1

MONETARY POLICY NEAR THE ZERO LOWER BOUND

(2015) finds that there is a 14 per cent probability of the cash rate being at zero by

February 2017.

(2015) finds a 14 per cent probability that the cash rate will reach zero by February 2017.

D15/127109

GENERAL

1

Economist

Research

Economic Research Department

21 April 2015

D15/127109

GENERAL

2

Resources

M (2015), ‘Estimates of Uncertainty around the Market-implied Cash Rate Path’,

ER internal

note.

D15/127109

GENERAL

3

2

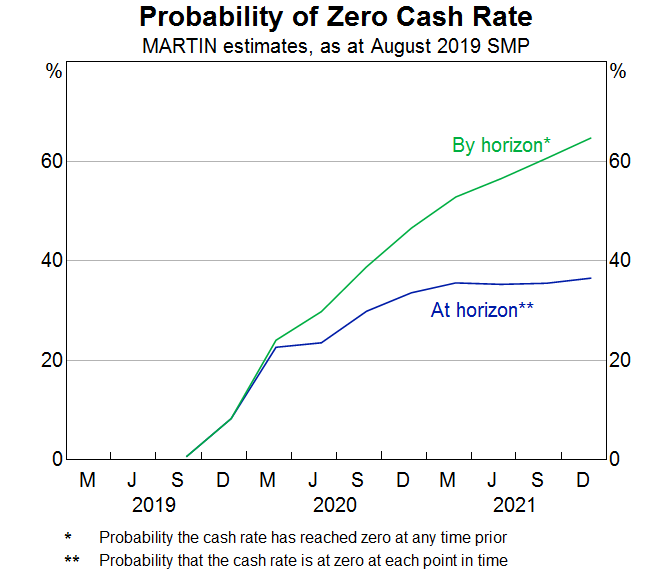

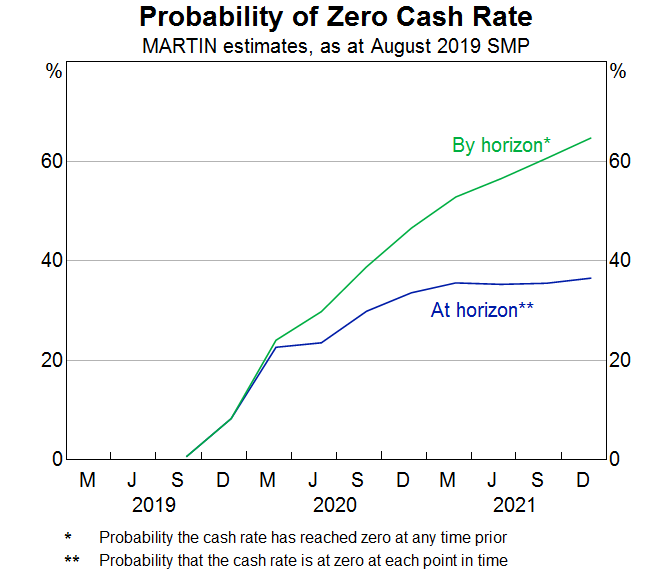

THE PROBABILITY OF REACHING THE ZERO LOWER BOUND

If forward rates make the same size errors as they have in the past, there is a 41 per cent probability of a zero

cash rate at December quarter 2021. Stochastic simulations of MARTIN imply a similar probability of

37 per cent.

The August SMP assumed the cash rate will decline to 42 basis points by mid‐2021. This raises the prospect

that monetary policy could soon be constrained by the zero lower bound (ZLB), limiting the ability of

monetary policy to offset future negative shocks.

(2015) calculates the distribution of historic errors in market expectations of the cash rate at different

horizons (Graph 1). Assuming the market makes similarly sized errors to those in the past gives the probability

that the cash rate will be constrained at the ZLB. Updated estimates using this approach are shown as the

orange line in Graph 2. The probability of reaching the ZLB is estimated to be 34 per cent at December 2020,

and 41 per cent at December 2021. The blue line in Graph 2 shows the probability of reaching the ZLB using

stochastic simulations in MARTIN (

forthcoming). 1

Graph 1

Graph 2

Cash Rate and Market-implied Path

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

Quarterly

As at August 2019 SMP

%

%

%

%

10

10

Forward rate errors

40

40

8

8

30

30

MARTIN

6

6

(preliminary)

Zero-coupon

forward rate

20

20

4

4

Cash rate target

10

10

2

2

Aug SMP projection

0

0

0

0

1996

2001

2006

2011

2016

2021

M

J

S

D

M

J

S

D

M

J

S

D

Source: RBA

2019

2020

2021

Source: RBA

The two approaches have different strengths and weaknesses. MARTIN’s estimates depend on many

assumptions and estimates. In particular, they assume that the cash rate follows a calibrated Taylor‐type rule

(see

&

2018) which is a very simple approximation to past RBA behaviour. The yield curve

approach assumes that the OIS curve makes the same size errors as it has in the past. In contrast to MARTIN,

forward rates should encompass all available information. Accordingly, unless one thought that forward rates

are seriously biased or misinformed, yield curve errors provides more credible point estimates of the

probability than MARTIN’s stochastic simulations. However, the two big advantages of using MARTIN are that

it enables estimation of how alternative policies might interact with the ZLB, and can quantify the costs of

constrained monetary policy (for example, in terms of additional unemployment). Both issues are discussed

in more detail in

(forthcoming). That said, the most important point is that both methods produce

very similar results, despite being constructed independently.

These results have important policy implications – if the probability of a zero cash rate is high, monetary

policy should arguably be more expansionary than would otherwise be the case, as discussed in

2015,

2016 and

2015).

Research Economist

Economic Research Department

21 August 2019

1 Thanks to

for helpful comments and running the MARTIN simulations.

D19/374060

GENERAL

1

Appendix A ‐ Measurement details

Following

(2015), I use zero‐coupon forward rates as a measure of market expectations for the path of

the cash rate. These forward rates are constructed using overnight index swap (OIS) rates, and yields on

Treasury notes and Commonwealth Government Securities. To calculate historic errors in cash rate

expectations, I take the market‐implied path of the cash rate on the first Wednesday of the months in which

the SMP is released. This should approximately reflect the cash rate expectations on which the Bank’s

forecasts have been conditioned. The cash rate `forecast error’ is then defined as the realised cash rate target

minus the corresponding zero‐coupon forward rate. I use EA’s cash rate assumption from the August SMP as

the baseline cash rate path.

In calculating the probabilities presented in this note I have used historic

absolute forward‐rate errors. Doing

so assumes that the forward curve is an unbiased forecast of the cash rate. An alternative approach could be

to assume that the cash rate forecast errors follow the same distribution as the historical distribution of

actual forecast errors. Under this approach, the probability of zero cash rate at December quarter 2021 is

60 per cent.

D19/374060

GENERAL

2

link to page 6

3

THE EFFECTIVE LOWER BOUND AND ITS IMPLICATIONS

As the cash rate declines, the possibility of reaching its Effective Lower Bound (ELB) becomes a more

pressing concern. Stochastic simulations in MARTIN show that the likelihood of a zero cash rate in December

2021 has risen to around 40 per cent as at the August 2019 SMP from around 20 per cent at the May 2019

SMP.

Introduction

In this note I estimate the probability of reaching the ELB using MARTIN, incorporate an ELB in to MARTIN’s

policy rule and discuss some of the implications of being constrained by the lower bound.

Probability of reaching the ELB

Stochastic simulations in MARTIN estimate that the likelihood of reaching an ELB is relatively high and has

increased recently

(Graph 1).3 For example, there is a 37 per cent chance of being at the zero lower bound

at the end of the forecast horizon, according to MARTIN. This estimate was just 18 per cent at the May 19

SMP. Non-parametric methods using market pricing produce similar results (

2019). If we measure

the probability of having reached a cash rate of zero by the forecast horizon, instead of necessarily being at

zero at the forecast horizon, the estimate is around 60 per cent.

Graph 1

.

3 I use 10,000 draws of historical errors, apply these errors as shocks to MARTIN and measure how many of the scenarios result

in a cash rate at or below 0. See

2019 for more detail on stochastic simulations in MARTIN.

D19/196145

GENERAL

1

Limitations and further work

This work abstracts from agents’ expectations of future monetary policy, which are likely to be an

important element when the central bank is constrained by the ELB. Further work will look to incorporate

expectations into the ELB framework presented in this note.

Conclusion

Stochastic simulations in MARTIN show that the likelihood of a zero cash rate in December 2021 has risen

in recent months to around 40 per cent as at the August 2019 SMP. Simple

Macroeconomic Modelling

Economic Analysis Department

8 October 2019

D19/196145

GENERAL

6

link to page 8

4

ESTIMATES OF UNCERTAINTY AROUND THE MARKET-IMPLIED CASH RATE PATH

This note estimates the uncertainty around a market-implied path of the cash rate using the historical

distribution of differences between zero-coupon forward rates and the actual cash rate target. The width of

the estimated 90 per cent confidence interval is about ±3 percentage points at the two-year horizon. If the

distribution of forward-rate errors is similar to that over the past two decades, the market path at the time

of the February SMP implies that the probability of a zero cash rate in February 2017 is 14 per cent.

Introduction

Forecasts presented in the February Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP) were conditioned on the

assumption that the cash rate moves broadly in line with expectations inferred from market pricing.1 While

the SMP was careful to stress that ‘this assumption does not represent a commitment by the Board to any

particular path for policy’, it may be desirable to reinforce this point. One way of doing this is by graphically

presenting confidence intervals around the market-implied cash rate path (i.e. the cash rate ‘forecast’), as

is done for the SMP forecasts of GDP growth, inflation and, more recently, unemployment. Additionally,

estimates of uncertainty around the cash rate forecast can be used to estimate the probability of the cash

rate reaching zero, which may be an important consideration when determining the appropriate path of

policy.2

Some other central banks present measures of uncertainty around their policy rate projections. For

example, the US Federal Reserve publishes model-based confidence intervals and the distribution of

Federal Open Market Committee participants’ projections of the appropriate path of the federal funds rate.

The Riksbank publishes a forecast repo rate path, with confidence intervals based on the Riksbank’s own

forecasting errors and the historical ability of forward rates to forecast the repo rate (Kjellberg and Villani

2010; Sveriges Riksbank 2015).3 Norges Bank publishes forecasts of the ‘key policy rate’ based on

judgement about the appropriate path of monetary policy, with confidence intervals generated using a

macroeconomic model (Norges Bank 2005, 2014).

Graph 1

Cash Rate and Market-implied Path

Data and methodology

Quarterly

%

%

I use estimated zero-coupon forward rates as a

measure of market expectations for the path of the

10

10

cash rate

(Graph 1). These forward rates are

Zero-coupon

forward rate

constructed using overnight index swap (OIS) rates,

8

8

and yields on Treasury notes and Commonwealth

Government Securities.4 For the purposes of this

6

6

analysis, the market-implied path of the cash rate

4

4

is taken as being the zero-coupon forward curve on

Cash rate target

the first Wednesday of the months in which the

2

2

SMP is released (i.e. the day after the Board’s cash

rate decision), as this should be a reasonable

0

0

approximation of the cash rate expectations on

1993

1999

2005

2011

2017

which the Bank’s SMP forecasts could be

Source: RBA

conditioned. The realised cash rate target is taken to be the cash rate target on the same days. The cash

rate ‘forecast error’ is defined as the realised cash rate target minus the corresponding zero-coupon

1 In previous SMPs, forecasts were conditioned on the assumption of a constant cash rate.

2

(forthcoming) reviews the literature discussing the appropriate setting of monetary policy given the existence of a

lower bound on nominal interest rates.

3 The Riksbank uses two sources of forecasts errors because the history of its own forecasts is too short to precisely estimate

confidence intervals around the repo rate projection.

4 There are three main sources of data used by the Bank to infer market-implied cash rate expectations: interbank cash rate

futures (e.g. Figure 4.1 of the

February SMP); OIS (e.g. DM Monthly Note – March 2015); and estimated zero-coupon forward

rates (e.g.

Statistical Table F17, Finlay and Chambers (2008) and Finlay and Olivan (2012) – see these papers for details on how

the zero-coupon forward rates are estimated). Differences between cash rate expectations implied by these data sources

appear to be small. I use zero-coupon forward rates because of their longer horizon and availability from an earlier date.

D15/126403

1

link to page 9 link to page 9

forward rate. Cash rate forecast errors are calculated at quarterly horizons up to nine quarters ahead over

the inflation-targeting period.

Summary statistics

Table 1 presents statistics describing cash rate forecast errors. The market-implied cash rate path appears

to be roughly unbiased at short horizons, but the size of the average error (or bias) increases with the

horizon (although it is not significantly different to zero at the 5 per cent level of significance at forecast

horizons less than eight quarters ahead). The bias at longer horizons could reflect the existence of a

positive term premium (discussed below). The average magnitude of errors, as measured by the mean

absolute error (MAE) and root-mean-square error (RMSE), also increases with the forecast horizon.

Table 1: Cash Rate Forecast Errors Based on Zero-coupon Forward Rates – Summary Statistics

Percentage points

Forecast horizon

One quarter

Two quarters

Four quarters

Eight quarters

0.04

−0.06

−0.21

−0.67

Average error(a)

(0.22)

(0.48)

(0.26)

(0.03)

MAE

0.23

0.39

0.81

1.39

RMSE

0.34

0.64

1.07

1.56

Maximum absolute error

1.59

3.36

3.64

3.84

Forecast origin

August 2008

August 2008

May 2008

February 1995

No. of observations

86

85

83

79

(a) p-values (in brackets) based on a constant-only regression with Newey-West standard errors

Source: RBA

Confidence intervals

Graph 2 presents the 70th and 90th percentiles of the historical distribution of absolute forecast errors.5 As

expected, the percentiles tend to increase with the forecast horizon; the 90th percentile of absolute four-

quarter-ahead forecast errors is around 1.7 percentage points, while it is around 2.9 percentage points at

the eight-quarter-ahead horizon. Using the distribution of

absolute forecast errors to construct confidence

intervals assumes that the distribution of forecast errors is symmetric and centred at zero; that is, it

assumes that any bias and skewness in the sample of forward-rate errors will not persist into the future (it

is not necessary to assume normality). These are the same assumptions made in constructing the

confidence intervals presented in the SMP.

Graph 2

Graph 3

Cash Rate Forecast Confidence Intervals*

Cash Rate Forecast*

Percentiles of absolute forecast errors since 1993

Quarterly

ppt

ppt

%

%

90th percentile

70 per cent

interval

2

2

4

4

70th percentile

1

1

2

2

0

0

90 per cent interval

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

0

Horizon: quarters from forecast origin

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

* Forecasts based on zero-coupon forward rates

* Based on zero-coupon forward rates

Source: RBA

Source: RBA

5 This choice of percentiles matches those used in constructing the confidence intervals presented in the SMP.

D15/126403

2

link to page 9 link to page 10

Graph 3 shows the market-implied cash rate path as at the February 2015 SMP, along with the

70 and 90 per cent confidence intervals based on the distribution of absolute forecast errors. The intervals

are substantially wider than some alternatives. For example, the 90 per cent probability interval around the

Economic Research (ER) model-based cash rate forecast is around ±2 percentage points at the two-year

horizon, although this partly reflects the fact that this interval is based on in-sample fit, rather than on

historical out-of-sample forecasting performance.6 The market-implied intervals are also probably wider

than some people’s subjective assessment of current uncertainty around the path of the cash rate.

However, psychological studies find that subjective estimates of uncertainty tend to be too low (often by

large margins), even among experts.7

In presenting the confidence intervals, I truncate them at zero, consistent with the approach taken by

Norges Bank (Norges Bank 2014).8 However, in reality the effective lower bound on the nominal policy rate

may be different to zero for technical reasons. For example, the Fed and Bank of England have positive

effective lower bounds, while the Riksbank and the Swiss National Bank currently have negative policy

rates. In contrast to the approach taken here, the Riksbank does not truncate its repo rate forecast

distribution at a lower bound, so that the forecast distribution has considerable probability mass at repo

rates as low as −2 per cent (Sveriges Riksbank 2015). This may strike some readers as implausible. However,

Kjellberg and Villani (2010) argue that this can be justified in two ways: 1) the zero lower bound is not

exactly zero, implying that moderately negative interest rates cannot be ruled out; and 2) negative policy

rates in the forecast distribution can be taken to represent alternative monetary policy measures with the

same effect as though the policy rate were negative.

Probability of reaching the zero lower bound

Graph 4

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

The intersection of the horizontal axis and the

As at February 2015 SMP

confidence intervals in Graph 3 provides an

%

%

estimate of the probability of a zero cash rate at a

Based on historical distribution

of forecast errors

given forecast horizon, conditional on the market-

30

30

implied cash rate path at the time of the February

SMP. The pink line in

Graph 4 shows this

20

20

probability at different forecast horizons, assuming

that the distribution of absolute forward-rate

errors is the same as over the past two decades

10

10

and that these errors are symmetrically distributed

Based on historical

distribution of

absolute

around zero. The market path implies that the

forecast errors

0

0

probability of the cash rate being at the zero lower

May-15

Nov-15

May-16

Nov-16

May-17

bound is 5 per cent in February 2016 and 14 per

Horizon

cent in February 2017.

* Based on zero-coupon forward rates

Source: RBA

Using absolute errors assumes that the forward curve provides an unbiased forecast of the cash rate. As

mentioned above, this assumption is also made in constructing the SMP confidence intervals, although the

rationale differs here. Tulip and Wallace (2012) argue that any bias in economic forecasts should not persist

into the future, since it is in the forecaster’s interest to generate unbiased forecasts. However, in the case

of the cash rate, this assumption is equivalent to assuming that any term premia in the zero-coupon

forward rates are zero on average. However, this might not be the case if investors require (or a willing to

pay) a premium for holding longer-maturity assets.

An alternative approach is to assume that cash rate forecast errors follow the same distribution as the

historical distribution of

actual forecast errors. This allows the forecast error distribution to have a mean

equal to the average forward-rate error, which can be interpreted as the average term premium. It also

preserves the historical skewness in the data. Under this approach, shown as the purple line in Graph 4, the

6 See Graph 3 in

and

(2015) (restricted).

7 See Kahneman, Slovic and Tversky (1982) (Part VI, titled ‘Overconfidence’) or, for an accessible summary, the Wikipedia (2012)

entry ‘Overconfidence Effect’.

8 Truncation means that forward rates represent the median but not the mean of the cash rate forecast distribution, since the

truncated distribution is asymmetric. However, the expectations theory of the yield curve implies that forward rates should

equal the mean. I ignore this complication here, but recognise that it would need to be addressed in further work.

D15/126403

3

link to page 11

probability of a zero cash rate is estimated to be 9 per cent in February 2016 and 27 per cent in

February 2017. These probabilities are substantially higher than those based on the historical distribution

of absolute forecast errors, because the sample includes more large negative forecast errors (i.e. where the

realised cash rate turned out to be substantially lower than forecast) than large positive forecast errors

(Graph 5).

Graph 5

Although the purple line in Graph 4 is simpler to

Histogram of Cash Rate Forecast Errors*

construct and explain, and requires fewer

Relative frequency, eight-quarter-ahead horizon

assumptions, the pink line will be more valid if the

%

%

apparent bias in the market-implied path at longer

horizons has arisen by chance and is likely to

20

20

disappear. Consistent with this, Finlay and

Chambers (2008) find evidence to suggest that

15

15

term premia at maturities up to five years were

small and

negative through most of the inflation-

10

10

targeting period up to 2007 (although they were

positive and relatively large in the mid 1990s,

5

5

which coincides with several large negative cash

rate forecast errors). Additionally, the cash rate

0

0

expectations presented in the DM Monthly Note

<-3

-3 to -2 -2 to -1 -1 to 0

0 to 1

1 to 2

2 to 3

>3

and the SMP are not adjusted for term premia.9

* Based on zero-coupon forward rates

Source: RBA

Stability of uncertainty measures

The estimates in this note are conditional on the shocks experienced during the inflation-targeting period,

but this may not be representative of the shocks that will be experienced in the future. Specifically, there

may be periods when the path of the cash rate is more or less uncertain (i.e. the cash rate forecast errors

could be heteroskedastic). This might be the case if, for instance, the Bank’s communications and policy

reaction function have become clearer, so that market participants are better able to predict the path of

the cash rate, or if the variance of economic shocks has declined.

As a rough test of the stability of the variance of the forecast error distribution, I regress the squared cash

rate forecast errors on a constant and a dummy variable that is equal to one after the Bank began explicitly

publishing its forecasts in the SMP (February 2007). I use Newey-West standard errors to account for

autocorrelation. I am unable to reject the null hypothesis that the coefficient of the dummy variable is

equal to zero at any of the forecast horizons considered, suggesting that improvements in the Bank’s

communication have not improved the market’s ability to forecast changes in the cash rate. However, this

test is fairly rudimentary and the results are sensitive to the exclusion of the large forecast errors arising

during the global financial crisis. At face value, the results provide little evidence to suggest that the

variance of the forecast error distribution, and thus the width of the confidence intervals, has changed over

time.

Conclusion

As the discussion above indicates, different assumptions about bias, skewness, stability and so on could be

made in estimating uncertainty about the market-implied cash rate path. Although these would change

numerical estimates, they are unlikely to greatly change the qualitative results. Specifically, uncertainty

about the future cash rate is large (arguably, this is the key point that publication of confidence intervals

needs to convey) and the probability of hitting the zero lower bound is substantial.

Economist

Economic Research Department

14 April 2015

9 Some central banks adjust forward rates for the existence of risk premia. For example, the Fed uses a rule-of-thumb that the

term premium is equal to one basis point per month (e.g. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2009). Up to

September 2008, the Riksbank adjusted forward rates at each horizon by subtracting the average forward-rate error (Kjellberg

and Villani 2010). Since then, the Riksbank has adjusted forward rates by subtracting model-based estimates of risk premia.

D15/126403

4

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2009), Monetary Policy Alternatives, December.

Finlay R and M Chambers (2008), ‘A Term Structure Decomposition of the Australian Yield Curve’, RBA

Research Discussion Paper No 2008-09.

Finlay R and D Olivan (2012), ‘Extracting Information from Financial Market Instruments’, RBA

Bulletin,

March, pp 45–54.

Kahneman D, P Slovic and A Tversky (eds) (1982), Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Kjellberg D and M Villani (2010), ‘The Riksbank’s Communication of Macroeconomic Uncertainty’, Sveriges

Riksbank

Economic Review, 1, pp 5–41.

D (forthcoming), ‘Monetary Policy near the Zero Lower Bound’, internal ER note.

Norges Bank (2005), ‘Uncertainty Surrounding Future Interest Rate Developments’,

Inflation Report,

3/2005, pp 19–21.

Norges Bank (2014), Monetary Policy Report, 4/2014.

Sveriges Riksbank (2015), Monetary Policy Report, February.

Tulip P and S Wallace (2012), ‘Estimates of Uncertainty around the RBA's Forecasts’, RBA Research

Discussion Paper No 2012-07.

Wikipedia (2012), ‘Overconfidence Effect’, accessed 10 January 2012.

D15/126403

5

5

ALTERNATIVE INTEREST RATE PATHS – APRIL 2015

Forecast targeting1

D15/145971

1

Given the market-implied cash rate path in the baseline scenario, and assuming that

uncertainty around this cash rate forecast is as estimated in

(2015), the probability of a zero cash rate

in two years’ time is 15 per cent (Graph 2).2

Graph 2

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

As at April 2015

%

%

15

15

10

10

5

5

0

0

Jul-15

Jan-16

Jul-16

Jan-17

Horizon

* Based on market-implied cash rate path and the historical ability of zero-

coupon forward rates to forecast the cash rate; assumes forecast errors

are symmetric

Source: RBA

and

/Economists/Economic Research Department/23 April 2015

2 This estimate assumes that cash rate forecast errors follow the same distribution as the historical distribution of

absolute

forecast errors (based on zero-coupon forward rates) and that these errors are symmetrically distributed around the cash rate

forecast; assuming that cash rate forecast errors follow the historical distribution of

actual errors results in a substantially

higher probability of the cash rate reaching zero.

D15/145971

2

6

ALTERNATIVE INTEREST RATE PATHS – JULY 2015

Forecast targeting

D15/259070

1

link to page 16

Given the market-implied cash rate path in the baseline scenario, and assuming that

uncertainty around this cash rate forecast is as estimated in

(2015), the probability of a zero cash rate

in two years’ time is 15 per cent (Graph 2).

2

Graph 2

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

As at July 2015

%

%

15

15

10

10

5

5

0

0

Oct-15

Apr-16

Oct-16

Apr-17

Horizon

* Based on market-implied cash rate path and the historical ability of zero-

coupon forward rates to forecast the cash rate; assumes forecast errors

are symmetric

Source: RBA

Economist/Economic Research Department/20 July 2015

2 This estimate assumes that cash rate forecast errors fol ow the same distribution as the historical distribution of absolute

forecast errors (based on zero-coupon forward rates) and that these errors are symmetrically distributed around the cash rate

forecast; assuming that cash rate forecast errors follow the historical distribution of actual errors results in a substantial y

higher probability of the cash rate reaching zero.

D15/259070

2

7

ALTERNATIVE INTEREST RATE PATHS – OCTOBER 2015

Forecast targeting

D15/386771

1

link to page 18

Given the market-implied cash rate path in the baseline scenario, and assuming that

uncertainty around this cash rate forecast is as estimated in

(2015), the probability of a zero cash rate

in early 2018 is about 15 per cent (Graph 2).

2

Graph 2

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

%

%

15

15

10

10

5

5

0

0

Jan-16

Jul-16

Jan-17

Jul-17

Horizon

* Based on market-implied cash rate path and the historical ability of zero-

coupon forward rates to forecast the cash rate; assumes forecast errors

are symmetric

Source: RBA

2 This estimate assumes that cash rate forecast errors fol ow the same distribution as the historical distribution of absolute

forecast errors (based on zero-coupon forward rates) and that these errors are symmetrically distributed around the cash rate

forecast; assuming that cash rate forecast errors follow the historical distribution of actual errors results in a substantial y

higher probability of the cash rate reaching zero.

Economist

Economic Research Department

21 October 2015

D15/386771

2

8

ALTERNATIVE INTEREST RATE PATHS – JANUARY 20161

Forecast targeting

D16/25458

1

Given the market-implied cash rate path in the

baseline scenario, and assuming that uncertainty around this cash rate forecast is as estimated in

(2015), the probability of a zero cash rate in early 2018 is about 15 per cent (Graph 2).

Graph 2

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

%

%

15

15

10

10

5

5

0

0

Apr-16

Oct-16

Apr-17

Oct-17

Horizon

* Based on market-implied cash rate path and the historical ability of zero-

coupon forward rates to forecast the cash rate; assumes forecast errors

are symmetric

Source: RBA

Economist

Economic Research Department

20 January 2016

D16/25458

2

9

ALTERNATIVE INTEREST RATE PATHS – APRIL 20161

Forecast targeting

D16/135645

1

Given the market-implied cash

rate path in the baseline scenario, and assuming that uncertainty around this cash rate forecast is as

estimated in

(2015), the probability of a zero cash rate in two years is 14 per cent (Graph 2).

Graph 2

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

%

%

15

15

10

10

5

5

0

0

Jul-16

Jan-17

Jul-17

Jan-18

Horizon

* Based on market-implied cash rate path and the historical ability of zero-

coupon forward rates to forecast the cash rate; assumes distribution of

forecast errors is symmetric

Source: RBA

/Economist/Economic Research Department/20 April 2016

D16/135645

2

10

ALTERNATIVE INTEREST RATE PATHS – JULY 20161

Forecast targeting

D16/254859

1

Given the market-implied cash rate path in the

baseline scenario, and assuming that uncertainty around this cash rate forecast is as estimated in

(2015),

the probability of a zero cash rate at the end of the forecast horizon is 21 per cent (Graph 2).

Graph 2

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

%

%

20

20

15

15

10

10

5

5

0

0

Oct-16

Apr-17

Oct-17

Apr-18

Oct-18

Horizon

* Based on market-implied cash rate path and the historical ability

of zero-coupon forward rates to forecast the cash rate; assumes

distribution of forecast errors is symmetric.

Source: RBA

Economic Research Department

20 July 2016

D16/254859

2

11

ALTERNATIVE INTEREST RATE PATHS – OCTOBER 2016

Forecast targeting

D16/391044

1

Given the market-implied cash rate path in the baseline scenario, and assuming that uncertainty around this

cash rate forecast is as estimated in

(2015), the probability of a zero cash rate at the end of the forecast

horizon is 21 per cent (Graph 2).

Graph 2

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

%

%

20

20

15

15

10

10

5

5

0

0

Nov-16

May-17

Nov-17

May-18

Nov-18

Horizon

* Based on market-implied cash rate path and the historical ability

of zero-coupon forward rates to forecast the cash rate; assumes

distribution of forecast errors is symmetric.

Source: RBA

Economic Research Department

19 October 2016

D16/391044

2

12

ALTERNATIVE INTEREST RATE PATHS – JANUARY 2017

Forecast targeting

D17/26813

1

Given the market-implied cash rate path, and

assuming that uncertainty around this cash rate forecast is as estimated in

(2015), the probability of a

zero cash rate at the end of the forecast horizon is 9½ per cent (Graph 2).

Graph 2

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

%

%

10

10

8

8

6

6

4

4

2

2

0

0

Apr-17

Oct-17

Apr-18

Oct-18

Apr-19

Horizon

* Based on market-implied cash rate path and the historical ability

of zero-coupon forward rates to forecast the cash rate; assumes

distribution of forecast errors is symmetric.

Source: RBA

Economic Research Department

25 January 2017

D17/26813

2

13

ALTERNATIVE INTEREST RATE PATHS – APRIL 2017

Forecast targeting

D17/124820

1

Given the market-implied cash rate path, and assuming that uncertainty around this cash rate forecast

is as estimated in

(2015b), the probability of a zero cash rate at the end of the forecast horizon is 9½

per cent (Graph 2).

Graph 2

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

%

%

10

10

8

8

6

6

4

4

2

2

0

0

Jul-17

Jan-18

Jul-18

Jan-19

Jul-19

Horizon

* Based on market-implied cash rate path and the historical ability

of zero-coupon forward rates to forecast the cash rate; assumes

distribution of forecast errors is symmetric.

Source: RBA

Economic Research Department

19 April 2017

D17/124820

2

14

ALTERNATIVE INTEREST RATE PATHS – JULY 2017

Forecast targeting

D17/248278

1

Given the market-implied cash rate path, and assuming that uncertainty

around this cash rate forecast is as estimated in

(2015b), the probability of a zero cash rate at the end of

the forecast horizon is 11 per cent (Graph 2).

Graph 2

Probability of Zero Cash Rate at Horizon*

%

%

10

10

8

8

6

6

4

4

2

2

0

0

Oct-17

Apr-18

Oct-18

Apr-19

Oct-19

Horizon

* Based on market-implied cash rate path and the historical ability

of zero-coupon forward rates to forecast the cash rate; assumes

distribution of forecast errors is symmetric.

Source: RBA

Economic Research Department

19 July 2017

D17/248278

2

Document Outline