PROTECTED

DFAT Thematic Report

Conditions in Kabul

3 October 2014

PROTECTED

Contents

Contents

2

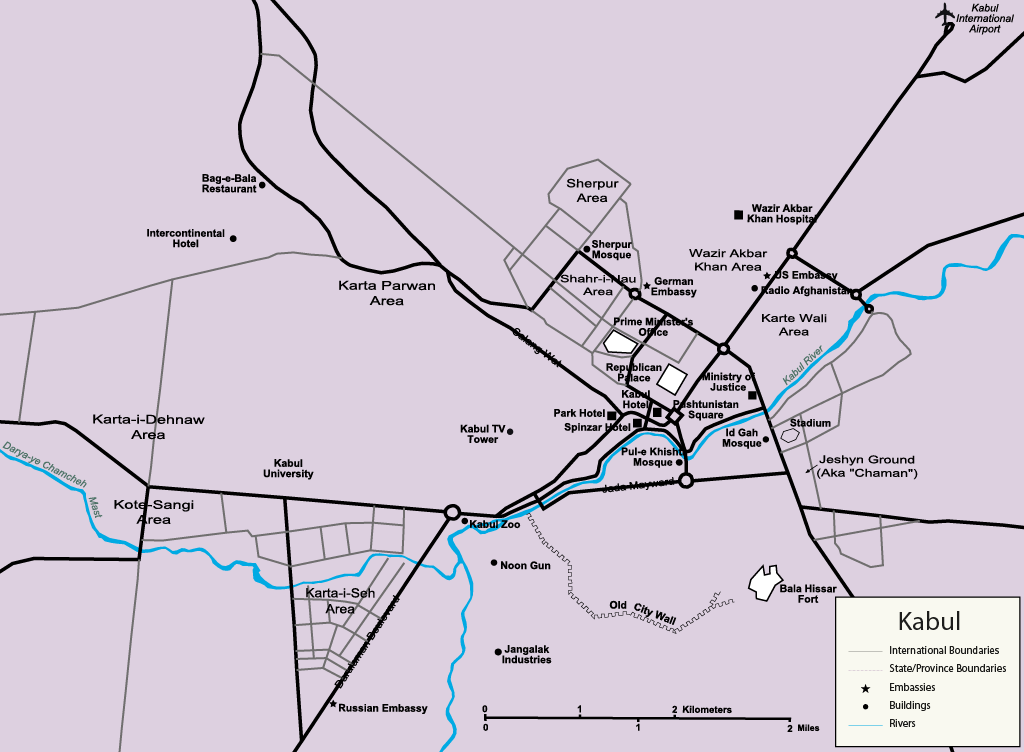

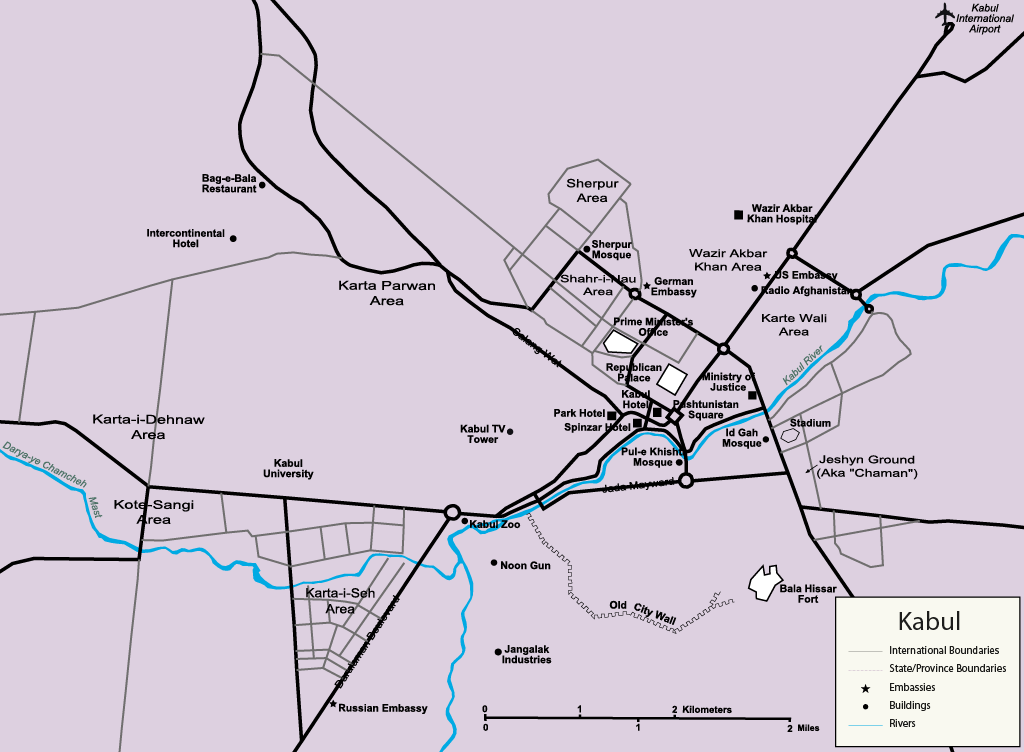

Map

3

1. Purpose and Scope

4

2. Background Information

5

Recent History

5

Economic Overview

5

Security Situation

7

3. Other Considerations

9

State Protection

9

Internal Relocation

9

Treatment of Returnees

10

2

DFAT Thematic Report - Conditions in Kabul

Map

DFAT Thematic Report - Conditions in Kabul

3

1. Purpose and Scope

1.1

This Thematic Report has been prepared by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) for

protection status determination purposes only. It provides DFAT’s best judgment and assessment at time of

writing and is distinct from Australian Government policy with respect to Afghanistan.

1.2

The report provides a general, rather than an exhaustive country overview. It has been prepared with

regard to the current caseload for decision makers in Australia without reference to individual applications

for protection visas. The report does not contain policy guidance for decision makers.

1.3

Ministerial Direction Number 56 of 21 June 2013 under s 499 of the

Migration Act 1958 states that:

Where the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has prepared a country information assessment

expressly for protection status determination processes, and that assessment is available to the

decision maker, the decision maker must take into account that assessment, where relevant, in

making their decision. The decision maker is not precluded from considering other relevant

information about the country.

1.4

This report is based on DFAT’s on-the-ground knowledge and discussions with a range of sources. It

takes into account relevant and credible open source reports. Where DFAT does not refer to a specific source

of a report or allegation, this may be to protect the source.

1.5

Information on the situation in Afghanistan more broadly can be found in the March 2014 DFAT

Afghanistan Country Report.

4

DFAT Thematic Report - Conditions in Kabul

2. Background Information

2.1

Kabul is bisected into east and west by a range of hills running from Afshar and Sorkh Kotal in the

north; by the Koh-e Asmayee and Koh-e Shir Darwaza in the east; by the Qorugh Mountain in the south; and

in the west by Koh-e Childukhtaran and its surrounding slopes. The Kabul River runs west to east through

the city.

2.2

Data on the population of Kabul is unreliable, including information on the city’s ethnic composition.

However, there are credible reports that the current population of the city and surrounding area is up to

six million, slightly less than twenty per cent of the estimated population of Afghanistan. Kabul is the largest

city in central Asia.

2.3

The city’s rapid growth has put pressure on its infrastructure including roads, water, sanitation and

electricity supply. Some ‘formal’ areas of Kabul city were laid out under a master plan developed in 1978.

These areas are generally closer to the city’s centre, mostly in the east and north, and tend to have better

access to infrastructure.

2.4

Up to seventy per cent of the city consists of ‘informal’ areas, which are not part of the master plan

and have typically been developed and settled with the permission of landowners. These areas make up the

great majority of Kabul’s urban landscape. The quality of housing and infrastructure in informal areas varies

greatly and includes many areas of basic housing with unreliable access to infrastructure.

2.5

In addition, there are a number of ‘illegal’ areas in the city which consist of communities that have

been settled without the permission of the landowner. There are approximately 50 such sites in Kabul with

33,000 residents. Many of these are on public land and on hillsides throughout Kabul. Living conditions in

Kabul’s illegal settlements are particularly difficult. This is due in part to their insecurity of land tenure which

makes it difficult for residents to build more permanent shelters. Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) are

often prevented by Government authorities from providing sanitation and other services to these

communities as an incentive for them to return to their areas of origin in other provinces. Government

authorities and private owners sometimes threaten to evict individuals illegally occupying land in and around

Kabul.

Recent History

2.6

Following the collapse of the Soviet–backed Najibullah Government in 1992, the mujahedeen seized

Kabul and declared it the ‘Islamic State of Afghanistan’. During the ensuing civil war, much of Kabul was

destroyed in fighting. The Taliban takeover of Kabul in 1996 led to a period of neglect and under-investment

in urban infrastructure. Following al-Qaeda’s 2001 attacks on targets in the United States, international

forces led by the US launched Operation Enduring Freedom, removing the Taliban from power and taking

Kabul in November 2001.

2.7

Since then, Kabul has grown rapidly from a population of 500,000. This growth is due in part to the

return of refugees from other countries and the arrival of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) from other

parts of Afghanistan due to conflict and natural disasters. Relatively good economic opportunities and a

greater level of security are also important factors in Kabul’s growth.

Economic Overview

2.8

Kabul’s economy is based on trade and other service industries. There is some agriculture in the

areas around Kabul city. In addition, a small number of larger private businesses have set up facilities in and

around Kabul, including in food processing, textile production and light manufacturing.

DFAT Thematic Report - Conditions in Kabul

5

2.9

Since 2001, economic growth in Kabul has been driven by unprecedented inflows of international

assistance as well as the substantial presence of international forces and international organisations with

offices in the city. However, the gradual drawdown of international forces may already have had a negative

impact on the economy of Kabul. As the capital of Afghanistan, Kabul also hosts a number of central

Government ministries and institutions which make a significant contribution to the economy of the city.

2.10 The concentration of international forces, international organisations and government ministries has

meant that the cost of living is relatively high in Kabul. Rents in Kabul tend to be expensive compared to

most other parts of Afghanistan. As a result, many who live in Kabul may have no other option than to live in

informal settlements. Many poorer residents are forced to borrow money to survive, entering a cycle of

poverty and indebtedness.

2.11 A wide range of commercial services are available in Kabul. These include small family markets,

vegetable markets, butchers, clothes markets, home-ware stores, mobile phone shops and petrol stations.

Kabul’s role as a trading hub generally means that most types of produce available elsewhere in Afghanistan

are also available in Kabul.

Employment

2.12 Because of the city’s size and growth, Kabul offers a greater range of employment opportunities than

many other areas of Afghanistan. Employment growth has been strongest in Kabul’s service sector,

particularly in the construction industry and in small businesses such as family-owned markets. Due to the

significant military and government presence in Kabul, there are also some employment opportunities in the

armed forces or civil service.

2.13 Although there are no reliable statistics, unemployment is widespread in Kabul and

underemployment is also common. The influx of IDPs and returnees in the city has put pressure on the local

labour market. Those who have foreign language and computer skills tend to be best placed to find well-paid

employment in Kabul. New arrivals to Kabul from rural areas tend to be at a disadvantage due to their lack

of skills in demand. Many of these new arrivals also lack a network of family contacts needed to find

employment. In this situation, employment may be irregular and often insecure–many work as relatively

poorly paid day labourers who seek occasional work as it becomes available. Others are required to beg or

work as street-sellers.

2.14 Although it is difficult for women to find employment in Kabul, there tend to be more opportunities in

Kabul compared to other parts of Afghanistan. However, female-headed households with no additional family

support tend to be among the most economically vulnerable groups in Kabul.

Education

2.15 Educational facilities and access to education, particularly for girls, have improved greatly since

2001, and tend to be better in Kabul than in other areas of Afghanistan. For many new arrivals, access to

education has been a key factor in their decision to move to Kabul. Because of the relative quality of

education options in Kabul, some families in other parts of Afghanistan send their children to Kabul for

courses during the winter.

2.16 In general, public education is free and available to most families in Kabul, but tends to be over-

subscribed. Some children do not attend school because they are required to work instead. A survey by

Afghanistan’s Centre for Policy and Human Development in 2011 estimated that 65 per cent of children in

Kabul were enrolled in primary or secondary education, higher than the national average of 46 per cent.

2.17 The Hazara community operates a number of private schools in Kabul. For at least some of these

schools, there are good facilities, teacher training and educational outcomes for students, demonstrated by

very high university acceptance rates.

2.18 Kabul also hosts a number of Afghanistan’s most highly regarded higher-educational facilities,

including Kabul University and the Kabul Polytechnic University.

Health care

2.19 The health care system in Afghanistan has improved greatly since 2001. Basic public health care is

free, but demand for public health care continues to exceed supply. Medical facilities in the public system,

while still basic, tend to be better in Kabul than in other areas of Afghanistan. Better quality services are

provided by private practices, but many residents cannot access these services because of their high cost.

6

DFAT Thematic Report - Conditions in Kabul

2.20 In addition to primary health care services, a number of specialist services are available, including

emergency services, cardiac care and pathology laboratories. Kabul lacks some specialist treatment options

for chronic, complex and life-threatening conditions. As a result, relatively wealthy patients often choose to

travel abroad for specialist treatment. Most, however, cannot afford to do this and the high morbidity and

mortality rates in part reflect the lack of access to specialist care.

Utilities

2.21 Access to electricity is highly variable, even in formal areas of the city. Electricity ‘load shedding’ and

blackouts are common. For many in Kabul’s informal areas, electricity is supplied by a community generator

for which a fee is charged by the operator, a relatively expensive form of supply. According to the World Bank

and United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), although most established residents had

access to some electricity, up to 84 per cent of IDPs lacked access to any electricity.

2.22 Most informal and illegal areas do not have reliable access to municipal water supply, relying instead

on wells and water deliveries. Sanitation in these areas tends to be poor. Waste collection is better in

informal areas than illegal areas. Many communities burn their waste which contributes to Kabul’s air

pollution.

Religious facilities

2.23 There are a number of Sunni and Shia mosques in Kabul. There are some religious facilities for

Christians in Kabul that are generally available only to non-Afghans. There are also a number of religious

facilities for Hindus and Sikhs. Many non-Muslims do not openly practise their religion because of the risk of

discrimination or violence.

2.24 A bombing attributed to Pakistan-based Lashkar-e Jhangvi (LeJ) of the Shia Abu Fazl mosque in

Kabul during Moharram in December 2011 reportedly killed at least 70 people. However, DFAT assesses

that this was an isolated incident and that it is unclear whether it was the result of sectarian tensions. DFAT

assesses that Sunni-Shia sectarian violence is infrequent in Kabul.

Land issues

2.25 Land ownership in Kabul remains a source of tension particularly between existing residents and

new arrivals. The situation is complicated by the absence of formal land records, changes of regime since

1978 and the distribution of land according to patronage by those in power since 2001. Some returnees to

Kabul may have difficulty obtaining legal title to their land or may find their land has been illegally occupied.

DFAT is aware of at least one case in which IDPs were arrested and evicted from an illegally occupied site in

Kabul at the request of the land-owner. The land-owner reportedly paid compensation to those evicted.

2.26 Ethnicity may also be a factor in tension over land issues in Kabul. IDPs and recent arrivals generally

seek co-location with their tribal counterparts, causing localised overcrowding when large groups arrive in

Kabul at the same time. Given limited space, expansion by one family is often at the expense of another. As

a result, those on the fringes of a community often encroach on other ethnic groups.

Security Situation

2.27 Insurgents regularly conduct high-profile attacks in Kabul. DFAT assesses that the primary targets for

insurgent attacks are government institutions, political figures, Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF),

International Security Assistance Forces (ISAF), other security services and international organisations. Such

attacks often cause significant casualties amongst civilian bystanders in addition to those being specifically

targeted.

2.28 Representative examples include the suicide bomb attack against the Supreme Court in Kabul in

June 2013 which killed 17 and injured 39 others; a complex attack by insurgents against a restaurant in

Kabul during January 2014 which killed at least 21 people, including 13 foreigners; and an attack on the

Kabul Serena Hotel in March 2014 which killed at least nine people, including four foreigners. Kabul

International Airport has been attacked on a number of occasions, including most recently in July 2014.

2.29 The ANSF and international forces have put in place a range of counter-measures to prevent and

respond to insurgent attacks in Kabul. There are numerous checkpoints along highways leading to Kabul, at

major intersections and at government and international institutions within Kabul. These provide a strong

DFAT Thematic Report - Conditions in Kabul

7

deterrent to insurgent attacks by increasing the risk that insurgents will be detected prior to undertaking

attacks in Kabul. ANSF and international forces concentrated in Kabul are also quick to respond to insurgent

attacks when they occur. For example, the ANSF provided a rapid and effective response to an insurgent

attack against Kabul airport in June 2013.

Security for women and girls in Kabul

2.30 According to the United Nations’ Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), during 2013 there

were 255 cases registered by police and 968 cases registered by prosecutors in Kabul under the Law on the

Elimination of Violence against Women. UNAMA notes that the relatively high number of cases should be

‘assessed in the context of Kabul as the most highly populated province in Afghanistan’. Without

comprehensive census figures, it is difficult to determine whether these numbers represent a higher-level of

comparative reporting.

2.31 DFAT assesses that, although women and girls in Kabul may be subject to some kinds of violence,

particularly domestic violence, there tends to be a higher level of security for them in Kabul than in many

other parts of Afghanistan (see also the March 2014 DFAT Country Report on Afghanistan).

8

DFAT Thematic Report - Conditions in Kabul

3. Other Considerations

State Protection

3.1 Overall, DFAT assesses that the Government maintains effective control of Kabul, due to a range of

counter-measures put in place to prevent and respond to insurgent attacks. The relatively high level of state

protection available in the city, including in formal, informal and illegal areas, has been an important driver

of large-scale urban migration to Kabul since 2001.

Police

3.2 The Afghan National Police (ANP) has primary responsibility for internal law and order, including in

Kabul, and plays an active role in fighting insurgent groups. Policing in Kabul tends to be more effective than

in most other urban and rural areas, but as in many poorer nations, the capacity of the ANP to maintain law

and order is limited by a lack of resources, poor training, insufficient and outmoded equipment and political

manipulation.

3.3 In many cases, individuals needing protection may be reluctant to seek protection from the police.

This may be due in part to residents’ lack of confidence in the police’s ability to protect them, the difficulty

police will have in prosecuting offenders through the judicial system, and also to credible allegations of

corruption among the police.

Judiciary

3.4 The formal judicial system is hampered by underfunding and a lack of qualified and properly trained

judges and lawyers. Although the formal justice system is relatively strong in Kabul, like the ANP, it has

faced credible allegations of corruption and it lacks the capacity to process a large number of cases in a

timely way. Outside of the formal justice system, traditional justice mechanisms are also used to deal with

grievances and disputes in Kabul.

3.5 Attacks and threats against judges and lawyers carried out by insurgents, including the June 2013

attack against the Supreme Court in Kabul, undermines the formal judicial system.

Internal Relocation

3.6 Large urban areas in Afghanistan are home to mixed ethnic and religious communities and offer

greater opportunities for employment, access to services and a greater degree of state protection than many

other areas. As Afghanistan’s largest urban centre, Kabul provides the most viable option for many people

for internal relocation and resettlement in Afghanistan. This applies to those internally displaced by conflict

and natural disasters, economic migrants and returnees to Afghanistan. This movement to Kabul is largely

the result of economic opportunity, but it is often difficult to differentiate between economic migrants and

those internally displaced as a result of conflict or natural disasters.

Government policy on internal relocation

3.7 Article 39 of Afghanistan’s Constitution guarantees Afghans’ rights to ‘travel and settle in any part of

the country, except in areas forbidden by law’. Presidential Decree 104 of 2005 stipulates that all IDPs and

returnees should return to their place of origin or an adjacent province. The Government’s Ministry of

Refugees and Repatriation (MORR) has allocated plots of land in these areas for resettlement. In practice,

this policy has meant the Government has been reluctant to provide greater services for IDPs and returnees

in Kabul. Despite this, many choose to remain in Kabul or are unable to return to their areas of origin.

DFAT Thematic Report - Conditions in Kabul

9

Ethnicity

3.8 Traditional extended family and tribal community structures of Afghan society can be an important

protection and coping mechanism for IDPs. Many Afghans who are IDPs rely on these networks for their

safety and economic survival, including access to accommodation and an adequate level of subsistence.

3.9 Kabul’s size and diversity means that there are large communities of almost all ethnic, linguistic and

religious groups present in the city. Given the growth of Kabul’s population since 2001, many individuals

may have members of their extended family in Kabul who can assist with their relocation.

3.10 DFAT assesses that there are generally options available for members of most ethnic and religious

minorities to be able to relocate from other parts of Afghanistan to relative safety in Kabul.

Anonymity

3.11 The growth of Kabul’s population since 2001 and the absence of a single, central register of

addresses has provided a higher level of anonymity for new arrivals. Because ethnic groups tend to live

homogenously within Kabul, anonymity is more possible between members of different ethnic groups than it

is within particular ethnic groups. The possibility of greater anonymity may encourage individuals and

families to seek protection in Kabul.

3.12 DFAT assesses that because of its size and diversity, individuals may be more likely to be able to

remain anonymous in Kabul than in rural areas or smaller urban areas, particularly if they maintain a low

profile.

Other factors affecting internal relocation

3.13 In practice, DFAT assesses that a lack of financial resources and lack of employment opportunities are

the greatest constraints on successful internal relocation. This is compounded by Kabul’s relatively high cost

of living, particularly the cost of housing.

3.14 Internal relocation to urban areas is generally more successful for single men of working age.

Unaccompanied women and children are least likely to be able to relocate to urban areas without the

assistance of family or tribal networks.

Treatment of Returnees

3.15 At present, all involuntary and most voluntary returnees from Western countries are returned to Kabul.

A high proportion of returnees choose to remain in Kabul rather than return to other places of origin. DFAT

assesses that because of Kabul’s size and diversity, returnees would be unlikely to be discriminated against

or subject to violence on the basis of ethnicity or religion.

3.16 Returnees generally have lower household incomes and higher rates of unemployment than

established community members. However, DFAT assesses that the situation for returnees to Kabul provided

with cash or in-kind reintegration assistance tends to be more favourable than for IDPs who do not receive

this level of assistance. Such reintegration programs offered by the International Organization for Migration

(IOM) and others can include the provision of vocational and other training, assistance to help establish

businesses and cash grants.

3.17 Men of working age are more likely to be able to return and reintegrate successfully than

unaccompanied women and children without the assistance of family or tribal networks. Although women in

Afghanistan continue to experience pervasive discrimination and violence in most aspects of daily life, there

tend to be more opportunities for women in Kabul than in many other parts of Afghanistan (see also the

March 2014 DFAT Country Report on Afghanistan).

10

DFAT Thematic Report - Conditions in Kabul