How has the policy and system design impacted upon the data available to date

information

regarding rates of immunisation and eligibility for both family assistance (Family

Tax Benefit Part A supplement) and child care payments?

The methodology for the PIR included:

• a document review of publicly available and internal documents from the four

departments involved in implementing the Measure: DSS, Department of Human

Services (DHS), Department of Health (Health) and Department of Education and

Training (DET)

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

4

• a data scoping exercise

• qualitative stakeholder consultation with 17 government and external stakeholders

• a workshop with departmental staff involved in implementing the Measure.

The data gathered through these sources were analysed and synthesised in order to

answer the research questions guiding the PIR.

Policy design

The rationale of successive governments in placing mutual obligations on recipients of

social security and family assistance payments is based on the concept of encouraging

behaviours beneficial to individuals and the broader community. Conditionality is a key

priority of the government, and this was reflected in the design of the No Jab, No Pay

policy in setting out specific immunisation requirements that a child must meet to be

eligible to receive a benefit or payment. The policy’s intent sought to reinforce the

importance of immunisation as a measure to ‘protect public health’ and highlight that the

choice made by families to not immunise children should not be supported by taxpayers in

the form of government benefits.

The policy was designed to extend existing immunisation eligibility requirements for child

care and family payments through three key mechanisms:

• removal of vaccination objection as a valid exemption category

• requirement for individuals up to 20 years of age to be fully vaccinated to receive

family payments

• removal of the 63-day initial grace period for new child care claimants to either get

up to date with immunisations or commence a catch-up schedule.

The review found that implementation was consistent with the Measure's policy design.

Activation of the three mechanisms was supported by the detailed implementation plans

from DSS and DHS, with the latter outlining the expansion of the Australian Childhood

Immunisation Register (ACIR) to the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR).

Implementation was also supported by the complementary measures introduced by

Health.

Most stakeholders felt that the implementation of the Measure had been consistent with

the policy’s design. While the policy had undergone some minor changes since it was

originally announced, these were generally carried out well before the Measure was

launched and did not constitute significant deviations from the policy design.

Two key implementation challenges concerned the need to:

• extend the payments beyond the initial grace period for existing recipients to

prevent parents from losing access to child care payments when their child’s

immunisations were up to date but the ACIR records did not reflect this (due to

delays in states/territories updating the ACIR)

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

5

• amend the continuous/rolling catch-up anomaly which could have enabled parents

to delay vaccination indefinitely and continue to receive family payments.

Both of these were addressed promptly and appear to have prevented any negative

impacts for recipients, and supported the policy’s initial design.

A further challenge identified by stakeholders concerned the eight-month timeframe

between the policy announcement and its implementation. Key implementation challenges

included the changes to the ACIR, the uncertainty around when the legislation would pass

and limited timeframes for engaging and communicating with stakeholders. The tight

timeframe appears to have presented difficulties for health service providers at state and

territory level who were responsible for immunising children.

Issues and risks

A number of procedures were put in place to identify issues and risks that could negatively

affect implementation of the Measure. These included:

•

an issues register and risk log maintained by DSS

•

an issues register maintained by DHS

•

the establishment of an Interdepartmental Committee (IDC) with Senior Executive

staff and an Executive Level working group were also key to identifying, discussing

and strategising to mitigate issues and risks.

Identified challenges with respect to policy design included: calls in social media for a High

Court challenge to the legality of the Measure; feasibility of using the Secretary’s

Exemption to address challenging clinical circumstances; fraudulent medical exemption

forms; and eligibility monitoring. Identified system challenges included:

• Australian Government and state/territory interactions in the case of delays in

states/territories uploading immunisation data to the ACIR

• vaccine availability.

Identified data challenges included concerns about the quality of the data in the ACIR,

delays in uploading data, and the ability to monitor vaccination objection. An additional

system challenge was the increased workload for state/territory services, including local

councils, public health units and vaccination providers, who reported that they were

overwhelmed by the increased workload associated with the commencement of the

Measure.

s47E(d)

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

6

Governance

The governance structure established for the Measure included a high level (Senior

Executive) Interdepartmental Committee (IDC) and an Executive Level Working Group that

both met regularly to handle practical implementation issues. These were in addition to the

‘business as usual’ governance arrangements in each agency. There was also a separate

Communications sub-committee, as well as some department-specific steering

committees. These governance structures were effective in identifying, and strategising to

mitigate issues and risks.

Service delivery

The stakeholder consultation provided some insight into whether recipients had positive or

negative encounters with service provision. Australian Government and external

stakeholders held divergent views about this. Most government stakeholders felt that

recipients had a positive experience with the new requirements, which they attributed to

the public’s acceptance of the overall aims of the Measure. Government stakeholders

nominated two areas in which recipients’ experiences were negative. These centred on

confusion for recipients around the process of updating their children’s vaccination details

(and delays in having ACIR records updated), and vaccination objectors’ opposition to the

Measure. The external stakeholders characterised recipients’ experiences with

implementation of the Measure more negatively. They felt that recipients’ experiences

were dependent on their child’s vaccination status, highlighting the difficulties faced by

many parents whose children were immunised overseas in fulfilling their obligations, as

well as the perceived inadequate communication around the Measure from government.

External stakeholders felt that a lack of knowledge and confusion around the impact of the

Measure caused anxiety for many parents.

Communications

The Measure’s communication activities were the joint responsibility of DSS, Health, DHS,

and DET, with the DSS’ strategy outlining the agreed overarching communication

approach. Complementary communication strategies were developed by DHS and Health.

Communication activities were undertaken by DSS to inform parents, service providers

and other stakeholders of the changes. Health developed a communication plan for

vaccination providers, including general practitioners. DHS also developed a

communication implementation plan and undertook a range of communication activities

including: general information letters for recipients, letters for CCB recipients, letters for

FTB recipients, and additional letters for parents whose child/ren’s immunisation status

was either not up to date, unknown (because child was not linked) or was mismatched with

information on file. DET was responsible for communicating with child care services via the

Child Care Management System (CCMS) Helpdesk.

Most government stakeholders agreed that the Measure’s communications strategy,

including letters to recipients and health providers, as well as general media, was effective

in supporting implementation. Nevertheless, many were aware of issues that hampered

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

7

communications, including: the tight timeframe for implementation resulting in delays in

getting information to recipients and health professionals, the complexity of the message

and confusion due to different requirements for different payments. Positive outcomes of

the communications strategy included consistency in delivering the same message across

departments and utilising as many channels as possible to communicate the changes

resulting in high levels of awareness. External stakeholders were generally less positive

about communications surrounding the Measure. Most reported that they had not received

adequate information about the Measure, or that there were gaps in the information

provided which hindered their ability to explain the changes to recipients.

Management information

The document review highlighted concerns about the completeness of the data in the

ACIR, the capacity to monitor vaccination objectors in the future, concerns about data

linkages and the management information that was produced to monitor implementation

and impact.

Stakeholders noted that implementing the Measure necessitated a significant amount of

additional information being entered into the ACIR, as children aged 10 up to 20 years now

needed full vaccination histories recorded. Linkages between the Centrelink payment

database and the ACIR also needed to be updated. Several government and external

stakeholders commented that the ACIR had improved, but that some short-term issues

were experienced, including delays uploading data, data cleansing and parental angst.

Other government stakeholders referred to the additional work to establish linkages

between DHS and the ACIR. It was acknowledged that the process was not without its

challenges but that linkages were ultimately successfully established.

Regular reports from Centrelink (DHS) data were provided to DSS, DET and Health to

determine whether the Measure had resulted in any changes to the number of families

receiving payments. Minutes from meetings of the IDC and the Working Group provide

some information about the impact of the Measure on child care payments and on FTB

Part A supplement payments.

The impact evaluation should examine the quality of the data on immunisation rates in the

ACIR. While the ACIR contains historical information on registered vaccine objections, the

capacity to monitor ongoing levels of vaccine objection in the community has reduced.

Options to continue to monitor vaccination objection, as part of a broader inquiry into

community understanding and confidence in vaccines, should be examined as suggested

by submissions to the Senate Inquiry.

PIR summary conclusions

Overall, the implementation of the Measure went relatively smoothly from a policy

perspective. Governance arrangements, risk mitigation strategies and communication

strategies were put into place, and the Measure was implemented in a flexible manner that

allowed for challenges to be addressed as they arose. Government departments worked

well together and the communication between departments was effective in addressing

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

8

overlaps and gaps. There were additional benefits to the implementation of the Measure,

in particular improvements in the completeness of data in the ACIR.

Despite the effective implementation by the Australian Government there were

considerable difficulties for state and territory officials as well as vaccination providers.

Some of these difficulties resulted from the parameters of the Measure itself. These

included:

• the short timeframes for implementation

• the perceived lack of additional resources provided for states and vaccine

providers, other than the $6 incentive for catching-up overdue children

• the incompleteness of the AIR and backlogs in getting data uploaded onto the

register.

Other challenges may have been better addressed in the implementation, in particular, that

only three states sought additional support for implementing the Measure via primary

health networks, and the perceived inadequacies in support available for state and territory

vaccine providers, despite regular meetings with the Australian Government departments

during implementation.

Overall, the majority of the challenges can be accounted for as ‘teething problems’, which

are to some extent inevitable in the implementation of any complex measure, particularly

when it is required in a short time frame. It is anticipated that most of these challenges will

be resolved and will not affect implementation in the long-term. Perhaps the only long-term

unintended consequence of the Measure has been the loss of ability to track vaccine

objectors and henceforth the Government will need to rely on proxy measures to assess

the extent of vaccination objection in the community.

Although the early implementation has been mostly successfully accomplished, it is not yet

possible to assess whether the Measure itself has been successful. There are early

indications that vaccination rates have improved, but it is not possible at this stage to

attribute changes to the Measure or any particular component of it. An impact evaluation

would need to be undertaken to assess the degree to which the Measure has not only

improved administrative processes, but has led to actual changes in population behaviour,

and whether these have been sustained over time.

The most contentious aspect of the Measure concerns the underlying theory of change,

the long-term effectiveness of a sanctions-based approach as opposed to an incentive-

based approach to public health, and the unintended consequences for children who are

not up to date with vaccinations because of issues other than vaccination objection. These

questions will be tested in any impact evaluation.

Impact Evaluation

Drawing on insights gained through the PIR, options and strategies for conducting the

impact evaluation of the Measure were also developed.

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

9

Two key challenges for any impact evaluation relate to isolating the impact of the Measure

on immunisation rates and trying to establish a baseline measure for determining impact.

As noted in the theory of change model, a range of additional contextual factors may have

had an impact on the immunisation rates. These include state-based policies,

complementary measures introduced by Health and media coverage of vaccination. As

such, isolating the impact of the Measure on immunisation rates will be a challenge. It may

be possible to examine the impact of outside factors through qualitative research, which

should complement the administrative data analysis.

The key questions to be addressed in any impact evaluation would be:

• Did the Measure achieve its intended goal of increasing immunisation rates and

achieving herd immunity in the Australian population?

• To what extent can changes in immunisation rates be attributed to the Measure?

• Were there any unintended impacts (positive or negative) of the Measure?

• Is the Measure cost-effective? (cost benefit analysis)

• Have there been any ongoing implementation challenges following the post-

implementation phase?

We recommend that any impact evaluation adopt a ‘before and after’ mixed method

design, as it will not be possible to utilise a counterfactual or comparison group to assess

impact.

The economic evaluation could draw upon the findings of any impact evaluation and will

model the economic costs and benefits of vaccinating additional children after the onset of

the Measure. Where possible, this analysis will include a geographical breakdown, as the

benefits of vaccinating a child living in an area with low vaccination rates will be greater

than a child living in an area with already high rates of vaccination. Similarly, if possible,

the modelling will include vulnerable groups such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

and CALD children who are at higher risk of vaccine-preventable disease. A broad

estimate of the costs of the evaluation would be around $400,000.

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

10

1 Introduction

The Australian Government Department of Social Services commissioned the Social

Policy Research Centre (SPRC) at UNSW Sydney to undertake a Post Implementation

Review (PIR) of the No Jab, No Pay

2015 Budget measure. The intended outcomes of this

review were:

• to determine whether the Measure was implemented effectively by measuring

successes and challenges that have been encountered in the first 6–12 months of

the Measure's implementation

• to provide a framework for the subsequent impact evaluation.

The report is divided into two main parts: the first presents the findings of the PIR, and the

second outlines a framework for an impact evaluation of the No Jab, No Pay

2015 Budget

measure.

The findings of the PIR are further subdivided. We begin by presenting a select review of

the literature on the impact of similar measures. In the following section, we present the

methodology for the PIR, the research questions guiding the PIR and present the findings

from the document review, the stakeholder consultation and data scoping exercise.

In part two, we present an impact evaluation framework.

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

11

link to page 94 link to page 96 link to page 94 link to page 94 link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 95 link to page 96 link to page 96

2 Literature review

This section presents a select review of the literature with a view to providing some

background to immunisation rates in Australia, interventions designed to increase

immunisation rates and the introduction of the Measure. The review is by no means

exhaustive; rather it aims to provide some context for the PIR.

Immunisation is considered to be a highly effective and cost-effective health intervention

and increasing immunisation rates is a key public health goal at both the national and

global level

(Australian Government, 2014; World Health Organization, 2013). Routine

immunisations for infants began in Australia in the 1950s when immunisation was the

responsibility of individual states and territories. Over time, however, disparities in

immunisation rates between states and territories became evident, with differences

attributed to differential funding of, and access to, vaccines. A national survey in the 1980s

indicated that only 53 per cent of children were adequately immunised. Concern about low

rates of immunisation led to the development of the first National Immunisation Strategy in

1993 and the establishment of the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register

(ACIR) in

1996

(Australian Government, 2014).

In 1997, the

Immunise Australia: Seven Point Plan was launched to increase childhood

immunisation rates. The aim of this program was to increase vaccination rates among the

general population. Strategies to increase immunisation rates introduced under the

Seven

Point Plan included financial incentives for parents and general practitioners, improved

methods for monitoring vaccination coverage, education, research and school entry

requirements

(Australian Government, 2014; Pearce, Marshall, Bedford, & Lynch, 2015;

Ward, Hull, & Leask, 2013).

Under the

Immunise Australia: Seven Point Plan, immunisation status was linked to the

Maternity Immunisation Allowance (MIA) and child care payments (‘Child Care Assistance

Rebate and/or the Child Care Cash Rebate’). Depending on factors such as income, size

of family and type of child care, rebates ranged from $20–$122 for every child per week.

The MIA was a one off payment of $200 for every child that was fully immunised at 19

months of age

(Ward et al., 2013). In order to remain eligible for these payments, parents

were required to provide evidence that their child was fully immunised according to the

immunisation schedule included in the National Immunisation Program (NIP). Parents who

disagreed with vaccination or had philosophical reasons for not having their children

vaccinated could register as ‘conscientious objectors’ in order to continue receiving these

payments

(Lawrence, MacIntyre, Hull, & McIntyre 2004).

The MIA was modified in 2009 and ceased in 2012, and immunisation status was linked to

the existing means-tested Family Tax Benefit (FTB) Part A supplement at ages 1, 2 and 5

years. Parents were exempt from the immunisation requirements if they registered their

‘conscientious objection’1 with DHS

(Ward et al., 2013). Ward, Chow, King, and Leask

1 Based on the data available on the ACIR website, it appears that the recording of conscientious objection

data commenced in 1999.

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

12

link to page 96 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 96 link to page 94 link to page 94 link to page 96 link to page 94

(2012) argue that ‘[l]egislated parental incentives for childhood immunisation have been

broadly accepted among Australian parents and have had a positive impact on uptake and

timeliness’.

Data on children’s immunisation status was held in the Australian Childhood Immunisation

Register (ACIR) (now the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR)). The ACIR was

established in 1996 and included the immunisation data for children registered with

Medicare—roughly 99 per cent of children in Australia

(Hull et al., 2013, p. 149). The

register relied on general practitioners and other vaccination providers reporting

vaccination information to the ACIR after administering vaccines. Children vaccinated

overseas were required to provide proof of vaccinations to Australian vaccination

providers, who entered the information in the ACIR. Proof of vaccination was required for

data to be submitted to ACIR

(Gibbs, Hoskins, & Effler, 2015).

Under the

Seven Point Plan, a General Practice Immunisation Incentive scheme (GPII)

was introduced. The aim of the scheme was to encourage general practitioners to notify

the ACIR of changes of immunisation status of children under 7 who came to their

practice. Under the scheme, general practitioners received a $6 payment for each

notification that a child has been fully immunised according to the schedule

(Ward et al.,

2013). GPII also paid performance funding to general practitioners able to demonstrate

immunisation coverage above 90 per cent for their practice. With respect to child care

attendance, children for whom conscientious objection to vaccination had been registered

could still attend, but could be temporarily excluded in the case of an outbreak of a

vaccine-preventable disease

(Salmon et al., 2006).

The implementation of the

Seven Point Plan led to dramatic increases in vaccination rates

among children. Between 1996 and 2000, vaccination coverage among children aged 12

months increased rapidly to over 90 per cent of infants aged 12–15 months. However,

uptake has since remained relatively stable at around 91 to 92 per cent

(Hull et al., 2013,

p. 164), which is below the OECD average and falls below the levels required for herd

immunity for some diseases

(Harvey, Reissland, & Mason, 2015; Pearce et al., 2015). The

Australian Government Chief Medical Officer and the state Chief Health Officer agreed to

an aspirational target of 95 per cent immunisation coverage rates, consistent with the

World Health Organization’s Western Pacific Region target. This is the level required to

achieve ‘herd immunity’

(Department of Health, 2016). Herd immunity refers to the

required percentage of the population that needs to be vaccinated to prevent the outbreak

of vaccine-preventable diseases

(Danchin & Nolan, 2014). Although the proportion differs

for different diseases, the WHO Western Pacific Region’s standard, based on measles, is

95 per cent of the population

(Wigham et al., 2014, p. 1118). The figure is a whole of

population target, but ideally 95 per cent of the population should be immunised in every

geographic community.

2.1 Immunisation rates

The National Immunisation Program Schedule provides a list of vaccinations that all

Australian children are expected to receive and the age at which they are expected to be

administered

(Australian Government, 2016c). It also identifies the vaccinations to be

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

13

link to page 94 link to page 94 link to page 94 link to page 94 link to page 94 link to page 95 link to page 96 link to page 95 link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 94

provided through school vaccination programs, additional vaccinations that Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander children should receive and additional vaccinations for other ‘at-risk’

groups.

Coverage data for children aged 24 months in 2014 from the ACIR indicate that 91.23 per

cent were up to date with their immunisations. Of the remaining children, 7 per cent were

not up to date with their immunisations and did not have a recorded conscientious

objection, and just 1.77 per cent had a recorded conscientious objection

(Australian

Government, 2016a). These figures suggest that most children’s incomplete vaccination

status are likely to be attributable to causes other than vaccine refusal

(Beard, Hull, Leask,

Dey, & McIntyre, 2016). The picture is complicated by a number of factors, including that

some parents who registered as conscientious objectors nevertheless went on to

vaccinate their children, and also that some children were not registered on the ACIR at

all. Thus the exact proportion of conscientious objectors is difficult to determine.

Nevertheless, it is a very small proportion of the total population.

2.2 Factors contributing to incomplete childhood immunisation

With immunisation rates below the national aspirational immunisation coverage target,

researchers have sought to explore the characteristics of partially and non-immunised

children. The literature identifies two key groups of parents whose children are not

immunised at all or are incompletely immunised. The first group consists of parents who

face barriers to accessing immunisations ‘which may relate to social disadvantage and

logistical barriers’

(Beard et al., 2016; Leask et al., 2012; Pearce et al., 2015). The second

group consists of parents who hold concerns about the safety of vaccines: so-called

‘vaccine hesitators’

(Leask et al., 2012).

2.2.1 Socio-economic disadvantage and logistical barriers

In their analysis of data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC),

Pearce

et al. (2015) found that the majority of incompletely immunised infants (in 2004) did not

have a mother who disagreed with immunisation. Barriers to complete immunisation

identified in the study were: having a larger family (three or more children), moving house

since the birth of the child, less than weekly contact with friends and family, and the use of

formal group childcare. The parents of children who were incompletely immunised had

lower education and income levels.

Ward et al. (2012) also note that certain groups,

including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and those living in socio-economic

disadvantage, were more likely to be incompletely immunised.

Beard et al. (2016) found that partially vaccinated children without a registered

conscientious objection were more likely to be living in areas in the lowest decile of socio-

economic status, ‘suggesting delayed vaccination caused by problems related to

disadvantage, logistic difficulties, access to health services, and missed opportunities in

primary, secondary and tertiary health care’ (p. 275). They also found that children born

overseas were significantly more likely to have neither vaccinations nor an objection

recorded, but acknowledged that they may very well be vaccinated.

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

14

link to page 95 link to page 94 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 94 link to page 94

Gibbs et al. (2015) found that the most commonly reported reason why a significant

minority of children in Western Australia had no vaccination history recorded in the ACIR

was because their families had moved from overseas and their vaccination history had not

been recorded in the ACIR. The second most common reason was that the parents were

unregistered conscientious objectors.

2.2.2 Vaccine hesitancy

Forbes at al. (2015) define vaccine hesitancy as having varying degrees of concerns about

immunisation. They estimate that between 30 and 70 per cent of parents in developed

countries could be categorised as vaccine-hesitant. Reasons for vaccine hesitancy include

religious obligations, safety concerns for children, distrust of government services and

health systems, misinformation or lack of knowledge, and the perceived threat of autism

following vaccinations

(Danchin & Nolan, 2014; Dubé et al., 2016). Despite the empirical

literature reinforcing the benefits and safety of vaccinations, vaccine hesitancy continues to

rise

(Dubé et al., 2016).

Vaccine hesitancy can lead some parents to delay vaccination, to select only the vaccines

they consider safe or to outright refuse to vaccinate. Prior to 1 January 2016, parents who

refused to vaccinate their child could continue to access child care payments if they

registered a ‘conscientious objection’ with DHS (via a recognised immunisation provider).

Parents who chose not to vaccinate and who were ineligible for payments could register an

objection if they wished.

In their analysis of trends and patterns in vaccine objection between 2002 and 2013 as

recorded in the ACIR,

Beard et al. (2016) found that the proportion of children with a

registered objection increased from 1.1 per cent to 2.0 per cent. They found that children

with a registered objection were clustered in regional areas, which they note can pose a

risk of local disease outbreak. They also found that children with a registered objection

were more likely to be living in areas in the highest socio-economic decile than in the

lowest. This implies that financial sanctions, such as the withdrawal of FTB Part A

supplement, are less likely to impact on those with a registered objection than on vaccine

hesitators and those whose children have not been fully vaccinated because of logistical

barriers. However, Child Care Rebate is not subject to a means test, and as such is likely

to have an impact across all socio-economic deciles.

2.3 Increasing immunisation uptake

Improving vaccination uptake is a key policy goal both nationally and globally, with a range

of different approaches adopted with this goal in mind. Measures include: financial

incentives, financial penalties, reminder systems, and effective communication/education

strategies. Often a combination of different approaches is adopted. Much Australian and

international research has sought to evaluate the impact of these approaches on

increasing immunisation rates, with many considering the cost-effectiveness of the

approaches. Prior to considering some of this research, it is important to note that many

authors acknowledge the poor evidence-base for determining the most effective

strategies/interventions for increasing vaccine uptake, and the need for the rigorous

evaluation of any intervention and its impact on vaccine hesitancy/refusal

(Dube, Gagnon,

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

15

link to page 94 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 96 link to page 95 link to page 96 link to page 95 link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 94

MacDonald, & The SAGE Working group on Vaccine Hesitancy, 2015; Leask, Willaby, &

Kaufman, 2014; Williams, 2014).

2.3.1 Financial incentives

Since the

Seven Point Plan, policy makers in Australia have used financial incentives to

increase vaccination rates

(Lawrence et al., 2004; Ward et al., 2013). Although vaccination

rates increased significantly following the introduction of the Plan

(Hull et al., 2013), other

reforms, including educational campaigns, financial incentives for general practitioners and

school/childcare entry requirements, were introduced at the same time. This makes it

difficult to separate the impact of financial incentives on the increase

(Ward et al., 2013).

Neverthel

ess, Ward et al. (2013) argue that they ‘are likely to have made a significant

contribution to increasing childhood immunisation coverage to over 90%’ (2013: 592).

However, overall, there is limited empirical evidence documenting the effectiveness of

financial incentives on vaccination behaviour

(Lawrence et al., 2004; Mantzari, Vogt,

Marteau, & Kazak, 2015).

A perceived risk of incentivising parents to immunise their children by offering a financial

reward is that they may feel more compelled to vaccinate for the financial rather than

health benefits. For this reason, financial rewards are often combined with educational

programs and other interventions aimed at increasing vaccination uptake

(Mantzari et al.,

2015).

2.3.2 Financial penalties

Several studies have examined the effectiveness of financial sanctions on immunisation

rates. In many cases, however, financial sanctions are introduced alongside other

changes, making it difficult to isolate their effectiveness alone.

An Australian study by Lawrence et al. (2004) sought to determine if the risk of financial

sanction influenced parents’ decision to vaccinate. Overall the study found an association

between knowledge of welfare payments and age-appropriate vaccinations. However, it

also highlighted that encouragement from health care professionals was important in the

decision-making process. Among parents whose children were fully immunised, only 4.4

per cent reported that the MIA was the most important influence on their decision to

vaccinate, while for 0.7 per cent of parents, it was the Child Care Benefit (CCB)

(Lawrence

et al., 2004). Roughly two thirds of the parents in the study who received the MIA indicated

that they were vaccine-hesitant. This may indicate that linking welfare payments with

vaccinations may be influential in increasing vaccination uptake amongst this group.

Given the increase in the number of school-age children receiving vaccine exemptions for

non-medical reasons in the United States

, Constable, Blank, and Caplan (2014) argue that

measures that impose a financial cost on vaccine objection ought to be considered

alongside more effective vaccination education in order to increase vaccination rates. They

acknowledge that imposing a financial penalty (e.g. financial incentives in the form of

taxation, health insurance costs, and or private school funding) ‘falls somewhere on the

spectrum between persuasion and coercion’ but argue that the public health benefits

outweigh this imposition on autonomous decision-making.

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

16

link to page 94 link to page 94 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 96 link to page 94 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 95

The use of financial sanctions to encourage vaccination uptake has raised ethical

concerns internationally

(Adams et al., 2016). Concerns relate to the perceived removal of

civil liberties, penalising children for their parents’ decisions, and increasing families’

financial hardship. While financial sanctions can lead to increases in vaccination uptake,

they may also disengage vaccine hesitant parents and health professionals from the

educational process. On the other hand, it could be argued that the public health benefits

of vaccinations may outweigh individuals’ right to decide whether or not they vaccinate

(Adams et al., 2016). The challenge is to find the right balance between the right to

autonomy and the right for safety from vaccine-preventable diseases.

2.3.3 Reminder systems and follow-up

Harvey et al.’s

(2015) systematic review and meta-analysis found that receiving both

postal and telephone reminders was the most effective reminder-based intervention for

increasing vaccination uptake, and that educational interventions were more effective in

low- and middle-income countries. In their systematic review,

Jacob et al. (2016) found

that reminder systems, for clients or immunisation providers, were among the lowest cost

strategies to implement and the most cost-effective in terms increasing immunisation rates.

They found that strategies involving home visits and combination strategies in community

settings were expensive and less cost-effective.

Ward et al.’s (2012) systematic review identified a number of strategies to improve

vaccination uptake that were relevant to the Australian context. Of the strategies reviewed,

catch-up plans showed the greatest impact on immunisation uptake but recall/reminders

for patients and vaccination providers were the most commonly evaluated strategies and

had the strongest evidence.

In the Australian context,

Pearce et al. (2015) argue that greater effort should focussed on

overcoming barriers to immunisation through sending reminders and rescheduling

cancelled appointments or interventions that offer immunisation in alternative settings for

those families that face challenges accessing services.

Given that a high proportion of incompletely immunised children in their analysis had

moved from overseas,

Beard et al. (2016) recommend that primary care clinicians should

focus on both partially vaccinated children and overseas born children. For the latter their

overseas vaccination history should be accurately confirmed by a vaccination provider and

recorded in the ACIR. This is echoed by

Gibbs et al. (2015) who recommend a number of

strategies for addressing the immunisation status and records of families moving from

overseas.

2.3.4 Effective clinician communication

Researchers have emphasised the importance of effective clinician communication for

increasing vaccination uptake.

Forbes, McMinn, Crawford, Leask, and Danchin (2015) differentiate between five groups of parents based on their stance towards immunisation.

These are: unquestioning acceptors, cautious acceptors, hesitant vaccinators, late or

selective vaccinators and refusers. Elsewher

e, Leask et al. (2012) develop a framework to

assist clinicians in communicating effectively with these different groups of parents to

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

17

link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 94 link to page 95 link to page 96 link to page 96

enable them to make informed decisions about vaccination. In emphasising the centrality

of effective clinician-parent dialogue, regardless of the parent's stance towards

immunisation, Leask et al. advocate for ‘an approach to communication that encourages

questions and employs a guiding rather than directing style’.

In advocating for the need for ‘new approaches to vaccine consultation’

, Leask and

Kinnersley (2016) argue that physicians need to have the opportunity to engage with

vaccine-hesitant parents in order to address any concerns they might have. They

acknowledge that physicians are generally unable to devote adequate time to undertake

training in communication interventions, and suggest that decision aids that ‘are designed

to help people understand their options and potential outcomes, to consider the possible

benefits and harms of their choices, and to increase consumer participation in decision-

making’ might prove useful in the context of vaccine hesitancy. They argue that it is critical

that funding is directed towards developing ‘conceptually clear, evidence informed, and

practically implementable approaches to parental vaccine hesitancy’.

Elsewher

e, Leask (2015) argues against an adversarial approach to increasing vaccination

rates, because it draws attention to vaccination objectors and their arguments and has the

potential to alienate vaccine-hesitant parents. Instead, she argues that advocacy and

policies should address the factors that influence the low uptake of vaccines.

Leask et al (2014)'s article on vaccine hesitancy outlines a number of strategies that are

required in order to address vaccine hesitancy. These include: the identification and testing

by governments and research agencies of interventions designed to increase uptake of

vaccines among vaccine-hesitant parents; monitoring vaccine acceptance; community-

level responses to engage communities in dialogue (as vaccination rejection or hesitancy

is often a community-based phenomenon); provider-level solutions as interaction between

parents and providers can influence uptake, however the evidence-base is limited; and

provider education – vaccination providers ought to have a good understanding of

vaccines and vaccine hesitancy. Addressing vaccine hesitancy requires ‘political will,

professional commitment, and research investment in order to develop and evaluate new

and innovative solutions’ (p. 2601).

The extant evidence suggests that the most effective interventions for increasing

vaccination rates involve multi-component strategies which generally include educational

programmes and interventions which aim to address logistical barriers to immunisation

(Dube et al., 2015; Jarret, Wilson, O’Leary, Eckersberger, & Larson, 2015; Pearce et al.,

2015). Because most interventions include several components, it is often difficult to

determine which component or combination of components leads to an increased

vaccination uptake. As there are multiple population groups who do not fully vaccinate their

children, with different drivers for each group, it is likely that no single measure – or type of

measure – will address the needs of all these groups, and that multi-component strategies

will need to specifically target conscientious objectors, vaccine hesitators and those who

face logistical barriers to having their children vaccinated.

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

18

link to page 95 link to page 96 link to page 94

2.4 The No Jab No Pay budget measure

On 12 April 2015, the Measure was announced by the Hon Scott Morrison MP, the then

Minister for Social Services and the then Prime Minister the Hon Tony Abbott MP. The

Measure was a pre-budget Government announcement and was included in the 2015–16

Australian Government Budget. From 1 January 2016, the Measure was implemented by

the Australian Government. There is as yet no available research evidence about the

impact of the Measure on immunisation rates; however, some commentary on the

Measure appeared shortly after its announcement in 2015.

In an opinion piece in the Australian Medical Association's (AMA) publication

Australian

Medicine, Macartney (2015) of the National Centre for Immunisation Research &

Surveillance argues that there are better ways to improve vaccination rates than imposing

financial penalties on parents. She asserted that the Measure is 'unnecessarily punitive

and could have negative repercussions' and that there are alternative means of increasing

the immunisation rate. These include: reminding and supporting parents to immunise;

improving access, awareness and the affordability of vaccination; enabling vaccine-

hesitant parents to engage with qualified health professionals; and grassroots campaigning

for immunisation that promotes immunisation as part of a healthy lifestyle.

In the

Australian Medicine Budget edition (14 May 2015),

Rollins (2015) highlighted the

AMA’s concern about the projected savings to government of over $500 million by 2018–

19 from the Measure, because families will be ineligible for child care payments and family

tax benefits. Rollins quotes the President of the AMA as stating that the aim should be to

invest the money saved on increasing vaccination rates.

While some external stakeholders focussed on the perceived savings, the Government

made it clear that the purpose of the Measure was to improve immunisation rates, not

budgetary savings

(Abbott, 2015). These concerns, and the lack of empirical evidence in

Australia and internationally about the effectiveness of different strategies to increase

vaccination rates, make it imperative that the Measure should be comprehensively and

independently evaluated to examine its impact on different population groups in the short,

medium and longer term.

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

19

link to page 22

3 Methodology

The No Jab, No Pay Post Implementation Review was guided by several key questions

listed below. As shown in

Table 1 the methodology drew upon different methods of data

collection to address each question.

Table 1 Research areas, questions and data sources

Research questions

Data sources

Policy design

1. Has implementation been consistent with the Measure's policy design?

Document review

2. If there have been any deviations from the original design, have these been

Stakeholder

positive or negative in nature?

consultations

Data scoping

Issues and risks

1.

Stakeholder

What successes and challenges (including design, system, data,

consultations

communications, and uptake of immunisation by the target populations) were

encountered in implementing the Measure?

Document review

Governance

1. Did governance and decision-making mechanisms help or hinder the successful Stakeholder

implementation of the Measure?

consultations

Document review

Service delivery

Stakeholder

1. Has the service delivery model resulted in impacted recipients having positive

consultations

or negative encounters?

Communications

Stakeholder

1. Did the communication strategy and Departmental communication plans

consultations

successfully support the implementation of the Measure?

2. Did the Communication Working Group effectively manage communication

Document review

issues as they arose?

Management information

Data scoping

1. How has the policy and system design impacted upon the data available to date

regarding rates of immunisation and eligibility for both family assistance (Family

Stakeholder consultation

Tax Benefit Part A supplement) and child care payments?

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

20

3.1 Document review

The document review involved a review of publicly available and internal government

documents. The Department of Social Services (DSS) provided the research team with

documents and web links under the following headings:

• Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee Inquiry

• Reports and Project Plans

• Fact sheets and schedules

• Policy resources

• Legislation

• Data sets

• Communications

• Letters to recipients

• No Jab, No Pay Interdepartmental Committee and Working Group papers.

These documents were imported into the qualitative software NVivo where they were

coded and reviewed.

3.2 Data scoping

The review of the datasets involved a data scoping exercise that provided the research

team with an understanding of the quality of data available and the degree to which it may

be useful for inclusion in the subsequent impact evaluation. The review did not involve any

analysis of the available data. The data scoping encompassed a review of four data

sources, as advised by the DSS: the ACIR/AIR, Child Care Management system, Day One

implementation reports and data from the Enterprise Data warehouse in DHS. Discussions

about the data items, data quality, data linkage processes and departmental processes for

data access for external researchers were conducted with key contacts from DSS, DHS,

DET and ACIR/AIR. Data dictionaries were requested in all cases and provided by DHS.

3.3 Qualitative stakeholder consultation

A component of the PIR involved consultation with key staff in the four government

departments (DSS, Health, DHS, DET) involved in the implementation of the Measure and

with stakeholders from organisations external to the Australian Government. Fifteen staff

members from the four government departments and eight external stakeholders were

invited to participate in semi-structured interviews. Ethics approval for the PIR was given

by the UNSW Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC No. HC16563) and

participation in the research was voluntary.

Nine government stakeholders were interviewed from DSS, Health, DHS, DET. These

stakeholders were from a range of areas within these departments, including payment

policy and operations, immunisation policy and programs, database management, and

communications. In addition, nearly all of these stakeholders were involved with both the

Working Group and the Interdepartmental Committee. Most had also been involved in the

design and development of the policy prior to its implementation.

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

21

link to page 96

In addition to the government stakeholder cohort, eight external stakeholders were

interviewed. These external stakeholders were from organisations external to the

Australian Government, with four representing state-based health service providers, two

representing a not-for-profit early learning provider, one representing a peak body, and

one academic. As such, their perspectives differed from those of the government

stakeholders as they had less of an ‘internal’ view of the implementation and more of an

‘on the ground’ view, allowing them to comment on the effects of the Measure on

immunisation providers and recipients. The interviews were conducted over the phone and

recorded with participants’ consent.

It is important to emphasise that the views gathered through the stakeholder consultation

are not necessarily representative of all individuals involved in the implementation of the

Measure. Rather, qualitative studies typically select information-rich cases for in-depth

study ‘from which one can learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the

purpose of the research’

(Patton, 1990, p. 169) without making claims to be representative

of a larger population. For the purpose of the PIR, the aim of the stakeholder consultation

was to canvass a range of views and perspectives on the successes and challenges of

implementing the Measure. A further aim of the consultations was to identify any issues

that stakeholders felt should be considered for any impact evaluation of the Measure.

3.4 No Jab, No Pay workshop

The research team facilitated a workshop with 16 stakeholders in DSS National Office in

November 2016. Workshop attendees included a range of participants from the four

departments responsible for policy implementation, including individuals with knowledge of

the relevant databases. The workshop provided the opportunity to present the findings of

the PIR, including the program logic and theory of change, and the preliminary impact

evaluation framework. Workshop attendees were invited to provide feedback on the

material presented, and the research team followed up with a number of staff following the

workshop to clarify issues and source additional documentation.

3.5 Analysis and synthesis of findings

The analysis involved triangulation of data, including the review of policy documentation,

and insights from the data scoping exercise and from the qualitative data collected.

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

22

link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 94 link to page 94 link to page 94 link to page 94

4 Findings

This section presents the findings of the PIR as they relate to the key research questions.

4.1 Policy Design

The PIR was guided by two key questions with respect to policy design:

•

Has implementation been consistent with the Measure's policy design?

•

If there have been any deviations from the original design, have these been

positive or negative in nature?

To address these questions, we first review the policy design.

Australian Government child care payments (currently called Child Care Benefit (CCB) and

Child Care Rebate (CCR)) have been linked to immunisation status since 1998. Since

2012, payment of Family Tax Benefit (FTB) Part A supplement was also linked to

immunisation status at certain ages. Although these payments were linked to immunisation

status, parents could access CCB, CCR & FTB Part A supplement if they registered a

conscientious objection (CO) to having their child immunised.

On 23 November 2015, the No Jab, No Pay 2015–16 Budget measure was passed in the

Social Services Legislation Amendment (No Jab, No Pay) Act 2015 (Parliament of

Australia, 2015).

The goals of the Measure were to:

•

‘reinforce the importance of immunisation and protecting public health by

strengthening immunisation requirements for children’

(Department of Social

Services, 2016, p. 1)

•

‘amend the immunisation requirements that apply to Australian Government child

care payments and the FTB Part A supplement’.

(Department of Social Services,

2016, p. 1).

While the Measure was expected to save over $500 million over three years, these

savings were not the intended goal of the Measure.

Implementation of the Measure required activation of three separate mechanisms in

addition to other related measures/legislation. The three mechanisms outlined in the

legislation were: a modification of existing exemption categories; extending eligibility

monitoring; and changes to the existing grace period for children who were not up to date

with immunisations. These legislative changes were put into effect through DHS systems.

Associated measures and legislative changes (described further below) were:

•

the expansion of the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR);

•

Vaccination Providers who administer and report catch-up vaccinations for children

up to 7 years of age) who are more than two months overdue and who receive all

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

23

link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 95 link to page 94

scheduled vaccines at that scheduled point (2, 4, 6, 12, 18 months and 4 years of

age) can receive a catch-up notification payment; and

•

free ‘catch-up’ vaccines for individuals aged 10 up to 20 years and who are in

receipt of family payments.

In addition, legislation in New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria introduced ‘No Jab

No Play’ requirements, restricting access to child care centres for children who are not

immunised.

The Australian Government has also proposed phasing out of the FTB Part A end of year

supplement, which would also impact on the No Jab, No Pay measure.

4.1.1 Exemption categories

Prior to the introduction of the Measure, parents could continue to access child care

payments and FTB Part A supplement if their child was not up to date with their

immunisations if the parent completed an

Immunisation exemption conscientious objection

form with a recognised immunisation provider and registered their objection with

ACIR/AIR. Exemptions had also been granted on religious grounds to children of members

of the Church of Christ, Scientist. With the introduction of the Measure, these two

exemption categories were removed. As a result, from 1 January 2016, parents who

registered as conscientious objectors or as members of the Church of Christ, Scientist

were no longer eligible for child care payments and FTB Part A supplement if their child

was not up to date with their immunisations or on a catch-up schedule. Exemptions still

remain for children with a medical contraindication, with natural immunity or who are

participating in a vaccine study

(Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee, 2015,

pp. 2-3).

The

Social Services Legislation Amendment (No Jab, No Pay) Act 2015 (Parliament of

Australia, 2015) repealed Section 7 of the

A New Tax System (Family Assistance) Act

1999 (Parliament of Australia, 1999) which provided that the ‘Minister may make

determinations in relation to the immunisation requirements’. Instead a new section 6(6)

was included that provides that a child meets the immunisation requirements if the

Secretary determines that the child meets the requirements. The Act provides, in section

6(7) that the Secretary must comply with any decision-making principles set out in a

legislative instrument made by the Minister, for the purposes of that subsection. Currently,

the

Family Assistance (Meeting the Immunisation Requirements) Principles 2015

(Australian Government, 2015b) allow the Secretary to make such a determination

in the

following circumstances:

•

if the child is under 15 years of age, a person with legal authority to make decisions

about the medical treatment of the child has refused, or failed within a reasonable

time to provide consent or, if the child is aged at least 15 years of age, the child has

refused, or failed within a reasonable time, to provide consent to be immunised

•

if

there is a risk of family violence if action is taken to meet immunisation

requirements

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

24

link to page 94

•

if the parent becomes a permanent humanitarian visa holder within 6 months of the

child’s arrival to Australia

•

if the child is vaccinated outside of Australia and certified by a medical practitioner

in respect of the FTB Part A Supplement only

•

if the child is at a heightened risk of serious abuse or neglect if the Secretary does

not make a determination that the child meets the immunisation requirements in

respect of child care payments only.

4.1.2 Eligibility monitoring

Previously eligibility was checked against immunisation requirements at ages 1, 2 and 5

for FTB Part A supplement and each year up to age 7 for child care payments. With the

introduction of the Measure, eligibility for all payments will be checked against

immunisation requirements each year until the child is aged 20 years (Senate Community

Affairs Legislation Committee, 2015: 3).

4.1.3 Changes to the 63 day grace period

Previously, a 63-day grace period was available for children to commence a catch-up

schedule if they did not meet the immunisation requirements when the individual first

attempted to claim child care payments. During this initial grace period, parents could

access child care payments. With the introduction of the Measure, this initial grace period

has been removed for new claimants, and the immunisation requirements must be met in

order for an initial CCB claim to be approved. Grace periods still apply if a child

subsequently stops meeting the requirements, in which case parents are notified and

advised to take steps to bring the child back up to date or risk having child care payments

cancelled.

4.1.4 Other related measures/legislation

Implementation of the Measure also required the introduction of additional measures and

legislative changes. These were: the expansion of the ACIR, ‘catch-up’ notification

payments, and the provision of catch-up vaccines for individuals aged 10 to 20 years of

age for eligible recipients.

Expansion of the Australian [Childhood] Immunisation Register

The expansion of the ACIR was the responsibility of Health. The ACIR, renamed the AIR

from 30 September 2016, was expanded in order to record vaccination information for

people up to 20 years of age in order to facilitate the extension of eligibility monitoring for

payments

(Department of Social Services, 2016, p. 2). The legislative changes were

outlined in the

Australian Immunisation Register Act 2015 and

Australian Immunisation

Register (Consequential and Transitional Provisions) Act 2015.

The

Project Management Plan Extending Immunisation Requirements, Project

Management Framework developed by DHS Services (April 2015) refers to the extension

of the ACIR to include the immunisation records for children up to 20 years. ICT system

changes required were: ‘Full end to end system solution to support implementation of the

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

25

link to page 94 link to page 94 link to page 94 link to page 60 link to page 94 link to page 94

policy change across the Centrelink master programme and Medicare master programme,

as well as datalink between the ACIR and ISIS systems’. From an implementation

perspective, recognised constraints included:

• the existing ICT systems had to be used to deliver the business solutions

• ICT capacity and ICT knowledge of ISIS/ACIR systems could affect the program.

Concerns were expressed about the completeness of ACIR records prior to the

implementation of the Measure in submissions to the Senate Community Affairs

Legislation Committee Inquiry into the

Social Services Legislation Amendment (No Jab, No

Pay) Bill 2015. In terms of the expansion of the register, there were a range of concerns

and issues listed in the issues log relating to data quality, including the software used by

some immunisation providers and cases of Immunisation History Backlog in some states

and territories.

‘Catch-up’ immunisation arrangements

In preparation for the introduction of the Measure, arrangements were made to try to

ensure that children who were incompletely immunised could commence a catch-up

schedule and thereby meet/continue to meet eligibility for CCB, CCR and FTB Part A

Supplement payments. The arrangements included:

• extending eligibility for free National Immunisation Programme (NIP) vaccines to all

children under 10 years of age

• the funding of a new catch-up scheme for children aged 10 to 20 years and the

provision of free vaccines to existing CCB, CCR and FTB Part A recipients

(receiving payments on 31 December 2015). This catch-up scheme is available

until 31 December 2017

(Department of Social Services, 2016, p. 2). A document

outlining the processes involved in extending immunisation requirements to

children over 10 years of age was developed by the DHS

(Australian Government,

2015a).

An NIP information update for vaccination providers produced by Health reported that DHS

would inform families if their child did not meet immunisation requirements for family

assistance payments, and that families would be encouraged to speak to a vaccination

provider about updating their records or commencing a catch-up schedule (see Section

4.6.3). The information update also indicated that Health would provide general

practitioners and other immunisation providers with information about the catch-up

immunisation schedule, how to check a child’s immunisation history, how to order vaccines

and how to update immunisation records in ACIR

(Australian Government, no date). A

factsheet for vaccination providers outlining the new immunisation requirements for family

assistance payments was also developed by Health

(Australian Goverrment, 2015).

Incentive payment scheme for general practitioners and immunisation

providers

Although not part of the Measure, a $26 million measure titled

Improving Immunisation

Coverage Rates was announced in the 2015–16 Budget. This additional funding was used

to fund an incentive payment scheme to encourage general practitioners and other

Social Policy Research Centre 2017

26

link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 96 link to page 95 link to page 95

immunisation providers to identify and immunise children up to 7 years of age in their

practice who were more than two months overdue for their vaccinations. The $6 incentive

payment was in addition to the existing $6 that vaccination providers receive to deliver the

vaccination. The funding was also used to ‘improv[e] public vaccination records and

reminder systems; greater public awareness of the benefits of vaccinations; and the

Government’s already announced “no jab, no play, no pay’ policy”’

(The Hon Sussan Ley

MP, 2015).

Phasing out of FTB Part A supplement

Legislation was introduced to the House of Representatives seeking to gradually phase out

the FTB Part A supplement by 2018

(Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee,

2015, p. 3). With the proposed cessation of this payment, it would only operate as a policy

lever to increase vaccination rates in the short-term. This legislation has not yet passed,

however, on 31 August 2016, the Government introduced an income limit for FTB Part A

supplement. From the 2016–17 entitlement year the FTB Part A supplement will be limited

to families with an adjusted taxable income of $80 000 or less

(Parliament of Australia,

2016). However, the Child Care Rebate is not subject to a means test, and as such is likely

to have an impact across all families with children in child care, regardless of family

income.

Related state legislation

Three of the states – New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria – enacted legislation

relating to children’s immunisation status and attendance at childcare and preschool,

known as ‘No Jab, No Play’ policies

(National Centre for Immunisation Research &