FOIREQ20/00232 - 001

Commissioner brief: Budget and resourcing

KEY MESSAGES

•

The OAIC incurred a $0.121mil ion financial loss in 2019-20

1

•

Total revenue, including MOUs, for 2019-20 was $23.234mil ion

•

Total revenue, including MOUs, for 2020-21 is $23.271mil ion

•

2020-21 ASL cap is 124 – actual ASL at 1 October 2020 is 112.

CRITICAL FACTS

•

OAIC incurred a total (permitted) financial loss of $0.121million in 2019-20.

o 2019-20 total revenue was $23.234mil ion — $20.941mil ion is appropriation,

$2.323mil ion is MOU and $36,000 received benefit for annual ANAO financial

audit

2.

•

2019-20 Budget al ocated $25.1 mil ion over three years (including capital funding of

$2.0 mil ion) to facilitate timely responses to privacy complaints and support

strengthened enforcement action in relation to social media and other online

platforms that breach privacy regulations

o 2019-20 Budget al ocated $329,000 to the 2018-19 base and $2.256mil ion over

the forward estimates for oversight of the expansion of Medicare data matching.

o 2020-21 total revenue is $23.304mil ion. $20.948mil ion is appropriation and

$2.323 mil ion is MOU

•

OAIC has not received additional resourcing for the Notifiable Data Breach Scheme (in

2018/19, 2019/20 or 2020/21).

•

OAIC has not received additional funding for its COVID Safe App regulatory role.

•

The OAIC did receive $12.911mil ion over forward estimates for Consumer Data Right

Scheme (

CDR) in the

2018-19 Budget (including a once-off capital injection for new

office space of $860,000). This is approximately $3,000,000 each year. (terminates

fol owing 2021-2022)

•

s74

External revenue (MOU) increased from $2.257m in 2019-20 to $2.323m in 2020-

21. The increase relates to the MOU with Department of Home Affairs relating to

National Facial Biometric Capability.

1 OAIC Underlying Operating Result is a surplus of $0.501 million. This is adjusted by deducting depreciation and amortization

and adding the principal payment on lease liability leading to a loss of $0.121 Million. The outcome that appears in the audited

financial statements and annual report is the loss of $0.121 million.

2 A year end external audit is undertaken by ANAO for FREE, however for accounting purposes we need to recognize it as if it

paid for. So our expenses include $36K for audit expense and to offset this we have $36,00 as ANAO revenue. This is called a

‘received benefit’.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 002

• In the forward estimates, MOU value is $75,000 in 2021-22 and nil after that. This is

due to several MOUs (including ADHA at $2.070mil ion) terminating at 30 June 2021

and yet to be renewed.

POSSIBLE QUESTIONS

Why did OAIC have a surplus in its underlying operating result3?

• Total loss is $0.121mil ion, including depreciation and amortisation and the principal

lease payment.

o The OAIC is permitted to have a loss up to $622,000. This is the value of

depreciation and amortisation, less the principal payment on lease liability.

• However, the OAIC Underlying Operating Result is a surplus of $0.501 mil ion. This is

adjusted by deducting depreciation and amortization and adding the principal

payment on lease liability leading to a loss of $0.121 Mil ion. The outcome that

appears in the audited financial statements and annual report is the loss of $0.121

mil ion.

• The Underlying Operating Result (surplus) is the result of the impact of COVID-19.

Specifical y, both the review of the

Privacy Act 1988 and the development of the

Online privacy code were delayed as a result of the pandemic. The OAIC’s planned

recruitment activity was delayed and international and domestic travel halted also as

a result of the pandemic. These initiatives are expected to recommence in the

2020/21 financial year.

Did the OAIC receive additional resources for the Notifiable Data Breaches scheme or the

COVIDSafe App?

No, there were no additional resources provided for either function, work is prioritised

within the existing resource al ocation.

What activities will you undertake with the increase of funding by $25.121million

al ocated for over three years commencing in the 2019-20 Budget to undertake regulatory

functions, including regulating the handling of personal information and taking

enforcement action?

The OAIC continues to undertake careful planning to ensure that we identify the

components of each of the new functions, consider sequencing and recruit people with the

right skil set to deliver them. The OAIC’s average staffing level increased from 85 in June

2019 to 95 by June 2020 to 112 at 1 October 2020.

Does this funding include an allocation for freedom of information?

No. The funding is for privacy functions. The office continues to look for and implement

opportunities to increase productivity in relation to its freedom of information regulatory

functions. There has been an increase of 72% in the number of IC reviews finalised by the

OAIC between 2014-15 and 2019-20. However, it remains the case that although

3 Senators will not have the Underlying Operating Result figure from the annual report. However, it is possible they may

understand the financial approach and determine that there was a surplus or question the outcome.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 003

demonstrated significant efficiencies have been found and applied, the function output has

not kept pace with incoming IC reviews, FOI complaints, extension of time applications and

applications for vexatious applicant declarations complaints and decision reviews. There has

been a 186% increase in Information Commissioner reviews received between 2014-15 and

2019-20.

What activities are you undertaking with the increased of funding for Medicare data

matching?

Enquiries, complaints, conciliation, investigation, CI s, assessments.

The funding enables the OAIC to undertake two privacy assessments (audits) per year to

proactively monitor whether information subject to the new arrangements is being

maintained and handled in accordance with the relevant legislative obligations and

recommend how areas of non-compliance can be addressed and privacy risks reduced.

Funding for Expanding Digital Identity commences in 2021-22. Are you required to

undertake any activities this financial year and what will you do with the funding next

financial year?

The OAIC is not receiving funding for activities in relation to this project in 2020-21,

however we wil continue to undertake our normal monitoring and guidance-related

functions to help ensure that the expansion of the scheme includes appropriate privacy

protections and aligns with the objects of the Privacy Act.

The funding in 2021-22 wil enable the OAIC to undertake two privacy assessments (audits)

to proactively monitor the privacy protections built into the Digital Identity program, which

wil assist the Digital Transformation Authority to mitigate privacy risks with the system.

This funding also includes provision for the OAIC to develop two or three pieces of guidance

about the privacy aspects of the Digital Identity system.

Will the growing workload result in greater backlogs?

The OAIC continues to implement efficiencies in the way work is completed. For example,

the OAIC recently reviewed its workflow processes for the Dispute Resolution Branch to

streamline the complaint handling process. The OAIC continues to look for and implement

opportunities to further improve productivity to address the increasing volume of incoming

work, within the resources available to us, and to prioritise as appropriate.

However, efficiencies cannot currently keep pace with the continuing rise in incoming FOI

work.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 004

KEY DATES

• 22 February 2018: NDB Scheme commenced, no additional funding received.

• 1 July 2018: 2018-19 Budget provides $12.91mil ion over the forward estimates for

CDR

• 30 June 2019:

Enhanced Welfare Payment Integrity – non-employment income data

matching (commenced MYEFO 2015-16) measure valued at $1.326mil ion terminates.

• 1 July 2019: 2019-20 Budget provides $25.121mil ion over three years to enhance

funding for statutory obligations and social media.

• 1 July 2019: 2019-20 Budget provides $329,000 to the 2018-19 base and $2.256mil ion

over the forward estimates for the expansion of Medicare data matching.

• 24 June 2020: MOU funding with ADHA secured at $2.070mil ion for one year.

• 1 July 2023: reduction in revenue due to terminating measure (statutory obligations

and social media).

• 1 July 2021: 2021-22 Forward Estimates provides $0.261mil ion for Expanding Digital

Identity

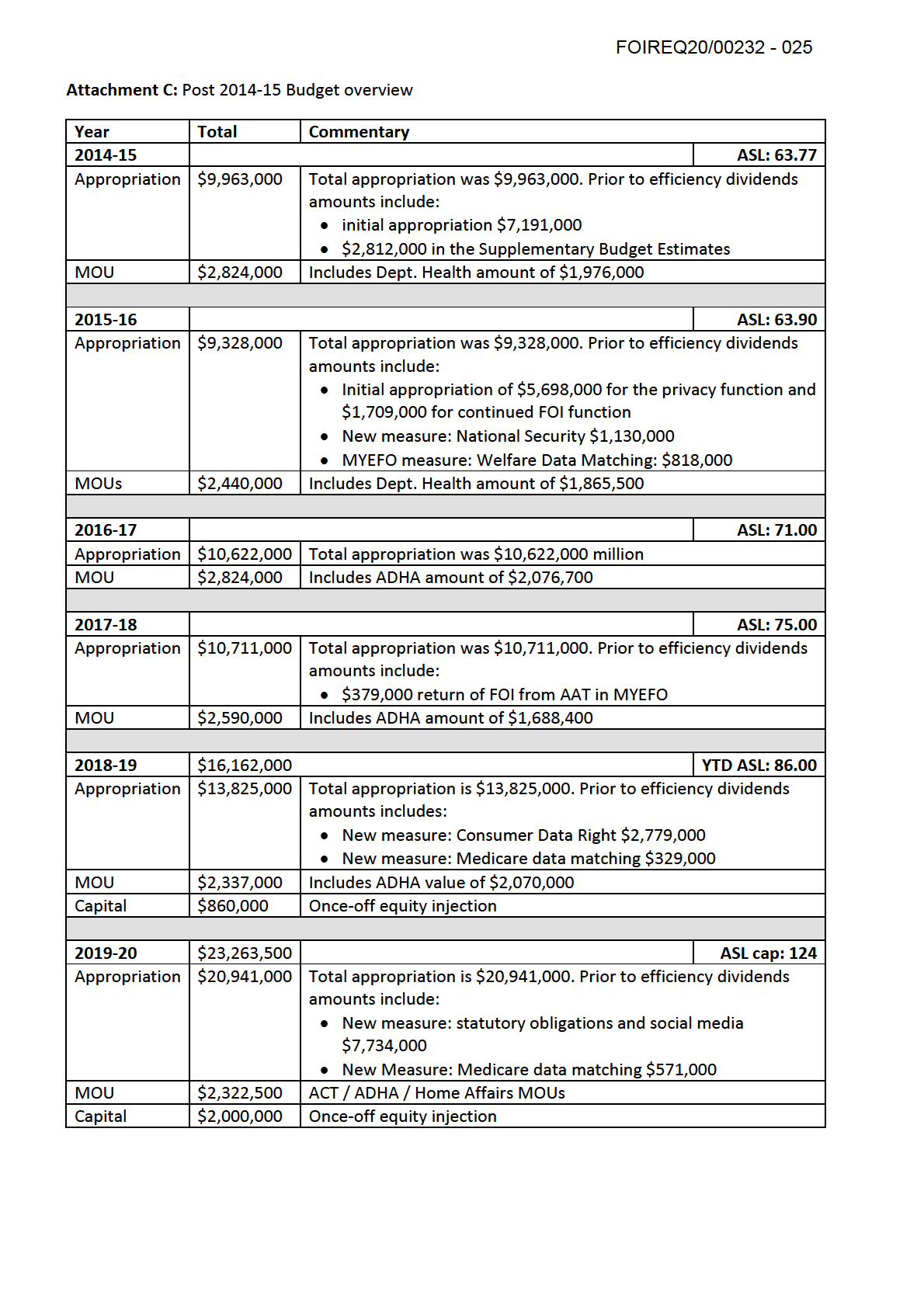

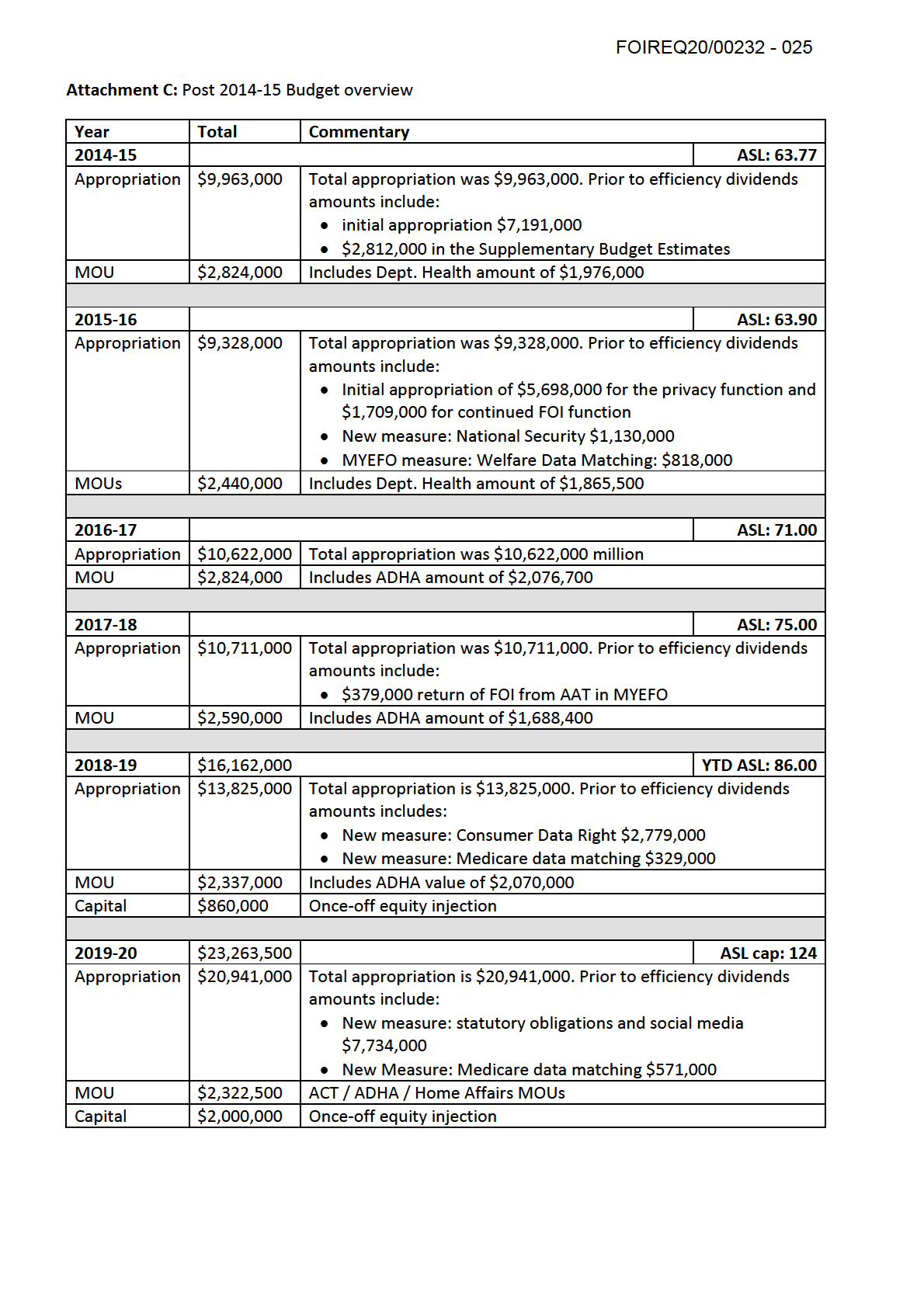

FORWARD ESTIMATES

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

2022-23

2023-24

Appropriati

$20,941,00 $20,948,000

$20,711,000 $13,039,000 $13,089,000

on

0

MOUs

$2,257,000 $2,322,500

75,000

—

—

Total $23,198,00 $23,270,500

$20,786,000

$13,039,000

$13,089,000

0

Difference from prior year

+$72,500

-$2,484,500

-$7,747,000

+$50,000

FOIREQ20/00232 - 005

MOU detail

MOU

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

ADHA

2,070,000

2,070,000

—

ACT

$177,500

$177,500

—

Government

USI

—

—

—

DHA – NFBMC

—

$75,000

$75,000

Other revenue

$9,500

—

—

Total $2,257,000

$2,322,500

$75,000

Statutory obligations and social media detail

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

2022-23

Appropriation

$7,734,000

$7,887,000

7,500,000

—

Capital

$2,000,000

—

—

—

Total

$9,734,000

$7,887,000

$7,500,000

—

Medicare data matching

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

2022-23

Appropriation

$571,000

$565,000

$560,000

$560,000

Capital

–

—

—

—

Total

$571,000

$565,000

$560,000

$560,000

CDR detail

2018-19

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

2022-23

Appropriation

$2,779,000

$3,178,000

$3,036,000

$3,058,000

Not

identified

Capital

$860,000

—

—

—

–

Total

$3,639,000

$3,178,000

$3,036,000

$3,058,00

Expanding Digital Identity

2018-19

2019-20

2020-21

2021-22

2022-23

Appropriation

—

—

—

$261,000

—

Capital

—

—

—

—

—

Total

—

—

—

$261,00

—

FOIREQ20/00232 - 006

2020-21 FUNDING

•

2020-21 total revenue is $23.270mil ion, of this:

o $20.948mil ion is appropriation (including $7.887mil ion for social media &

$3.036 mil ion CDR & $0.565mil ion for Medicare data matching)

o $2.322mil ion is MOU based.

2019-20 OPERATIONAL PROFIT

Item

Amount

Note

Depreciation &

$2,234,000

Permitted loss amount

amortisation

Principal Payment of

$1,612,000

Permitted loss amount

Lease Liabilities

Unforeseen

$501,000

This surplus is the result of the impact of

underspend

COVID-19. Specifical y, both the review of

the Privacy Act 1988 and the development

of the Online privacy code were delayed as

a result of the pandemic. The OAIC’s

planned recruitment activity was delayed

and international and domestic travel

halted also as a result of the pandemic.

These initiatives are expected to

recommence in the 2020/21 financial year

Total Deficit per

$121,000

statutory financial

accounts

2020-21 ASL

• OAIC’s permitted ASL cap is 124 including:

o 23ASL for statutory obligations and social media

o 15ASL for CDR

o 3 ASL for Medicare data matching

As at 1 October 2020

• Year-to-date ASL at 1 October 2020 is 112

• Year-to-date FTE at 1 October 2020 is 116 (detailed below)

• Current recruitment agency staff at 1 October 2020 is 6

FOIREQ20/00232 - 007

• Full-time-equivalent (FTE) at 1 October 2020 is 116. That FTE is allocated to:

1 October 2020 20 February

2 October 2019 20 March 2019

2020

OAIC

116 FTE

94 FTE

99 FTE

86 FTE

Privacy

76 / 65%

64 / 69%

65 / 66%

59 / 68 %

(including NDB)

NDB

5 / 7%

3 / 5%

4 / 11%

7 / 8%

(included in

privacy)

FOI

25 / 22%

18 / 19%

20 / 20%

20 / 24 %

Governance & 15 / 13%

11 / 12%

14 / 14%

7 / 9%

support

• Refer to Attachment

A for excerpts of previously quoted ASL/FTE figures

BACKGROUND

• Attachment A: Excerpts — previously quoted ASL/FTE figures

• Attachment B: Background on MBS / PBS

• Attachment C: provides overview of the OAIC’s budget from 2014-15 onwards

DOCUMENT HISTORY

Updated by

Reason

Approved by

Date

Mario Torresan October 2020 Estimates

FOIREQ20/00232 - 008

Attachment A: Background on MBS / PBS

What is the Guaranteeing Medicare – improving safety and quality through stronger

compliance measure?

In May 2018, the Government announced an investment of $9.5 mil ion over five years

from 2017-18 to continue to improve Medicare compliance arrangements and debt

recovery practices to ensure Medicare services are targeted at serving the health needs of

Australian patients. This measure includes better targeting investigations into fraud,

inappropriate practice and incorrect claiming and wil use data analytics and behavioural

driven approaches to compliance.

Did the OAIC receive additional resources for the regulatory oversight of a revised

MBS/PBS scheme?

Yes. The OAIC received funding of $2.256 mil ion over the forward estimates years from

2019-20.

What activities wil you undertake with increase of funding for regulatory oversight of a

revised MBS/PBS scheme?

The OAIC wil be the complaint handling body for the regime, and wil offer the mechanism

through which consumers can seek a formal remedy to redress a breach of their privacy;

and respond to general enquiries from the community. This includes investigating and

taking enforcement action in relation to breaches of the scheme, including the conduct of

Commissioner-Initiated Investigations

The funding wil also enable the OAIC to undertake two privacy assessments (audits) per

year to proactively monitor whether information subject to the new arrangements is being

maintained and handled in accordance with the relevant legislative obligations, and

recommend how areas of non-compliance can be addressed and privacy risks reduced.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 009

Attachment B: Excerpts — previously quoted ASL/FTE figures

Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee

03/03/2020

Estimates

ATTORNEY-GENERAL'S PORTFOLIO

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner

[21:47]

Senator PATRICK: Thank you for coming along tonight, Ms Falk. I just want to know whether you

could provide the committee with some information in relation to an investigation you conducted into

the Prime Minister's office in respect of FOI performance.

Ms Falk

: Yes, Senator.

Senator PATRICK: There was an article in the

Guardian that talked about you having conducted a

review or an examination into the Prime Minister's office. I don't want to rely on the media. I just

would like a summary of your findings in relation to that.

Ms Falk

: Under the FOI Act I have a statutory requirement to investigate complaints that are made

to my office regarding the processing of FOI matters. This complaint was lodged with my office in

2018. The complaint progressed. It contained allegations of delay in relation to that particular

department in relation to the complainant. There's a process that's undertaken in terms of receiving

submissions and analysing the information. Then it falls to me to make investigation findings. In this

matter, I concluded that there had been a delay without authorisation under the FOI Act. I can then

make remedial recommendations to the agency.

Senator PATRICK: This was only related to one FOI?

Ms Falk

: It was. In relation to the matter, I made recommendations. In relation to that particular

department, they had been experiencing delays overall with their processing of FOI matters. In the

2018-19 financial year 72.6 per cent of all requests determined by the department were in time, which

was a considerable improvement on the year before, at 35.5 per cent. I made four recommendations to

the department and those recommendations were accepted by the department. I also asked for a

report to be provided to me in relation to the implementation of the recommendations. I received that

just last week and it is under consideration by my office.

Senator Payne: Just to be clear, Ms Falk: we're talking about the Department of the Prime Minister

and Cabinet, aren't we?

Ms Falk

: Yes, we are.

Senator Payne: So it's not the Prime Minister's Office, but the department.

Senator PATRICK: Okay, I apologise for my clumsiness.

Senator Payne: No, just clarifying.

Senator PATRICK: Thank you, Minister. I will say that I did ask questions about this and they

indicated that they are now at 100 per cent compliance. So it looks like you may have done some good

work on that, Commissioner.

Ms Falk

: It's a very pleasing result.

Senator PATRICK: Can you provide an update on your investigation into Home Affairs?

Ms Falk

: That matter remains ongoing. We have been working with the Department of Home Affairs,

who have been very cooperative with the investigation. We have requested information from them and

considered it, and we will be requesting further information. The matter is one that is under active

consideration by the office.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 010

Senator PATRICK: I was involved in a discussion with a constituent last week who said they had

not received a response in over a year in relation to an FOI request. I'm not raising a complaint with

you; I'm just wondering whether the scope of your current inquiry is likely to capture that sort of

circumstance.

Ms Falk

: The current investigation is in relation to the Department of Home Affairs' processing of

non-personal information requests—so, other information—which is a much smaller cohort of the

overall 17,000-plus requests that Home Affairs receives each year. But it is the area where timeliness

seemed to be most acute, so whether the matter would be raised within its scope would depend on the

particular nature of your constituent's issues. The scope of the investigation will be looking at issues of

the timeliness for non-personal information and the processes in place to deal with those requests. At

the conclusion of the investigation it is open to me to make recommendations to the agency head.

Senator PATRICK: You might find a couple of my FOI requests in there that weren't answered

within the time frame!

Senator Payne: Surely not!

Senator PATRICK: In relation to my constituent, what's your recommended course of action in

relation to an FOI that hasn't been responded to in over a year? Is it best to simply contact your office

to make a complaint, make the claim of a deemed refusal and ask you to review it, or both?

Ms Falk

: There are the two options available. My view is that where, at the heart of the matter for

the individual, they are requesting access to documents, the matter is ordinarily better dealt with as an

Information Commissioner review of a deemed refusal of those documents. In many of those cases the

issues of process can be considered within the ambit of the Information Commissioner review. There

are some cases where that is not the case, where really the heart of the matter is a complaint around

service or a complaint around delay, in which case a complaint application is more appropriate. So it is

a little circumstantial, but my guidelines issued do say that where IC review is available that would be

the preferred course of action of my office.

Senator PATRICK: Thank you. I'll pass that on. As of 25 October 2019, according to an answer you

provided, there were 361 open Information Commissioner reviews that had been on hand for more

than 12 months. What's the figure as it stands today—how many reviews have been with you for more

than a year?

Ms Falk

: I might, if I may, make a couple of contextual remarks around that. You'd be aware that,

since 2015, the numbers of Information Commissioner review requests to my office have increased by

82 percent. During that same period of time, due to the best efforts of my staff and process

improvements, we've managed to increase our closure rates by 45 percent. But, unfortunately, the gap

between the work coming through the door and that which we can process is there. That does mean

that the time to resolve matters is more extended than would be certainly ideal. We currently have 991

IC, Information Commissioner, reviews on hand. Of those, 443 are more than 12 months old and 59

are more than two years old.

Senator PATRICK: So the situation isn't getting better. I know you'd had some consultants come in

and you were looking for efficiencies.

Ms Falk

: Senator, we have managed to—

Senator PATRICK: Where do you go from here? We know you're doing the work of three

commissioners. There are three commissioners named in the act—an FOI Commissioner, a Privacy

Commissioner and an Information Commissioner and—so please don't take this as a criticism of the

office. But, at an inquiry in relation to an FOI bill that I had before the Senate, the department

conceded there was a close-to-crisis situation. How do we resolve this?

Ms Falk

: Senator, you've mentioned that we have been successful in terms of process refinements

and we continue to do so. We have finalised last financial year more IC reviews than in the history of

the office, so we continue to increase our productivity. We also are working within the resources that

we have to look at issues that might be able to be of broader application throughout agencies that

would then impact the system more broadly. So, to give an example: I encourage agencies to look at

opportunities to give access to information administratively but also to look at opportunities for

proactively publishing information that's often requested by citizens. So, in that way, people don't have

to use the FOI Act to find the information. We're looking at those aspects to try and ensure the overall

FOIREQ20/00232 - 011

efficiency of the system for everyone. But you have raised the challenge that arises with a considerable

increase in the workload of the office and the issues that that raises.

Senator PATRICK: Have you looked at the number of reviews that you've done that lead to—in the

case management phase, you might reach a negotiated settlement or indeed when you finally make a

decision as to how many of those involved decisions where the department should have released the

information. That is: if there's a culture of restraint in terms of providing information under FOI, a

feeling of a tendency to release less than more, if across government that attitude was adjusted, would

mean there would be fewer reviews. Have you looked to see if the number of reviews results from an

increase in secrecy by departments?

Ms Falk

: There are a couple of remarks I can make in relation to that. The first is to reiterate the

pro-disclosure tenets of the FOI Act and my messaging to government agencies to take a proactive

approach where that's appropriate. But, if I look at the agency's statistics that have to be provided to

my office each year, that is really where I can see at least one indicator of the health of the system. If

we look at last financial year, the percentage of matters where documents were provided, either in full

or in part, is broadly consistent across the years from 2011-12. Thirteen per cent were refused last

financial year, and that compares to 12 per cent back when the office was established. Similarly,in

terms of the numbers where access was provided in full last financial year, it was at 52 per cent, and

that compared to 59 per cent back in 2011-12, and for those provided in part last year it was 35 per

cent, compared to 29 per cent.

You also raised the issue of my IC reviews and the extent to which—perhaps one way of looking at it

is the number of matters where I'm affirming agencies' decisions or varying those decisions. I'd say

that they're fairly even. A number of the decisions, however, that come to me have already been the

subject of negotiation with my case officers and departments, and that may have enabled the agency

to make a varied decision and release further documents. So it might be that the scope of what I'm

looking at is much narrower than that of the original decision-makers.

Senator PATRICK: I'm just thinking of that

Utopia clip on FOI. I'm sure you've seen it a few times?

Ms Falk

: What would make you think that I watch

Utopia, Senator?

Senator PATRICK: It's mandatory if you want to understand government. But anyway—

Senator PAYNE: It's a documentary, isn't it?

Senator PATRICK: That's correct. I refer to question on notice AE19-011 from 19 February 2019,

so about a year ago. You provided a range of statistics in relation to disposal rates and so forth. One of

the tables in there—I don't know if you have that question available, because I don't want to—

Ms Falk

: Would you provide the number again please.

Senator PATRICK: It is AE19-011 of additional estimates 2018-19. It was in relation to a question I

asked on 19 February 2019.

Ms Falk

: I don't have it in front of me, sorry.

Senator PATRICK: Okay. I'll read this out. There was a table that you provided that said:

This table provides the forecast future pending-to-disposal rate (PDR) at the end of each year. The PDR can

be used as a proxy for gauging future timeliness of matters to be disposed. For example, a PDR of 0.5 equates

to an approximate average finalisation time of six months.

You indicated for Information Commissioner reviews that for 2019-20 you expected 0.5 and for 2020-

21 you expected 0.5, getting to 0.4 in 2021-22 and 0.4 in 2022-23. Clearly, you're not hitting that,

unless I misunderstand what you were referring to.

Ms Falk

: That's a particular formula and I'd need to look at the data in relation to that particular

construct. The information that I have in front of me this evening is around the length of time for

allocation, average completion time of those that are finalised—around eight months—and that's

remained fairly consistent. We have had an 11 per cent decrease in IC reviews in the first six months

of this financial year. I would need to look at all of that.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 012

Senator PATRICK: Is that decisions made?

Ms Falk

: No, applications to my office.

Senator PATRICK: Applications?

Ms Falk

: Yes.

Senator PATRICK: So you had made a prediction for 2019-20 of 1,322 applications?

Ms Falk

: Yes.

Senator PATRICK: You've got fewer?

Ms Falk

: Currently on hand we've got around 991.

Senator PATRICK: You said that's what you've got on hand. That might be different to those that

apply—

Ms Falk

: Applications received were 461 for six months.

Senator PATRICK: Okay. So that's down quite a lot. That's a good thing.

Ms Falk

: It is 11 per cent.

Senator PATRICK: I will leave it at that. I might put the rest of my questions on notice.

Senator CHANDLER: What was the amount of the additional funding committed by the government

for the OAIC in the last budget?

Ms Falk

: It was $25.1 million over three years.

Senator CHANDLER: What was that specifically for?

Ms Falk

: It was specifically to provide a timely privacy complaint handling service, and also to

regulate and take action in relation to the privacy of Australians online.

Senator CHANDLER: Before I ask what good use you've been putting that $25.1 million over three

years to, what were the policy reasonings behind that? Obviously we know that privacy in this world,

where we all have mobile phones and computers, and the internet is readily available, is becoming a

greater concern. Could you perhaps explain what the drivers were behind that increase?

Ms Falk

: Yes. The work in terms of privacy to my office has continued to increase since 2015.

There's been a significant increase in the number of privacy complaints made to my office. We've also

established the Notifiable Data Breaches scheme. The government made legislation on that, which

commenced on 22 February 2018. As you've pointed out, aside from a heightened community

awareness of privacy issues, personal information is really what is driving the digital economy. It's also

a key input into service delivery by government. So both of those factors together, coupled with new

and perhaps unexpected uses of personal information, particularly online, I think, is some of the basis

for, certainly from my perspective, the need for my office to have additional funding and also, from a

regulatory perspective, to ensure that into the future we're able to have the capability within the

organisation to take the regulatory action that's required, from education and voluntary compliance

through to exercising some of the other powers that I have around taking action to the Federal Court

for civil penalties.

Senator CHANDLER: I foreshadowed this in my last question, but what further initiatives have you

been actioning that this $25.1 million is being spent on to target the issues you raised?

Ms Falk

: The first is that we've been able to increase our staffing capability. From 93 staff, we now

have an ASL cap of 124. We had a considerable backlog of privacy complaints. We had 300 matters

awaiting early resolution. We no longer have a backlog. We've also had considerable backlogs for

conciliation and investigation, and all of those matters are now being actively worked upon. We've also

been able to establish a determinations team that can then prepare decisions for my ultimate decision-

making around individual privacy complaints. At the same time, we've been increasing our capability

for my office to take action on my own initiative. We now have a considerable body of intelligence from

the Notifiable Data Breaches scheme, having operated now for two years, and there is an opportunity

to look at systemic issues in terms of data security and where enforcement action might be necessary,

FOIREQ20/00232 - 013

both in order to provide a remedy but also as a deterrent to ensure that entities are taking privacy of

personal information and security seriously.

Senator CHANDLER: What are some of the concerns you've had out of that data analysis across

your organisation?

Ms Falk

: I released a report a couple of weeks ago which was a six-monthly analysis of July to

December last year. That showed that predominantly the causes of data breaches are malicious and

criminal attack. Of those, the main reason personal information is being compromised is individuals are

being lured through phishing emails to provide their user name and password and that's enabling

malicious actors to enter systems. One of the big issues that we have seen in that six-monthly report is

the use of those credentials to access email systems and, within that, I've seen increased examples of

entities storing sensitive personal information within email systems. So that sensitive information really

should be stored in secure areas of organisations, not within email systems where it can be more

readily accessed if it be breached.

Senator CHANDLER: Wonderful. You mentioned 'conciliation' in your response just now. I'm really

interested to know—what does that look like in the privacy space and within the remit of your work?

Ms Falk

: I might turn to my colleague, Ms Hampton, who's been doing the change management

work in relation to the backlog strategy and the conciliation program.

Ms Hampton

: In the first instance, when there is a complaint made to the office, we have an early

resolution process whereby the parties are brought together and information is exchanged, and we

establish whether or not the office has jurisdiction and there is a prima facie breach of the privacy law.

Many cases resolve at that early stage, which generally takes place in the first month. But following

that, there is a requirement under the Privacy Act that unless a matter is unable to be conciliated that

a conciliation should be attempted as a method of resolving the matter prior to proceeding to

investigation and determination, so it's an important and a statutory step in the process of resolving

privacy complaints to the office.

Senator CHANDLER: Great. I don't think there's anything more I have on funding. Thank you very

much.

Senator CHISHOLM: You might recall that at last estimates I asked some questions about the

culture of secrecy within the Department of Home Affairs and its failure to comply with the Freedom of

Information Act. I noticed that, following Senate estimates, you announced an investigation into Home

Affairs compliance for the Freedom of Information Act. Is that correct?

Ms Falk

: Yes, I did. That matter had been under consideration for quite some time. We had been

analysing the statistics that agencies submit to my office at the end of the financial year and also

monitoring the Information Commissioner review applications that were being received by my office

relating to the Department of Home Affairs. So there were a number of factors that together led me to

the conclusion that it would be a worthwhile use of public resources to investigate the matter and then

to work with the Department of Home Affairs to improve their compliance.

Senator CHISHOLM: I wasn't seeking to take credit, for the record. How is the investigation going?

Ms Falk

: It's continuing. The department's cooperating with the investigation. We've requested

information that's been provided. There will be further requests for information being sought

imminently, so the matter is under active consideration.

Senator CHISHOLM: How would you describe the Department of Home Affairs co-operation with

your investigation? Have they responded promptly to your requests?

Ms Falk

: Yes, they have.

Senator CHISHOLM: When would you be expect it to be completed?

Ms Falk

: That's always the question, isn't it? It will in part depend on what we receive, in terms of

the information requests that we make. And then one always has to make an analysis of whether that

is sufficient or whether further information is required. I would think that it would be in the coming

months and certainly by the end of this financial year.

CHAIR: We appreciate your evidence today. Thank you very much for your patience in the course of

the day. We will see you next time estimates is on.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 014

Ms Falk

: Thank you, Chair.

CHAIR: The next agency we have on our list is the High Court of Australia.

Tuesday 22 October 2019 (Estimates): Senator HENDERSON: Commissioner, I'd like to ask you about the funding for the Office of the Australian

Information Commissioner; in particular, the amount of additional funding committed by the government

for the office in the last budget.

Ms Falk: In terms of the operating budget of the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, the

total revenue for this financial year is $23.234 million. That includes appropriation of $20.941 million and a

sum which comes to the office through memorandums of understanding of around $2.3 mil ion. In terms of

the second part of your question, around the additional funding provided to the office, the 2019-20 budget

allocated $25.121 million over three years to undertake functions around the handling of personal

information and taking enforcement action. The purpose of the funding is to ensure timely handling of

privacy complaints, also particularly focused on regulating the online environment. It is envisaged that my

office would create a regulatory code that would apply to online providers such as social media companies,

and it would set out particular protections in terms of vulnerable Australians, including children…

…other text deleted…

…So one of the big shifts in my office at present is shifting from an organisation that has predominantly

been, in terms of privacy, an alternative dispute resolution body focused on conciliation, with

administrative decisions being made in only some cases. It's clear that the community expectation of

regulators—also the government has announced its intention to increase penalties under the Privacy Act

and the enforcement mechanisms available to me—that a strong enforcement approach is required. That

means increasing our capability. We are increasing the ASL, up to 124 staff, this financial year. We are

currently at around 90 and we will be looking particularly at increasing our capability to act in that

enforcement role.

Senator KIM CARR: Did I hear you correctly in your opening statement? Did you actual y say that you're

under-funded?

Ms Falk: I did raise the issue of resourcing in terms of FOI. It's a matter that's been discussed before this

committee on a number of occasions, where I've indicated that real y where the stresses in the system lie,

from the OAIC's perspective, are with the need for more staffing. I've set out the fact that we've had an 80

per cent increase in Information Commissioner reviews and I have worked very purposefully since being in

the role on looking at how we can increase our efficiency. Over that same period of time—the four-year

period—we have increased our efficiency by 45 per cent. But I've formed the view, having conducted a

number of reviews of the way in which we're carrying out our work, that the only way in which the gap is

to be bridged is for additional staffing resources to be provided.

Senator KIM CARR: I see. I was just trying to reconcile the line of questioning from Senator Henderson with

your statement, that's al . When was the first time you requested additional funding?

Ms Falk: I'd need to take that on notice.

Senator KIM CARR: Are you sure you need to? Most officers in your position would be able to tel very

quickly when they first sought additional resources, given the growth in the workload.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 015

CHAIR: The question's asked and answered. She's taken it on notice.

Senator KIM CARR: I'm just surprised that you need to take that on notice. Because what—

Ms Falk: It's been a matter of discussion with this committee and also, of course, with government during

my term. I'm just unable to recall, with accuracy, the first occasion on which that occurred.

Senator KIM CARR: I see what you mean. I do apologise. In my experience, officers in your position are able

to identify at least the year in which they asked for additional resources.

Ms Falk: I have asked for additional resources since being appointed to the position in August last year but,

in terms of the first occasion subsequent to that date, I would need to check.

Senator KIM CARR: I see. That's where the confusion lies. So, since August last year, you've been seeking

additional support?

Ms Falk: Sometime after that date, Senator.

Senator KIM CARR: And what was the government's response?

Ms Falk: The government has acknowledged my request and is working through it in terms of normal

budget processes. (QoN)

Senator KIM CARR: I appreciate that agencies will ask for additional resources and it won't necessarily be

the same amount as the ERC thinks you're entitled to, but what is, in your assessment, the requirement?

How much do you need to do your job in terms of the report that you've given to us today about the

additional demand on your agency?

Ms Falk: The amount of additional resources depends on the objective which is sought to be achieved. Of

course, the more staffing resources that you have for processing Information Commissioner reviews and

complaints, the quicker they can be processed.

Senator KIM CARR: So you don't have a figure?

Ms Falk: I think that there needs to be an increase in the staffing resources, and the quantum of that does

depend on the time in which the backlog is sought to be addressed and also the ultimate goal in terms of

how quickly Information Commissioner reviews should be handled.

Senator KIM CARR: So how much did you ask for?

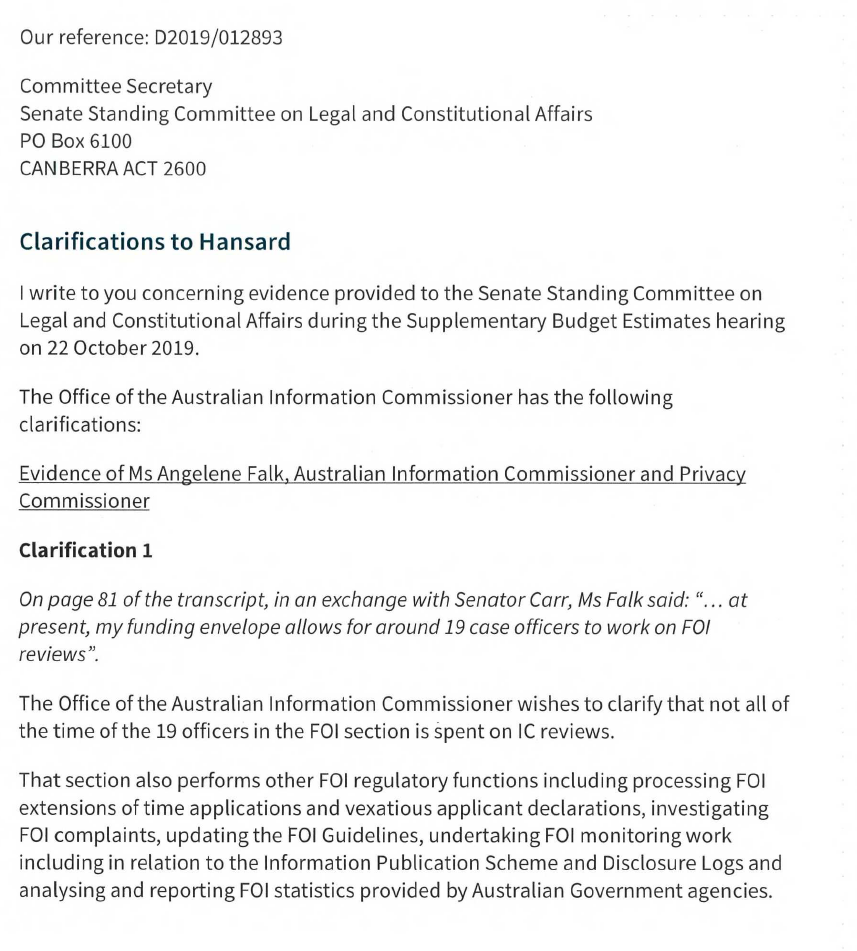

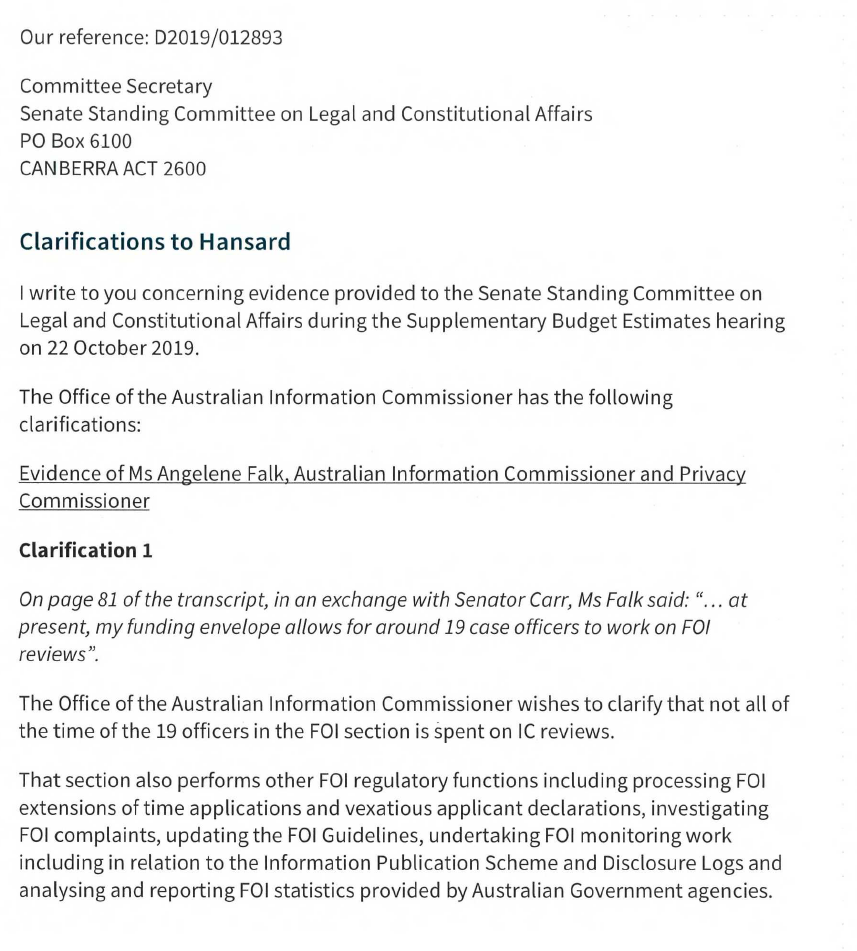

Ms Falk: Senator, you appreciate that the information I've provided to government is through budget

processes. I can give you an indication that, at present, my funding envelope al ows for around 19 case

officers to work on FOI reviews—there are additional staff who work on the FOI function more broadly—

but just looking at FOI reviews, there'd need to be at least a half increase in the number of those staff.

Senator KIM CARR: What you mean by 'a half'?

Ms Falk: A half again.

Senator KIM CARR: So—

Ms Falk: Another nine staff.

Senator KIM CARR: What will that cost in terms of your normal profile?

Ms Falk: I'd need to see if we've got any figures to hand in relation to that, but it would be the cost of those

staff.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 016

Senator KIM CARR: It depends on what they're paid, doesn't it? Those nine staff are not all SES staff, are

they?

Ms Falk: No, they're case officers.

Senator KIM CARR: So you'd be able to indicate roughly what it would cost to fund nine staff.

Ms Falk: I've put forward to government the cost of that and also any capital costs that might be needed to

accommodate those staff.

Senator KIM CARR: Can you take that on notice, please? (QoN)

Ms Falk: Thank you.

Response to QoN:

The response to the honourable senator’s question is as follows:

The OAIC provided a submission to government in relation to additional resourcing, including for its FOI

functions, in November 2018. An updated submission in relation to the OAIC’s FOI function was provided to

government in September 2019.

Response to QoN:

The response to the honourable senator’s question is as fol ows:

FOIREQ20/00232 - 017

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner has estimated that the annual cost to fund nine (9)

additional staff to undertake FOI regulatory work, including processing IC review applications, would be

approximately A$1.65 mil ion with an additional capital amount of approximately A$0.3 mil ion for

accommodation in the first year.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 018

Tuesday 9 April 2019 (Estimates): reference to ASL

Senator PATRICK: Good morning, Ms Falk. I have a few lines of questioning. Firstly, in relation to the

budget, it looks like you have a relatively significant increase in funding. Could you talk me through that

funding and how you intend to use it?

Ms Falk: Since the last occasion that I appeared before the committee the government has announced a

proposed provisions to strengthen privacy protections under the Privacy Act, including increased penalties

and a new system of infringement notices. Importantly, my office will receive $25 million over three years

to deliver new work, as well as to enhance the office's ability to prevent, detect, deter and remedy

interferences with privacy. It is also intended that there wil be an enforceable code to introduce additional

safeguards across social media and online platforms that trade in personal information. The code will

require greater transparency about data-sharing and requirements for the consent, col ection, use and

disclosure of personal information. This will incorporate stronger protections for children and other

vulnerable Australians within the online environment. Accordingly, the OAIC wil be focused on working

col aboratively and constructively with al parties to enhance privacy protections both online and offline

and to give Australians greater control over their personal information, ensuring that it is handled in a way

that is transparent, secure and accountable.

Senator PATRICK: Does that new function have new employees attached to it?

Ms Falk: It does. At present we have an ASL cap of 93 staff, and that wil be increased to 124. That takes

account of this new measure. It also includes some additional staff for the consumer data right, a measure

which was introduced in the last budget.

Senator PATRICK: Do I also detect an increase in capital expenditure?

Ms Falk: There is an increase of $2 million for capital. At present the OAIC requires additional

accommodation, particularly with this new investment and increased staffing.

Senator PATRICK: You operate out of Sydney?

Ms Falk: That's right.

Senator PATRICK: Is that a lease of a building or something?

Ms Falk: It will be. We are making inquiries in relation to that at this time.

Senator PATRICK: We didn't real y get much in the way of increased funding for FOI, I presume, based on

that previous statement?

Ms Falk: There was no specific funding for FOI.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 019

Tuesday 19 February 2019 (Estimates): reference to NDB

Senator PRATT: Journalists have been refused access to documents and are therefore raising concerns

about the delays and the time it takes to have a government refusal of a decision reviewed by the Office of

the Australian Information Commissioner. A key concern given to us is that, by the time a review is

completed, the subject matter of the news story may no longer be current. This means that the

government of the day may refuse an application entirely on spurious grounds, knowing that, even if the

decision is ultimately overturned, the delay caused wil ensure the information does not reach the

Australian public in a timely and meaningful way. Would additional resources assist you in dealing with

applications for the review of FOI decisions in a more timely manner?

Ms Falk: It's my responsibility to prioritise the appropriation that has been given to the office. I've talked

through some of the strategies that we've put in place, including early resolution. We've tripled the

number of matters for IC reviews that have been varied by agreement. There are early resolution processes

that result in changed decisions, that result in further documents being provided to applicants. So we are

seeing results. The figures that I've given you are a number of matters which are more complex in nature

and have further exemption applications that may be applied to them.

…

Senator PATRICK: We'l go back once again to the burden of Senator Pratt's question. I'l just read the

testimony of Mr Walter from the Attorney-General's Department. At a recent hearing he conceded, 'There

are undoubtedly stresses in the system.' You're conceding that there are stresses in the system inherently

by the fact that you have al these delays running through the system. I say this in the context that ASIC

used to say: 'No, we've got enough resources. No, we've got enough resources.' When the whole system

breaks the reality pops out. I cannot understand how you could be sitting in your position as a statutory

officer with obligations, knowing that there are stresses and knowing that you're fal ing behind—

notwithstanding that you are working as efficiently as you possibly can with the resources you have—and

not be able to form the view that you require additional resources.

Ms Falk: I've not said today that I don't require additional resources—in fact, the contrary. I was asked a

question earlier around the three-commissioner model and my answer went to the fact that I thought that

that was working well at this time—if that were to change, I would advise government—but what is

required is additional resources at the staffing level. I understand that that may not have been clear at the

time. But I have been on record a number of times in terms of the increased workload and the fact that the

ability of the office to keep up with that workload is being chal enged. However, I don't think it's acceptable

as a statutory officeholder to simply say that the office requires more resources with nothing else added to

that. I think that would be simplistic.

It's incumbent on me to look at prioritisation across the office but also to understand the causes of the

increased work, to work in terms of the proactive educative strategies that I've outlined and to ensure that

we are taking a holistic approach to looking at our processes and that we are doing the best that we can.

We can see over the last few years that we have continued to increase our throughput, and that's through

trialling different pilots and different methodologies and looking very critically at our processes. I will

continue to do that. There would be no regulator in the country, I'm sure, who wouldn't say that,

inevitably, time frames couldn't be improved with additional resources, and I'm no exception to that.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 020

Monday 22 October 2018 (Estimates): reference to NDB

Senator MOLAN: You spoke about finalising most data breaches—99 per cent within 60 days—but it may

have deteriorated. Which of those figures deteriorated? Are you dropping the percentage? Or are you

doing things faster? I was just a bit unsure.

Ms Falk: I've now got a note in front of me. In the first period of reporting, from when the scheme started

on 22 February this year to 30 June, we resolved those data breach notifications in 60 days 99 per cent of

the time.

Senator MOLAN: Good.

Ms Falk: We're now resolving those matters within 60 days 87 per cent of the time.

Senator MOLAN: Okay. That's not bad. And that's of the 305 that you've counted between the periods you

mentioned?

Ms Falk: That's correct.

Senator MOLAN: How many staff are al ocated to that function?

Ms Falk: There are a little over nine staff that are allocated at the moment, but they carry out a variety of

roles.

Senator MOLAN: Out of how many total in the organisation?

Ms Falk: At present the total number in the organisation is 88 full-time equivalent.

Monday 22 October (Estimates): reference to FOI and other areas

Senator PRATT: Thank you. If you could take on notice the statistics for each quarter over the last couple of

years, that would be great. Clearly the workload is increasing. How many staff do you have handling FOI

matters?

Ms Falk: In relation to FOI at present—and it's always a point-in-time snapshot—we have around 22 full-

time-equivalent staff.

Senator PRATT: Have you increased the number of staff handling FOI matters from the point last year

where you had 168 to the point now where you have 281 matters?

Ms Falk: Yes, we have. There was a return of some funding from the AAT and, as a result of the return of

that funding, we've increased the FOI staff. In August of this year, we implemented a new structure in our

FOI area to give greater capacity.

Senator PRATT: You've currently got 22 staff.

Ms Falk: Yes.

Senator PRATT: What was it at the time when you had 168 matters?

Ms Falk: I would have to take that on notice. (QoN)

Senator PRATT: Okay, thank you. How does that compare to the number of staff you have handling other

matters, and what is the time taken on average? Has the time to resolve FOI matters increased as the

workload has increased?

Ms Falk: In terms of other matters, we have around seven staff that work across the office on our

governance and support, and then we have around 61 people who work on privacy matters. We received

some additional funding in this budget for the proposed consumer data right, which we have responsibility

for implementing with the ACCC, and that provided an extra 10 FTE. I also mentioned earlier that there

were some specific MOUs in relation to privacy.

Senator PRATT: Thank you.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 021

Response to QoN:

The response to the honourable senator’s question is as fol ows:

The 22 staff represent the contribution to delivering FOI functions from across the Office of the Australian

Information Commissioner.

Fol owing the reallocation of FOI funding from the Administrative Appeals Tribunal the Office of the

Australian Information Commissioner assigned an additional three staff to handle FOI matters.

Friday 16 November 2018 (FOI hearing): reference to FOI and general resources

Senator PRATT: So, in that sense, you are identifying these problems? Are you trying to paper over the

nature of that problem because it is a political decision that there is only one commissioner at this point in

time?

CHAIR: That's not a very fair question to the commissioner.

Ms Falk: I'm happy to answer it, because the answer is no. I'm giving my considered view, having worked

both in the office for over 10 years and then as the appointed commissioner, as to where I see the

chal enges in the process and where I think we can best address those issues. Should that situation change,

then that's something, of course, that I would continue to monitor. But, at present, the one-commissioner

model is not the subject or the cause of some of the issues that I think have been brought to bear by

evidence today; it's an overall resourcing issue. Having said that, I want to acknowledge the incredible work

of my staff in terms of dealing with an increased workload, working to look for more efficiencies and

always working in the public interest. I'd like to put that on record.

Senator PRATT: If you, as commissioner, did have more resources and, therefore, there were a speedier

triage, could that not accelerate the number of cases that you're ultimately responsible for making a

decision on?

Ms Falk: Alternatively, it could resolve more that no longer require a decision, because that would mean

that we're engaging with higher numbers of parties more quickly when there perhaps is more of a

willingness to reach an agreement in relation to the matter.

Thursday 24 May 2018 (Estimates): Commissioner Falk – opening statement

Turning briefly to some of the other priorities for the OAIC, we're focused on implementing the new

notifiable data breaches scheme, which is in its early stages. We're also preparing the OAIC and

government agencies for the commencement of the Australian Government Agencies Privacy Code on 1

July, including providing detailed guidance and resources. The committee may also be aware that the OAIC

has received additional funding of $12.9 mil ion over the forward estimates to support strong privacy

protections under the government's proposed consumer data right.

Thursday 24 May 2018 (Estimates): financials and staffing

Senator PRATT: That makes sense. So it's not therefore a lack of—I was going to say that therefore al

senior roles in the commission are not permanent, but there's some permanency there because Ms Falk

has been the deputy commissioner. Ms Falk, I'd like to ask you some questions about funding. You were

allocated $16.1 million for the next financial year—no, that doesn't sound right. Can you tel us what your

al ocation is for the most recent budget?

Ms Falk: Under the current budget for 2017-18, the appropriation is $10.74 million. There's an additional

amount that the OAIC receives from government agencies to MOU funding of $3.021 mil ion. Then, in

FOIREQ20/00232 - 022

2018-19, we will receive $13.496 million. That includes an additional $2.779 million, which I mentioned in

my opening statement, for the proposed consumer data right.

Senator PRATT: As far as I can see, there's a cut over the period of the forward estimates in what you were

allocated for the next financial year versus what falls over the forward estimates.

Ms Falk: At 30 June 2019, there wil be a measure that terminates. That's the enhanced welfare payment

integrity non-employment income data-matching measure. That will terminate, as I said, on 30 June 2019.

Senator PRATT: What was the al ocation attached to that?

Ms Falk: It is approximately $1.3 million.

Senator PRATT: What's the total decline over the forward estimates relative to your income for this next

financial year?

Ms Falk: There are no other significant decreases in terms of terminating measures. The only other

decreases relate to efficiency and other measures that occur throughout the portfolio, and they're

allocated to the OAIC accordingly.

Senator PRATT: Okay. I'm trying to see if I've got an attachment that shows this. Can I ask about whether

you've had to cut any staff to absorb funding cuts?

Ms Falk: We have not had to cut staff in this financial year.

Senator PRATT: Looking forward, do you expect that your staffing allocation will remain the same?

Ms Falk: Our staffing allocation will increase next financial year. We'll move from having an ASL of 75 to

having an increased ASL of 92. That takes account of the new budget measure on the consumer data right.

We are in a fortunate position of actually being able to go out to recruit, and we're, at the moment, making

arrangements in order to move that forward.

Senator PRATT: Okay. You look like you're having an ASL increase, despite what looks like a decline over

the forward estimates. How are you funding that?

Ms Falk: As I mentioned, there is the additional appropriation for the consumer data right. What the

forward estimates don't specify is the amount that we're likely to get under the memorandum of

understanding. The only memorandum of understanding remuneration that's mentioned there relates to

two MOUs that we know are on foot now and wil continue next financial year, and that's $2.07 mil ion for

the digital health system and an MOU we have to regulate the unique student identifier, for $100,000. We

have a number of other MOUs that are terminating at 30 June, and we're in negotiations to renew those.

As I said, they currently amount to over $3 mil ion for this financial year, and we would expect funding in

relation to a commensurate amount to continue over the forward estimates.

Senator PRATT: If you could you tel us on notice which programs that aren't covered in your base

al ocation you've got over the forward estimates, which ones are finishing and which ones you're working

on having renewed, that would be—

Ms Falk: Thank you. We will.

Senator PRATT: And the value of the budget attributed to each of those. (QoN)

Ms Falk: Thank you, Senator.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 023

Thursday 24 May 2018 (Estimates): Staffing/NDB

Senator STEELE-JOHN: Just finally—and I'm all done—how many staff have you al ocated to handle these

notifications and have you received additional funding to support the NDB Scheme?

Ms Falk: We've not received additional funding. In relation to staff handling the matters, we have around

five staff at present who are handling notifiable data breaches and also our proactive commissioner-

initiated investigations. They would also have a privacy complaint caseload as well.

Thursday 24 May 2018 (Estimates): Staffing/FOI

Senator PATRICK: Ms Falk, with respect to the question that Senator Steele-John was asking, how many

overall staff do you have at the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner?

Ms Falk: We have 75 FTE at present.

Senator PATRICK: Split between privacy and FOI?

Ms Falk: Yes, that's right.

Senator PATRICK: Is there a mud map in your annual report, as to the positions and what functions people

perform?

Ms Falk: There is information in the annual report in terms of the way in which the organisation is

structured into two branches. We have our dispute resolution branch that deals with both privacy and

dispute resolution, and also Information Commissioner reviews and complaints. Then we have a regulation

strategy branch, which is around our guidance, advice, monitoring and also conducting assessments.

Senator PATRICK: When you said that five people have been transferred or are now looking at the NDB

complaints, what were those people previously doing?

Ms Falk: They've not been transferred. They're people who were dealing with the voluntary data breaches

in the scheme that we ran before the mandatory scheme. They also deal with commissioner initiated

investigations and inquiries, and they would also have a privacy caseload.

Senator PATRICK: How does that gel in terms of workload, now that they've got a new function?

Ms Falk: There has been an increase in that workload. We have had to put in place different systems and

processes, and use our IT environment in new ways to try and create some efficiencies there. There's

definitely a workload increase across the office. I'm very grateful to the staff for the very flexible approach

that they're taking to manage the work. There's a commitment to look at what our ongoing needs are

going to be into the future, and I've certainly been in discussion with the department in relation to that.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 024

Response to QoN:

The table below contains Memorandum of Understandings that provide funding in addition to

departmental appropriation:

Description

Type of funding

End date

Amount

Status as at

26 June 2018

Australian Bureau of Memorandum of 30 March 2018 $175,000 for Finalised MOU

Statistics: Provision

Understanding

2017-18

of Privacy Advice

Department of

Memorandum of 30 March 2018 $75,000 for

Finalised MOU

Home Affairs: Visa

Understanding

2017-18

Reform Program

ACT Government:

Memorandum of 30 June 2018

$177,146 for Renewal

Provision of Privacy Understanding

2017-18

anticipated

Services

Department of

Memorandum of 30 June 2018

$65,000 for

Renewal

Immigration and

Understanding

2017-18

anticipated

Border Protection:

Passenger Name

Record data

Department of

Memorandum of 30 June 2018

$220,000 for Renewal

Human Services:

Understanding

2017-18

anticipated

Priority Privacy

Advice

Australian Digital

Memorandum of 30 June 2019

$2,070,000

Current MOU

Health Agency: My

Understanding

for 2018-19

Health Records Act

2010 and Healthcare

Identifiers Act 2012

Department of

Memorandum of 30 June 2019

$100,000 for Current MOU

Education and

Understanding

2018-19

Training: Student

Identifiers Act 2014

Attorney-General's

Memorandum of 30 June 2019

$75,000 for

Current MOU

Department:

Understanding

2018-19

National Facial

Biometric Matching

Capability

FOIREQ20/00232 - 026

Attachment D: COVID-19 & OAIC Funding Article – Innovation Australia

D2020/010421

FOIREQ20/00232 - 027

FOIREQ20/00232 - 028

Commissioner brief: Complaint backlog strategy

Key messages

• In 2019, the OAIC was provided with an additional $25.1 mil ion over 3 years (including

capital funding of $2.0 mil ion) to facilitate timely responses to privacy complaints and

support strengthened enforcement action in relation to social media and other online

platforms that breach privacy regulations. The OAIC used part of this funding to reduce

the backlog of privacy complaints.

• The OAIC took a multi-pronged approach, focusing on the processes around new

incoming complaints, the older complaints awaiting investigation, conciliation, and the

matters requiring determination by the Commissioner.

• Due to these efficiencies—and with the support of additional funding—the OAIC closed

3,366 privacy complaints during the 2019-20 financial year–a 15% improvement on

2018–19.

Critical facts

• Over the last few years, until the Covid-19 pandemic, the OAIC has experienced a

steady increase in the number of complaints received. This, coupled with static

resourcing and staffing levels, resulted in an increase and backlog of complaints

waiting to be al ocated to case officers: for early resolution, and if not resolved, for

investigation.

• The relevant Directors and Team Managers reviewed statistics and team processes to

consider any efficiencies that might be achieved both within each team, and to the

overal complaint process.

• Contractors were engaged to increase the number of staff in each complaint team, and

to establish a new determinations team.

• The Directors of the two complaint teams (Early Resolution and Investigation &

Conciliations) and the new Determinations team worked closely together to develop

new strategies and processes to streamline the complaint process. These included:

o reviewing our complaint management system to identify any changes that would

assist staff in processing matters more swiftly

o establishing new queues in our complaint management system, to further

differentiate types of matters

o updating template letters to ensure key messages were communicated to parties

o introducing tighter timeframes in the complaint handling process to streamline

matters through early resolution

o establishing tight timeframes for completion of an investigation where early

resolution was not successful

FOIREQ20/00232 - 029

o substantial y increasing the number of conciliations conducted to seek to reach

resolution by agreement

o providing additional resources to assist with the determination of matters where

appropriate.

• The project started on 4 November 2019, with the first phase completing at end

January 2020 and the second in mid-May 2020.

• At the end of June 2019, we had 1465 complaints on hand with 316 awaiting allocation

and had closed 727 matters (compared with 690 closed the previous year) with an

average handling time of 5.4 months.

• After completion of the project by end June 2020, we had 785 matters on hand with 79

awaiting allocation and had closed 554 matters with an average handling time of 5

months.

• Although the numbers of complaints received in financial year 2019-20 had decreased

by 19% compared with the previous financial year, the number of matters closed

increased by 15%, being 3366 compared with 2920.

• For Quarter 1 2020-21 July- September 2020, we received 691 complaints and closed

515. Our average handling time for complaints in the financial year Q1 is 4.4 months.

• Matters are now listed for a conciliation within 14 – 21 days of receipt from the early

resolution team, with few exceptions.

Information about the Early Resolutions Team’s project

• The Early Resolution (ER) team ran a 3-month backlog project from 1 November 2019

to 31 January 2020.

• The ER Team reviewed its current work in progress and set aside any complaint

received between 17 July 2019 and 25 October 2019 and placed those 324 matters in a

‘backlog’ queue.

• The ER Team engaged 3 FTE contractors to replace three officers in the Privacy ER

Team, as those officers formed the ER Backlog Team. The total cost of these 3

contractors was $114,101.63 (inc gst).

• The team took a strategic approach to the problem which included having a smal team

in a separate space focused only on the backlog, batching complaints and

administrative improvements that made issues easier to identify. They also improved

templates, tightened timeframes and streamlined processes.

• At the end of the project: the team had closed 226 matters; 33 matters were referred

to the Investigations/CI team and the remaining 64 matters were finalised in following

weeks.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 030

DR Investigation & Conciliations team’s results

• The Investigation & Conciliations team ran its project from 4 November 2019 to 18

May 2020.

• The team reviewed and amended its processes, had staff trained as accredited

mediators and appointed FTE contractors to fil vacant positions.

• In the first phase the team focussed on reviewing older more complex matters,

preparing matters for investigation with conciliation at week 6, and finalising matters

against new time frames.

• By early February 2020, al matters in the investigation intake queue had been assessed

and moved to either a conciliations or an investigations queue.

• In the second phase, the team moved to a ful conciliation model, with conciliation

attempted prior to opening an investigation. At the time approximately 70% of

conciliations led to a resolution.

• Three FTE officers were dedicated to conciliating matters, a part time officer was re-

deployed as a conciliation listing clerk and two external conciliators were engaged. On

1 July 2019, the total backlog for the team was 639 matters of which 367 matters were

awaiting allocation. By 18 May 2020, the total backlog for the team was 200 matters

with 86 matters awaiting al ocation, 67 listed for conciliation and 47 under

investigation.

• At the end of the 2019-20 financial year, the team had 195 active matters with 74

awaiting allocation, 56 in conciliation and 65 under investigation.

• By end September 2020, the team had 172 matters with 77 awaiting al ocation, 38 in

conciliation and 57 under investigation.

Information about the Determinations Team’s approach

• The Determinations Team (DT) is comprised of one EL2 FTE, one APS 6 FTE and one

APS5 FT contractor. It commenced on 4 November 2019.

• DT has received complex complaints which have not resolved over a lengthy

conciliation and investigation period.

• DT drafts preliminary views (PVs) which are the precursor to a determination under s

52 of the Privacy Act, setting out a view on whether there has been a privacy breach

and recommended declarations. On receipt of a PV, the parties may decide to settle

the matter or provide submissions to the OAIC. On receipt of submissions from the

parties, DT assists the Commissioner by preparing the matter for determination.

• DT also uses powers under s 44 of the Privacy Act to complete investigations as

required and provides advice to investigations officers about evidence gathering.

• The DT has established new processes and templates to support this function.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 031

• DT has drafted 23 PVs and has finalised 8 determinations. To date, no parties have

successful y settled their matters after receipt of a PV.

Possible questions

•

Was the backlog project successful?

During the first 3 months of the backlog project (4 November 2019 – 31 Jan 2020) the

OAIC closed 905 complaints. Compared to the same period the last year (609

complaints) this was an increase of 296 complaints, or a 48% increase.

We have also seen further increases in the numbers of complaints finalised. In the

2017-18 financial year, the average number of complaints closed per month was 230.5,

which increased to 243.5 in the 2018-19 financial year. For the 2019–20 financial year,

the average was 280.5 complaints closed per month.

Since end January 2020, with changes in procedures we are also seeing earlier

resolution of matters al ocated to conciliation and investigation.

•

How did the average time taken to close a complaint improve during the backlog

project?

For the backlog project period 4 November 2019 to 31 January 2020, the average time

taken to close a complaint was 132 days, or 4.3 months. This was a significant

improvement from the start of the 2018-2019 financial year, as from 1 July 2019 to 3

November 2019 the average time taken to close a complaint was 5.1 months.

For the financial year 2019–20 overal , the average time taken to close a complaint was

also 5.1 months and by end of September 2020 it was 4.4 months.

•

Have waiting times for allocation improved?

The waiting times for al ocation improved in the Early Resolution space following the

backlog project. Before the backlog project the oldest matter awaiting al ocation was

just over 4 months old, and fol owing the ER backlog project (and first three months of

the Investigation backlog project) the oldest matter awaiting al ocation was just over 1

month old (as at 6 February 2020).

In the Investigation & Conciliations team, al matters awaiting al ocation to

investigation have either been to conciliation and not resolved or assessed as not

suitable for conciliation.

Conciliation are now listed for a conciliation within 14 – 21 days of receipt from the

early resolution team, with few exceptions.

How much was spent on external conciliators?

External conciliators were appointed to end June 2020, and the cost of these

conciliations was $26,666.49.

FOIREQ20/00232 - 032

Key dates

• Backlog project commenced on 4 November 2019

• The Early Resolution team’s project finalised in 31 January 2020 (phase one)

• The Investigation & Conciliations team’s project finalised in mid May 2020 (phase two)

• From 1 February 2020, the Investigation & Conciliation team began working on the

conciliation focussed model that is now in place.

Document history

Updated by

Reason

Approved by

Date

Cecilia Rice /Sara

October 2020 Senate Angelene Falk

October 2020

Peel/Cate Cloudsdale.

Estimates

FOIREQ20/00232 - 033

Commissioner brief: My Health Record

Key messages

• After the end of the opt-out period on 31 January 2019, the Australian Digital Health

Agency (ADHA) created My Health Records for al individuals. The records are available

to individuals and participating healthcare providers.

• During 2019-20, the OAIC’s regulatory work relating to MHR has focussed on:

o regulatory oversight of the privacy aspects of the My Health Record system,

including

o responding to enquiries and complaints,

o handling data breach notifications,

o providing privacy advice and

o conducting privacy assessments;

o engaging with the ADHA about the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO)

performance audit of the My Health Record system and the ADHA’s implementation

of the ANAO’s recommendations, as well as privacy aspects of the system more

general y;

o promoting guidance materials, including the Guide to health privacy, a privacy

action plan for health practices, and a new data breach action plan for health service

providers;

o promoting consumer resources including information about privacy and the My

Health Record system;

o providing preliminary input and preparing a formal submission to the Review of the

My Health Record Act 2012 (MHR Act), which is due to finalised by 1 December

2020.

• On 26 June 2020, the OAIC and ADHA signed an updated MOU, effective from 1 July

2020 until 30 June 2021, to provide $2,070,000 for its regulatory functions relating to

the MHR system under the