FOI 24/25-2259

Contents

Circles of Support and Microboards: Results of an environmental scan

1

Contents

2

Disclaimer

5

Acknowledgements

5

Suggested Citation

5

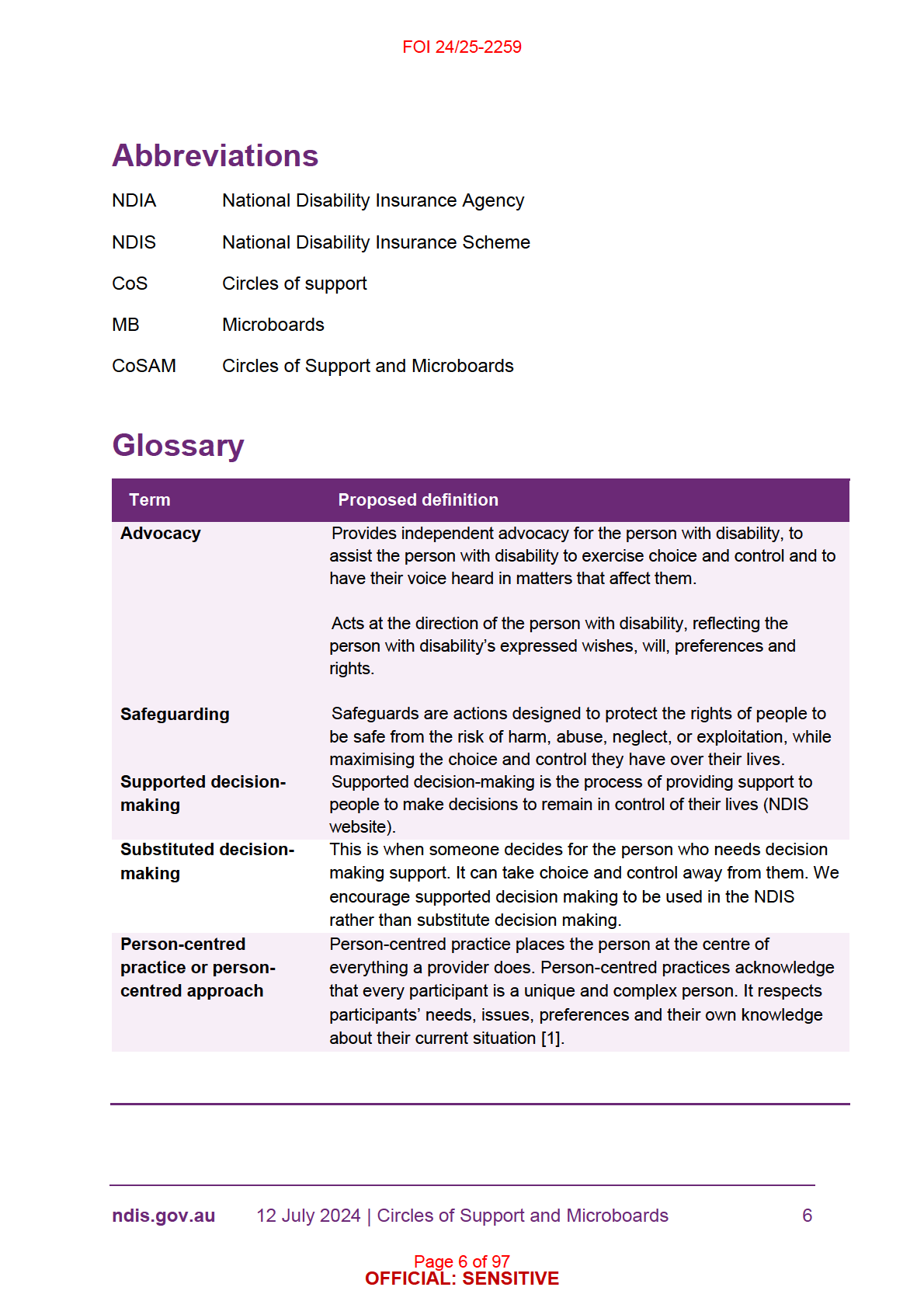

Abbreviations

6

Glossary

6

1. Executive Summary

7

2. Background and NDIS context

9

3. What we did

10

3.1

Data collection

11

4. Key findings

11

4.1

Circles of Support

11

4.1.1

Aims of CoS.

12

4.1.2

The target population for CoS.

12

4.1.3

Key components of a CoS.

13

4.1.4

How providers support the formation of a CoS.

14

4.1.5

Time required to set-up a CoS.

14

4.1.6

Costs for CoS

14

4.1.7

How CoS providers function and who runs them.

15

4.2

Microboards

15

4.2.1

Aim of Microboards

16

4.2.2

Target population of Microboards

16

4.2.3

Key components of Microboards

17

4.2.4

How providers support the formation of Microboards.

17

4.2.5

Legal responsibilities

18

4.2.6

Time required to set up Microboards.

18

4.2.7

Costs for Microboards.

19

4.2.8

Hiring employees.

19

ndis.gov.au

12 July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

2

Page 2 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

4.2.9

How Microboard providers function and who runs them.

20

4.3

Findings relevant to both Circles of Support and Microboards

20

4.3.1

How CoSAM ensure they provide supported decision-making

21

4.3.2

Challenge to provide supported decision-making

23

4.3.3

Working with third parties.

24

4.3.4

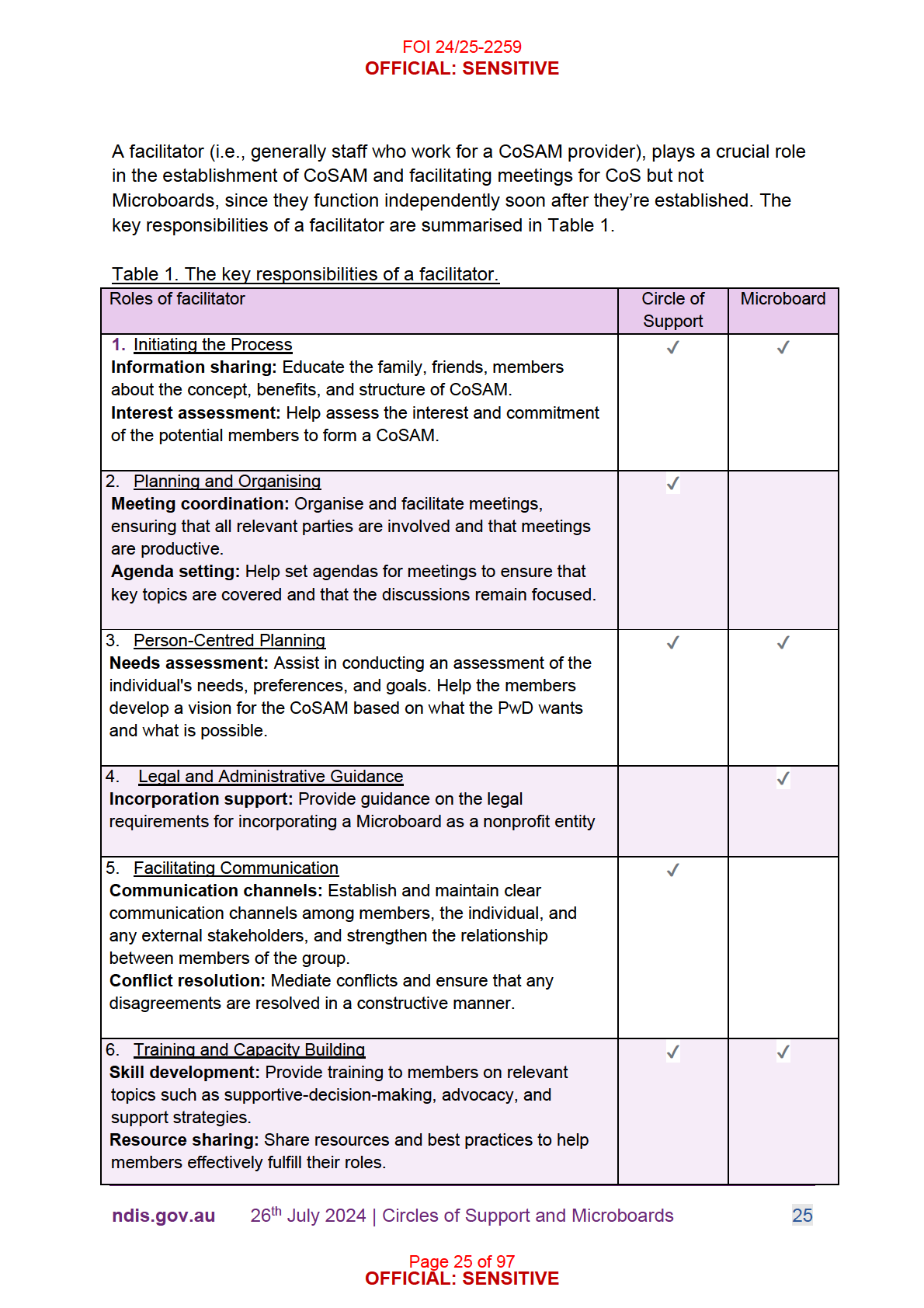

Facilitation for CoSAM.

24

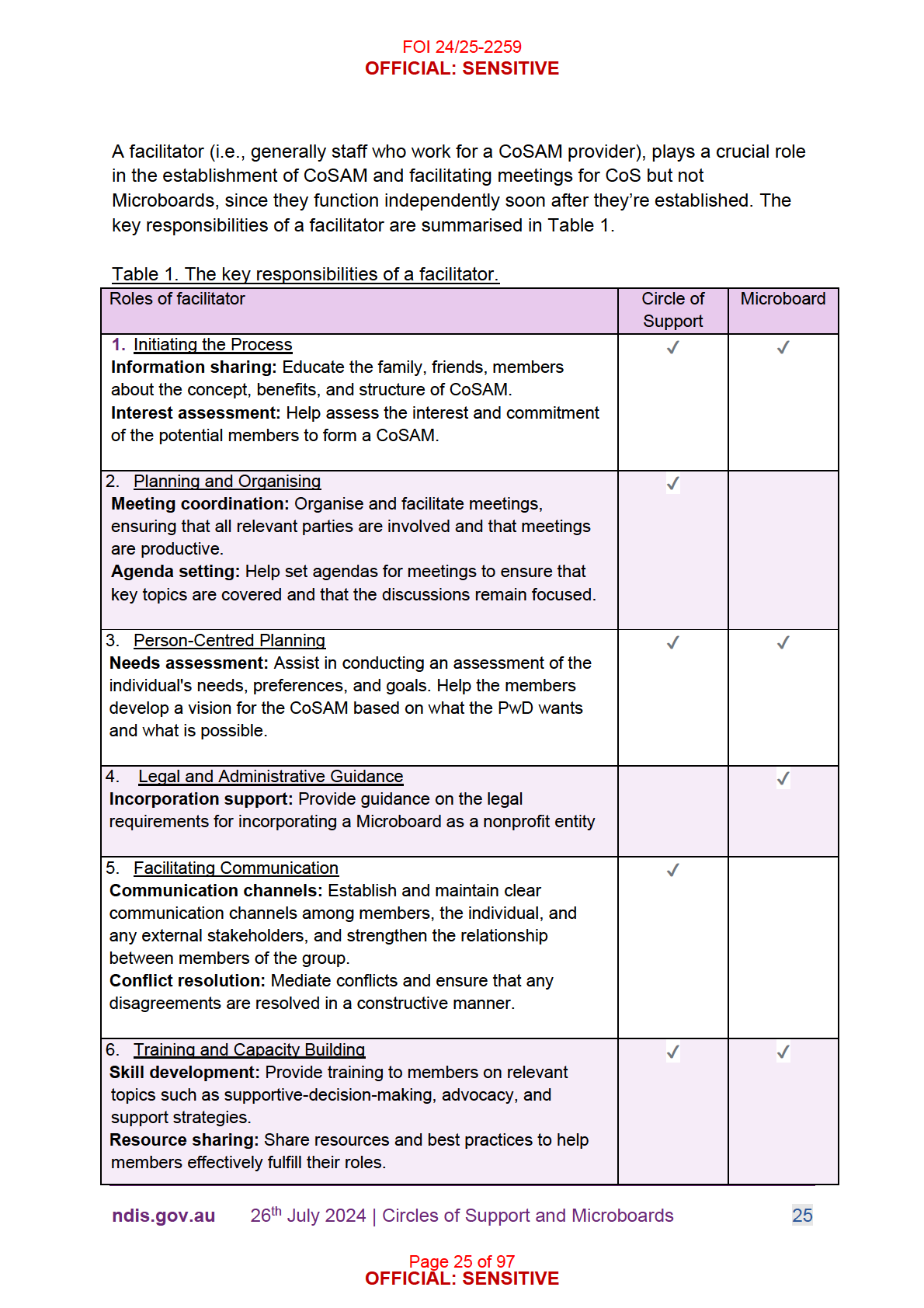

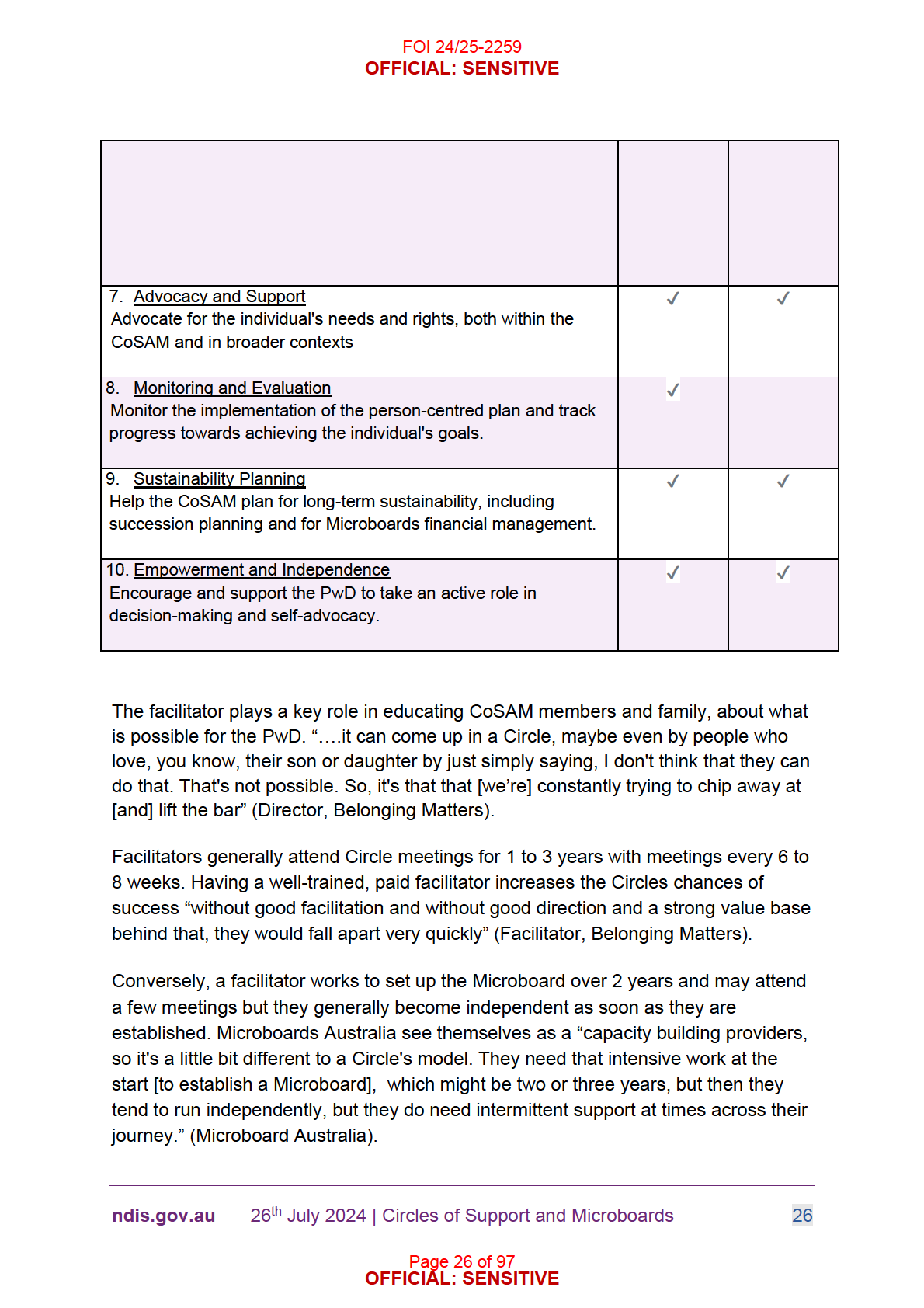

1. Initiating the Process

25

1.1.1

Cost of facilitators

27

1.1.2

Safeguarding provided by CoSAM.

27

1.1.3

Sustainability.

28

1.1.4

Considerations for CALD and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

people 29

1.1.5

Challenges experienced by CoSAM providers.

30

2. Microboards versus Circles of support

32

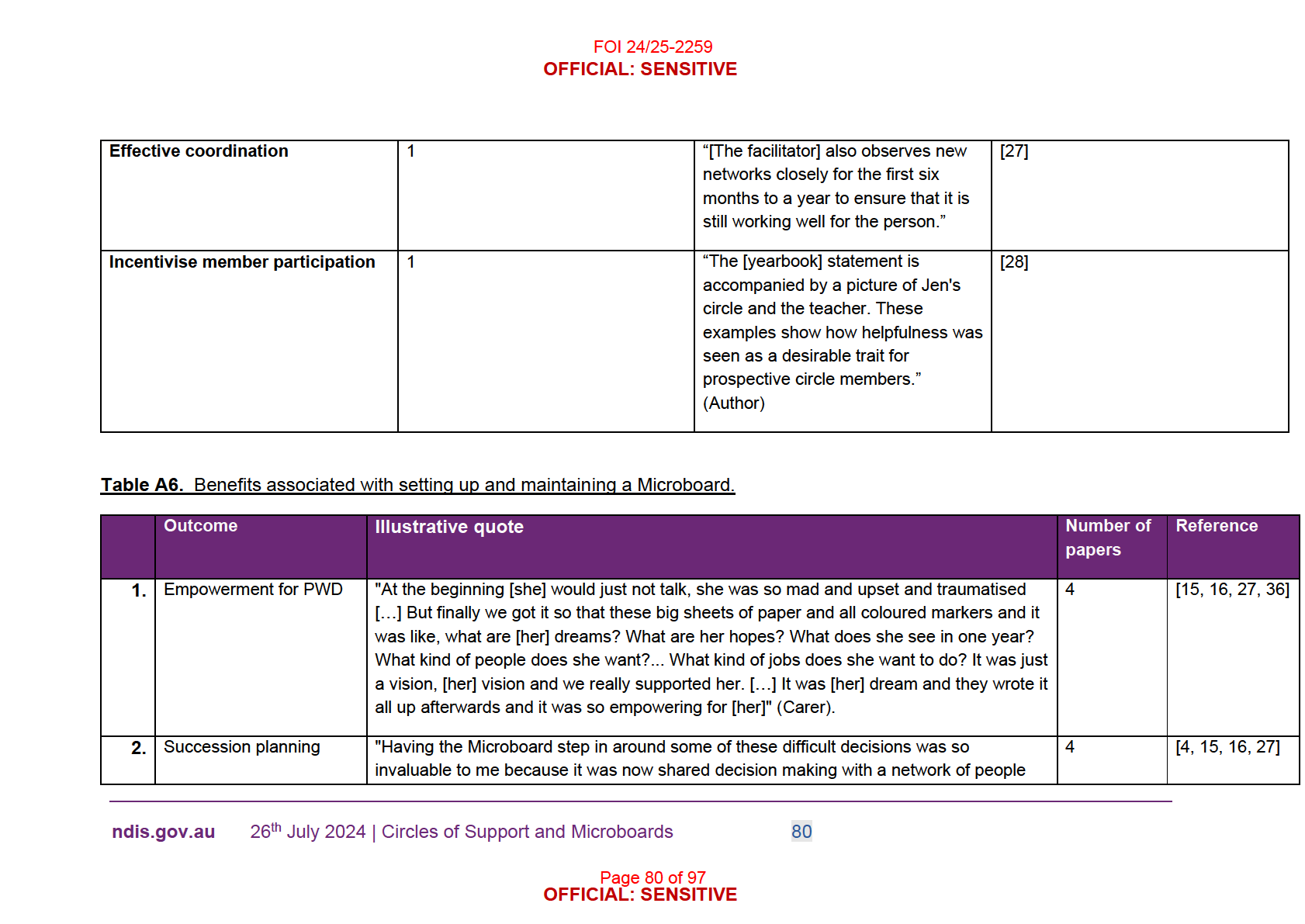

3. Outcomes for Circles of support and Microboards

33

3.1

Benefits of Circles of Support

33

Supported decision-making.

33

Oversight.

34

Support and respect.

34

3.2

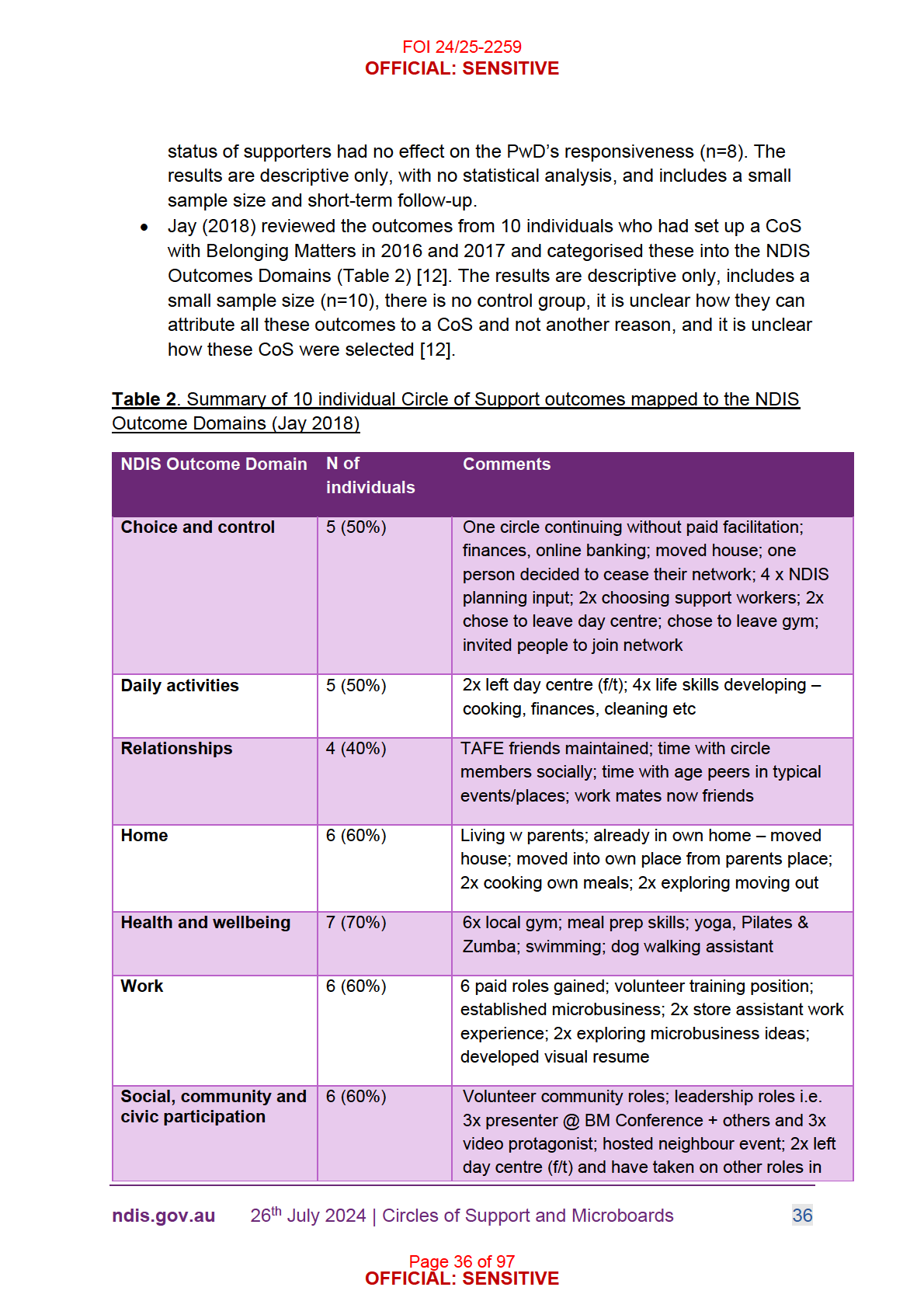

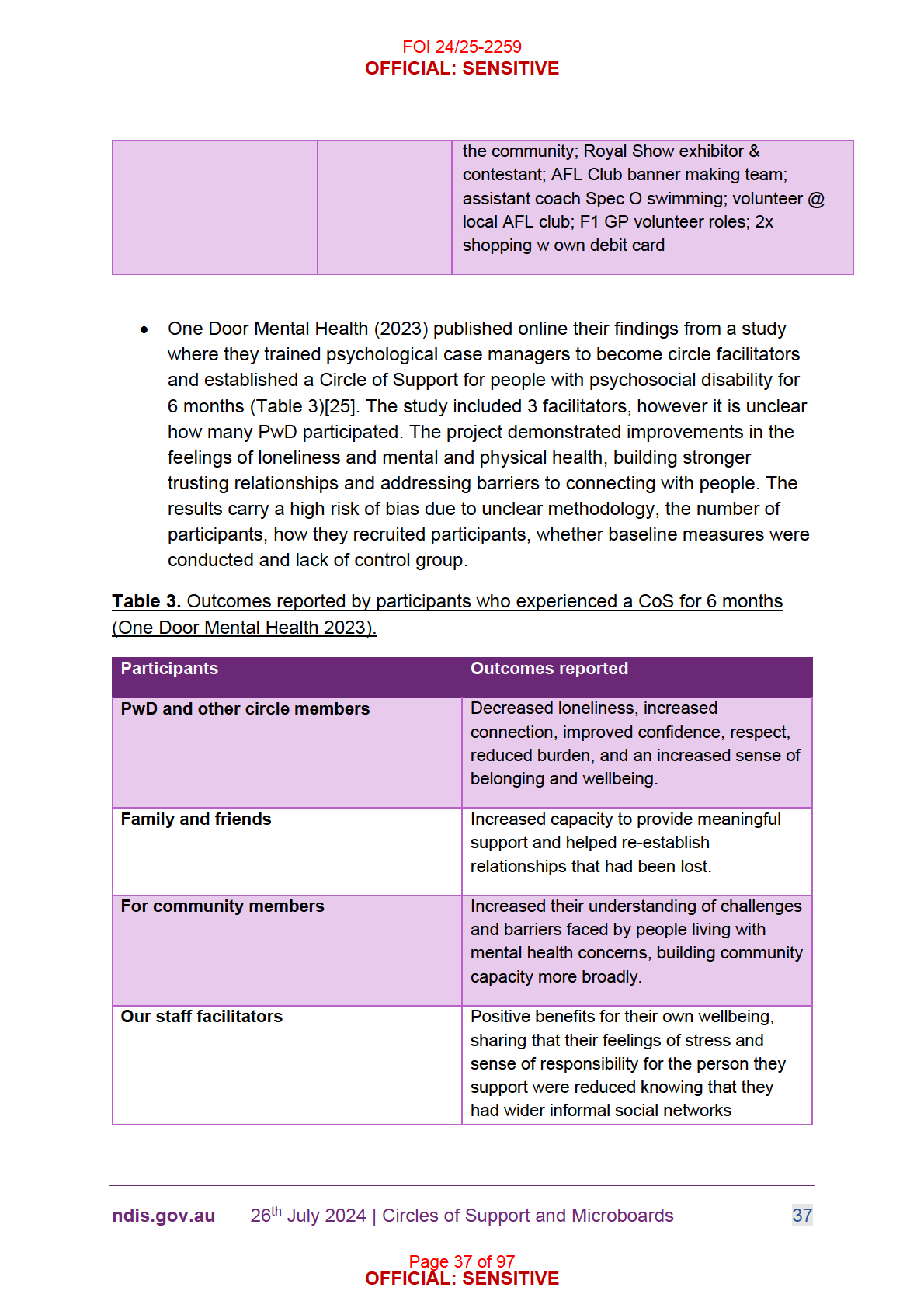

Quantitative data

35

3.3

Risks of Circles of Support

38

Substituted decision-making and who is responsible.

38

PwD may not want a CoS.

38

Lack of commitment from members of CoS

38

3.4

Benefits of Microboards

39

Supported decision-making

39

Benefit people of all ages

39

Additional support

39

Safeguarding

40

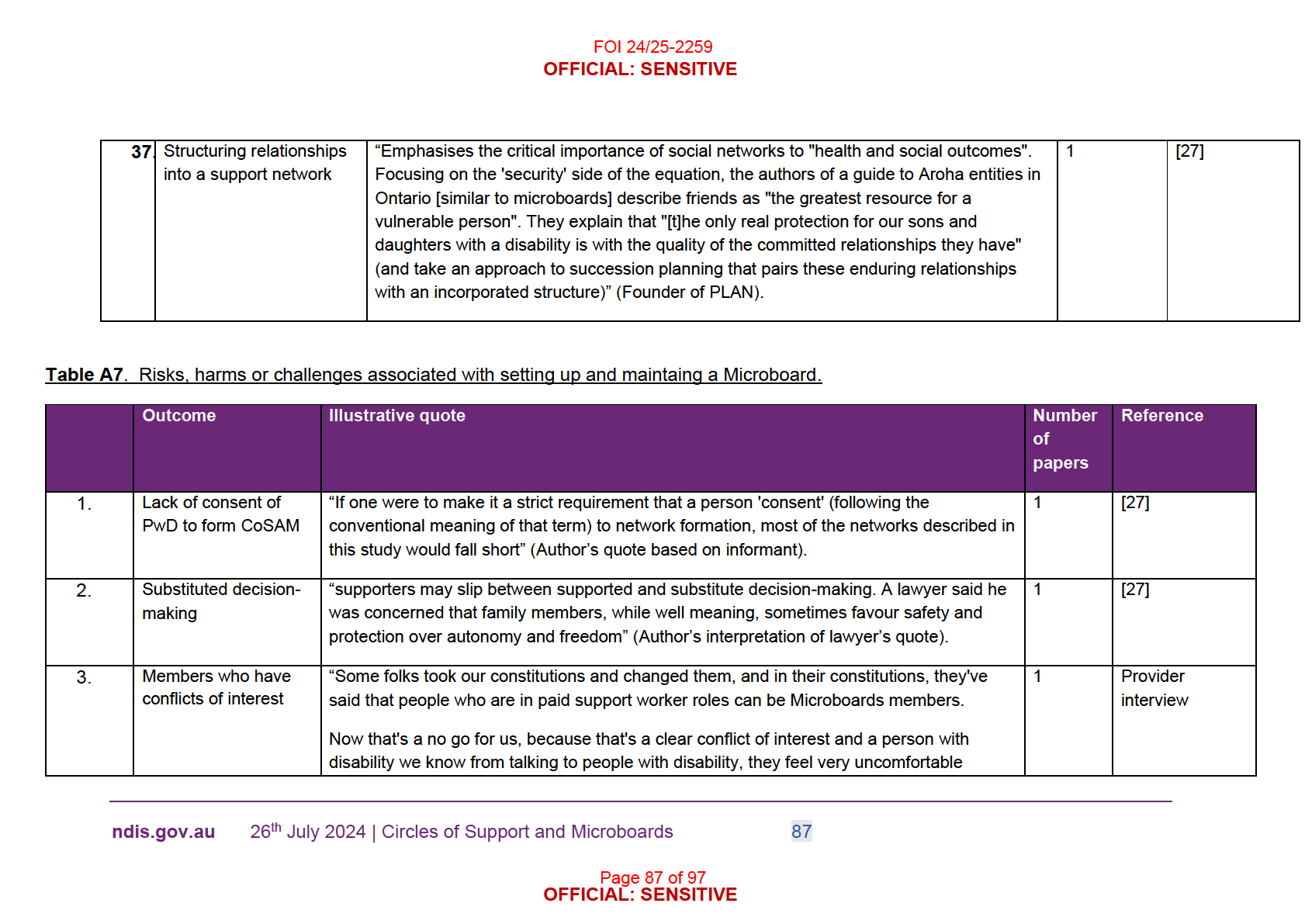

3.5

Risks of Microboards

40

Substituted decision-making

40

ndis.gov.au

12 July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

3

Page 3 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

PwD not wanting a Microboard or able to choose members

41

Members exploit their position

41

Legal ambiguity

41

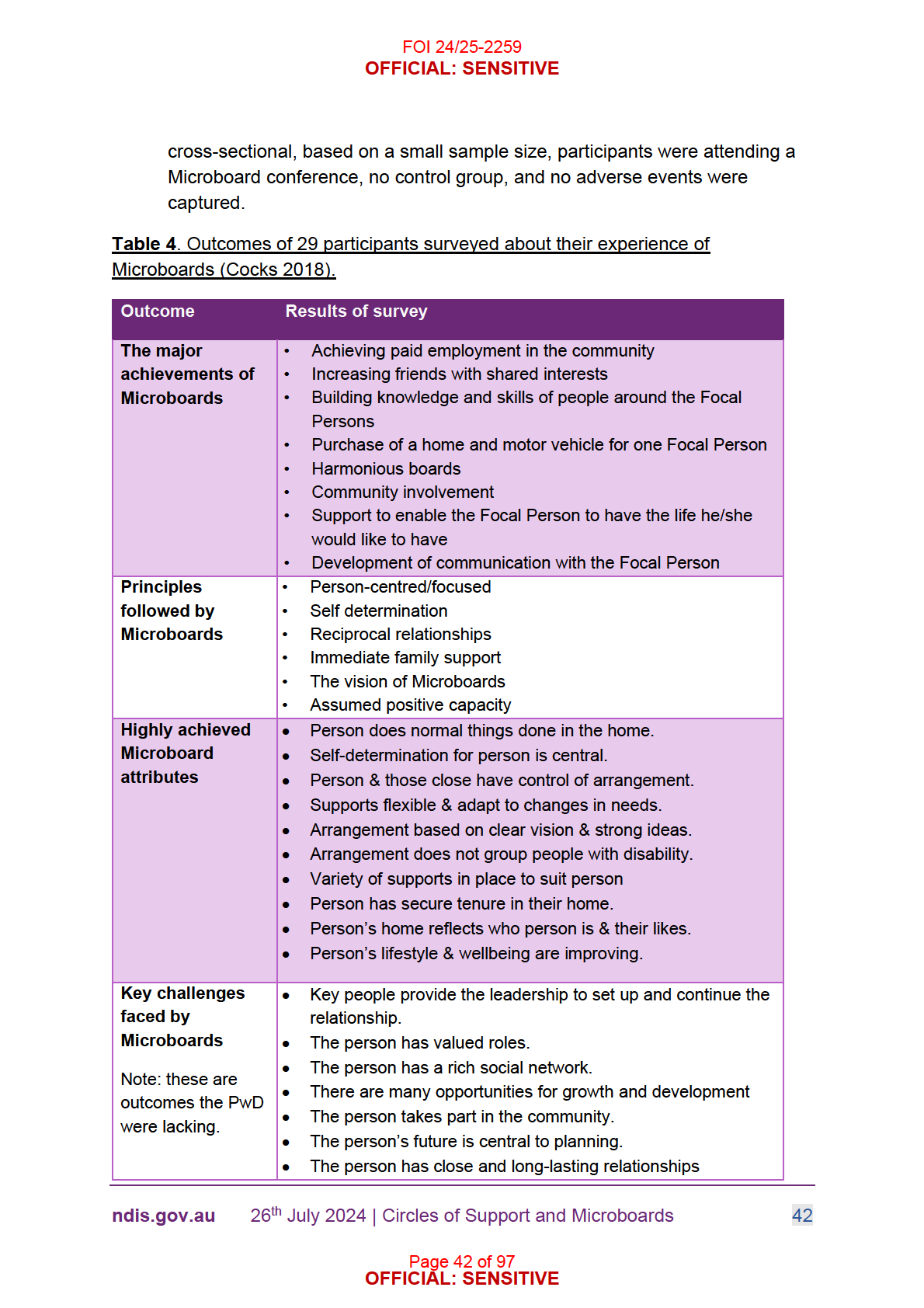

3.6

Quantitative findings on Microboards

41

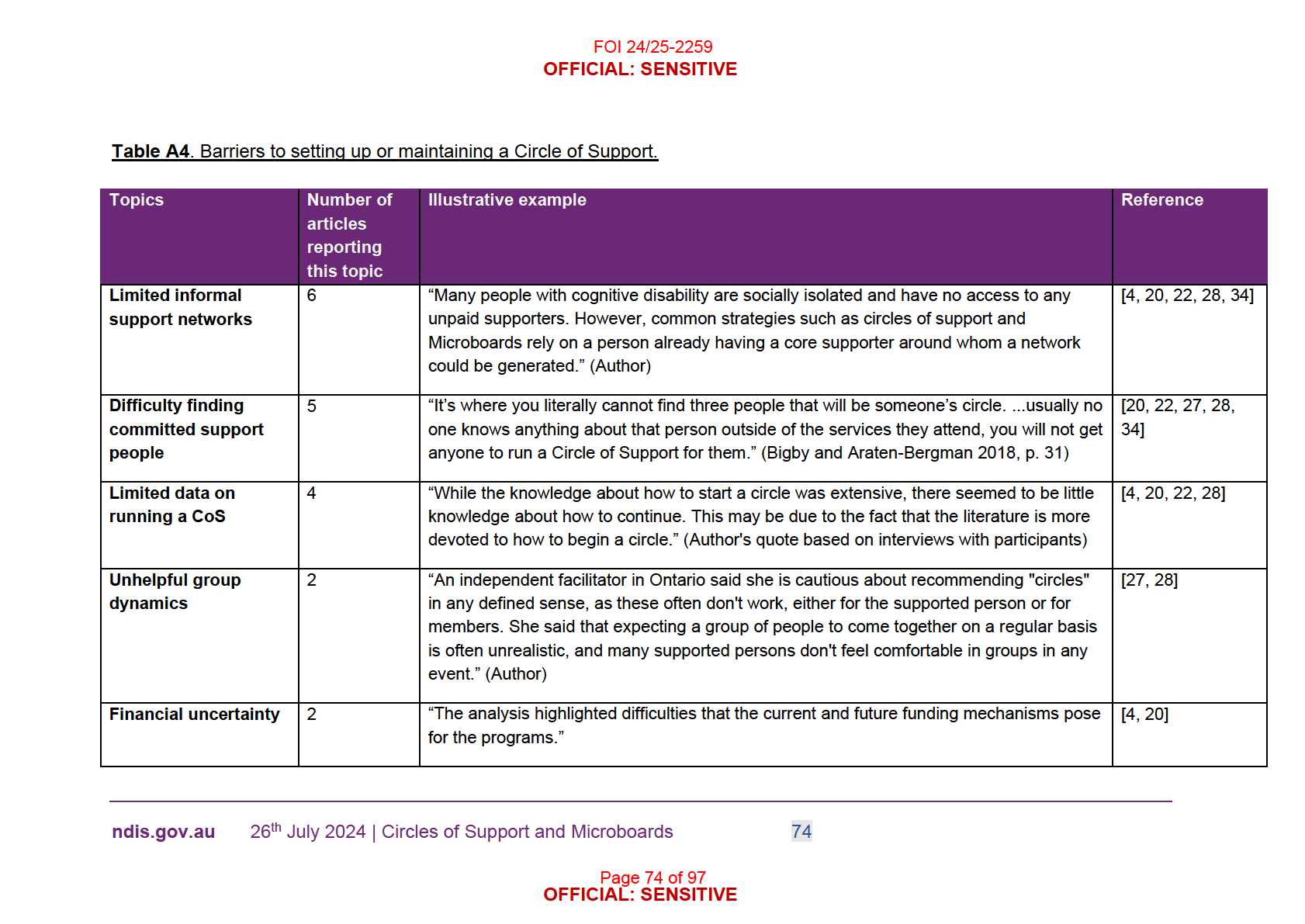

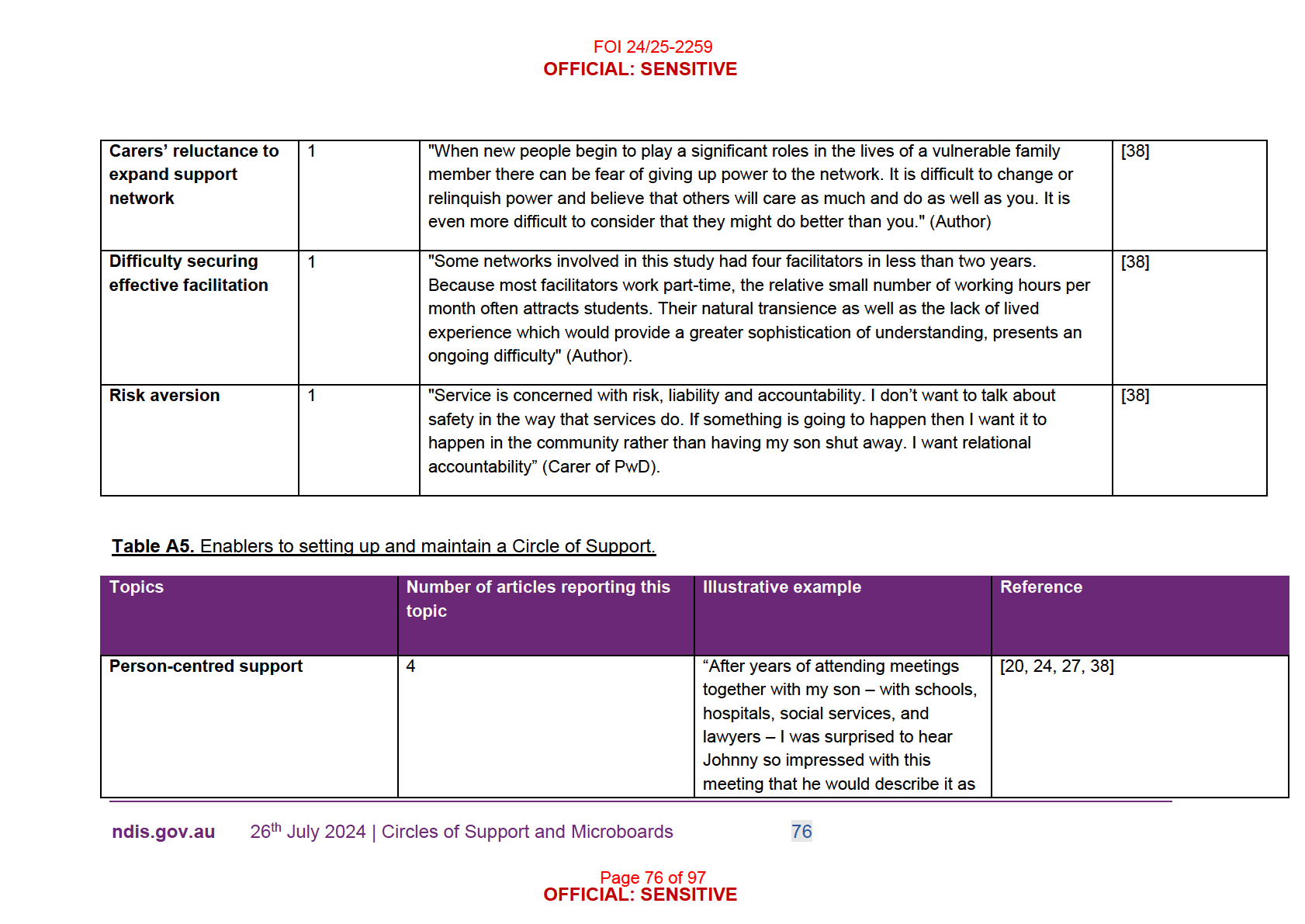

4. Barriers and enablers to setting up and maintaining Circles of support and

Microboards.

43

4.1

Barriers for Circles of Support

43

4.2

Enablers for Circles of Support

44

4.3

Barriers for Microboards

44

4.4

Enablers for Microboards

44

5. Summary of key findings

45

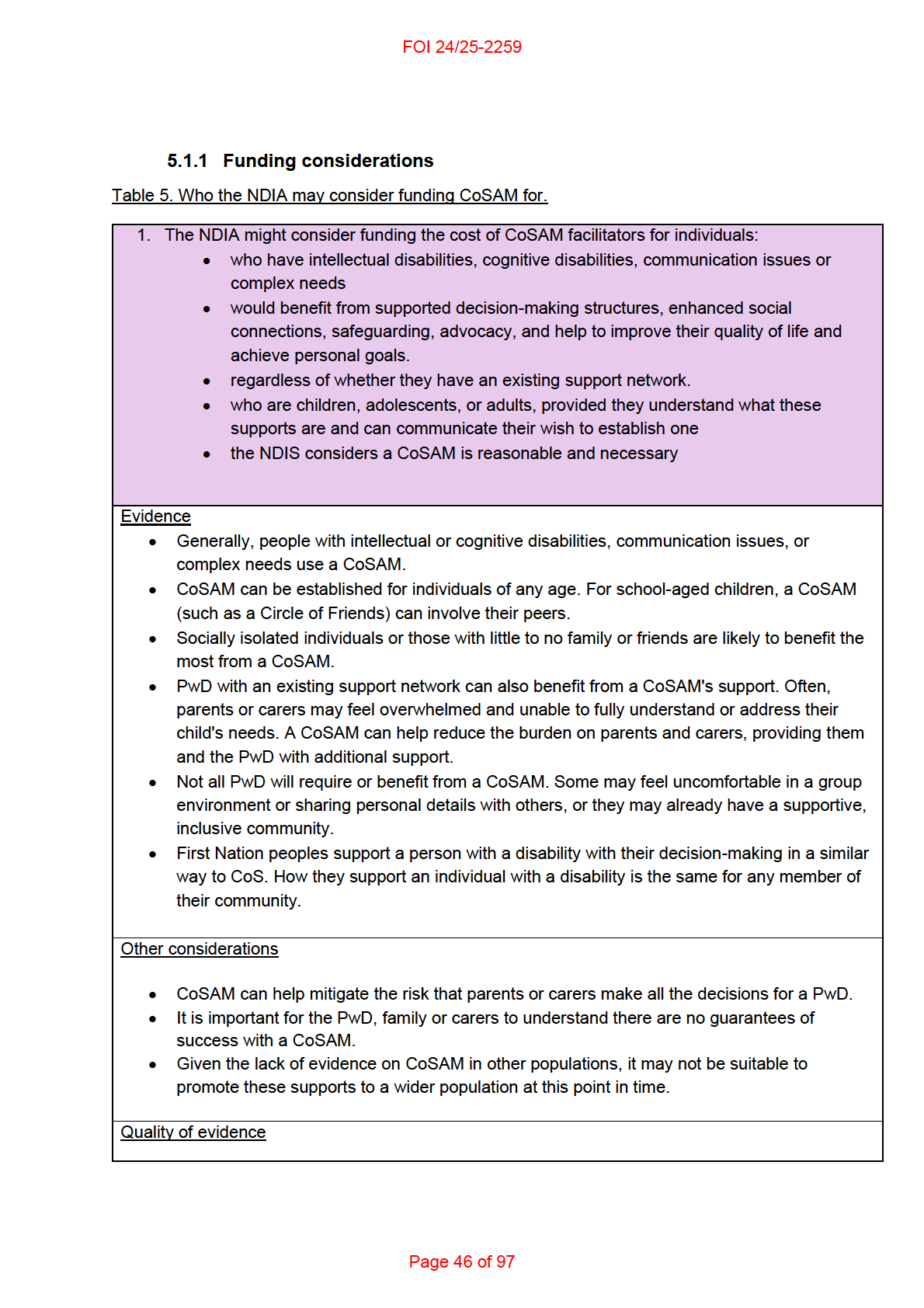

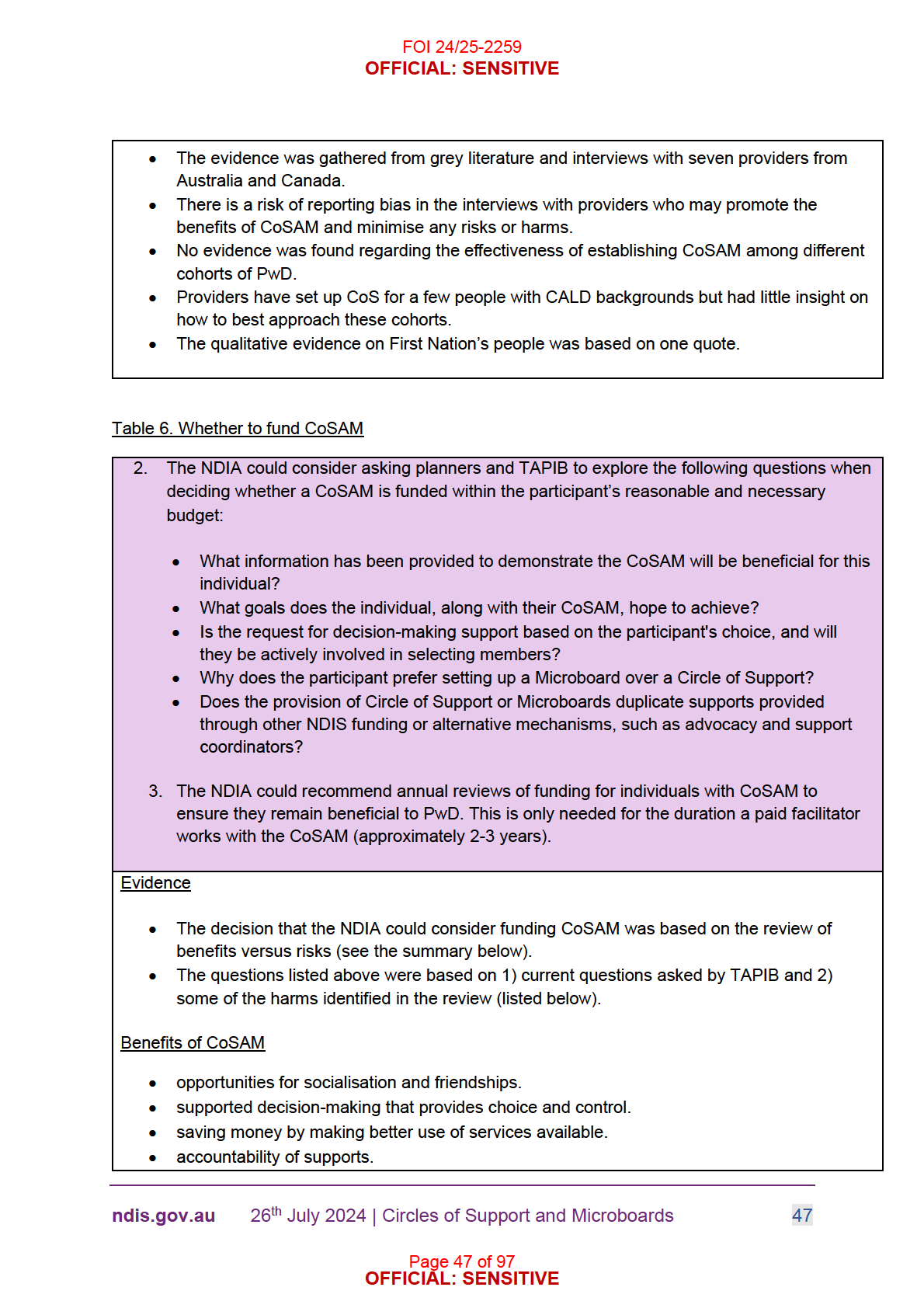

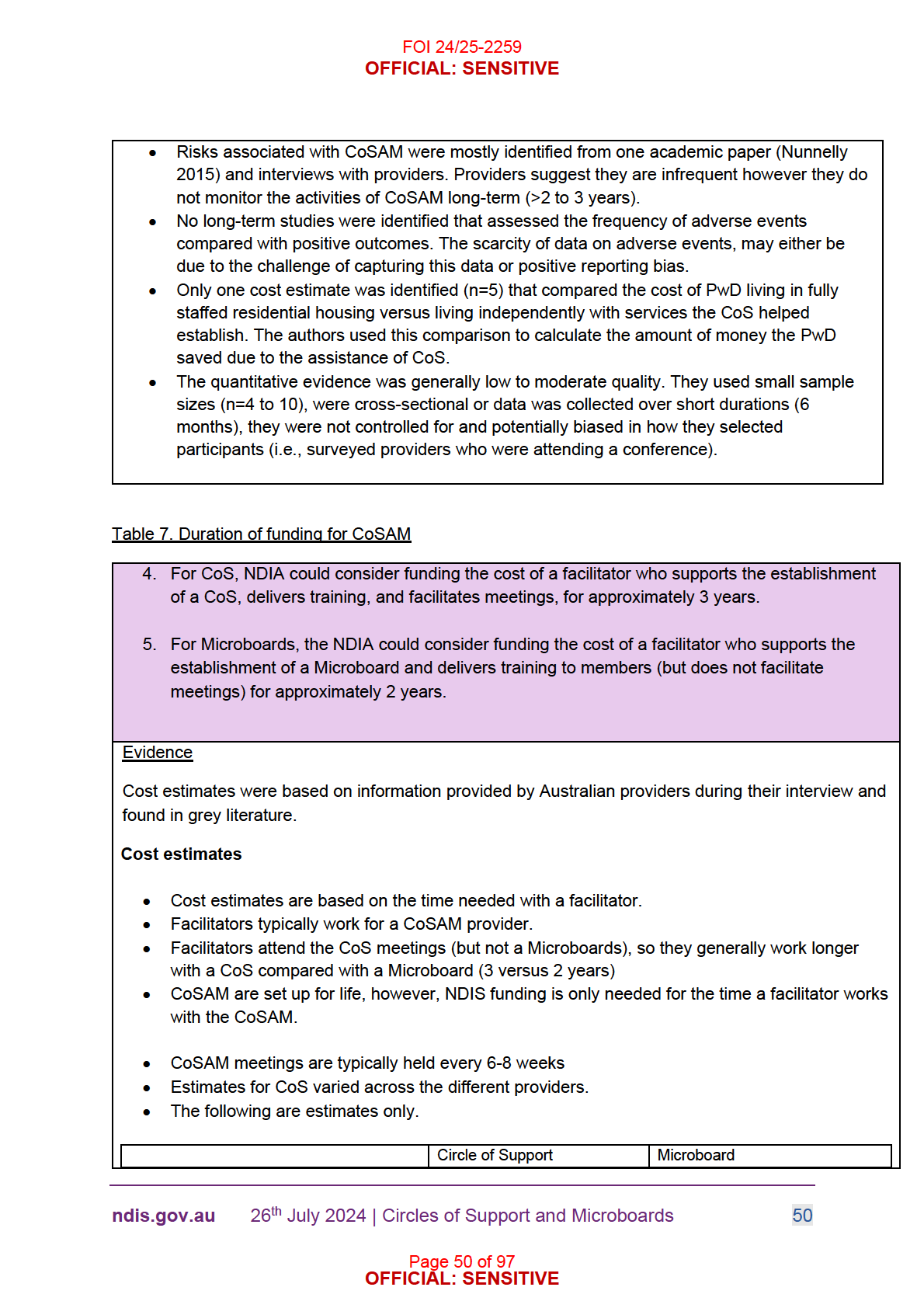

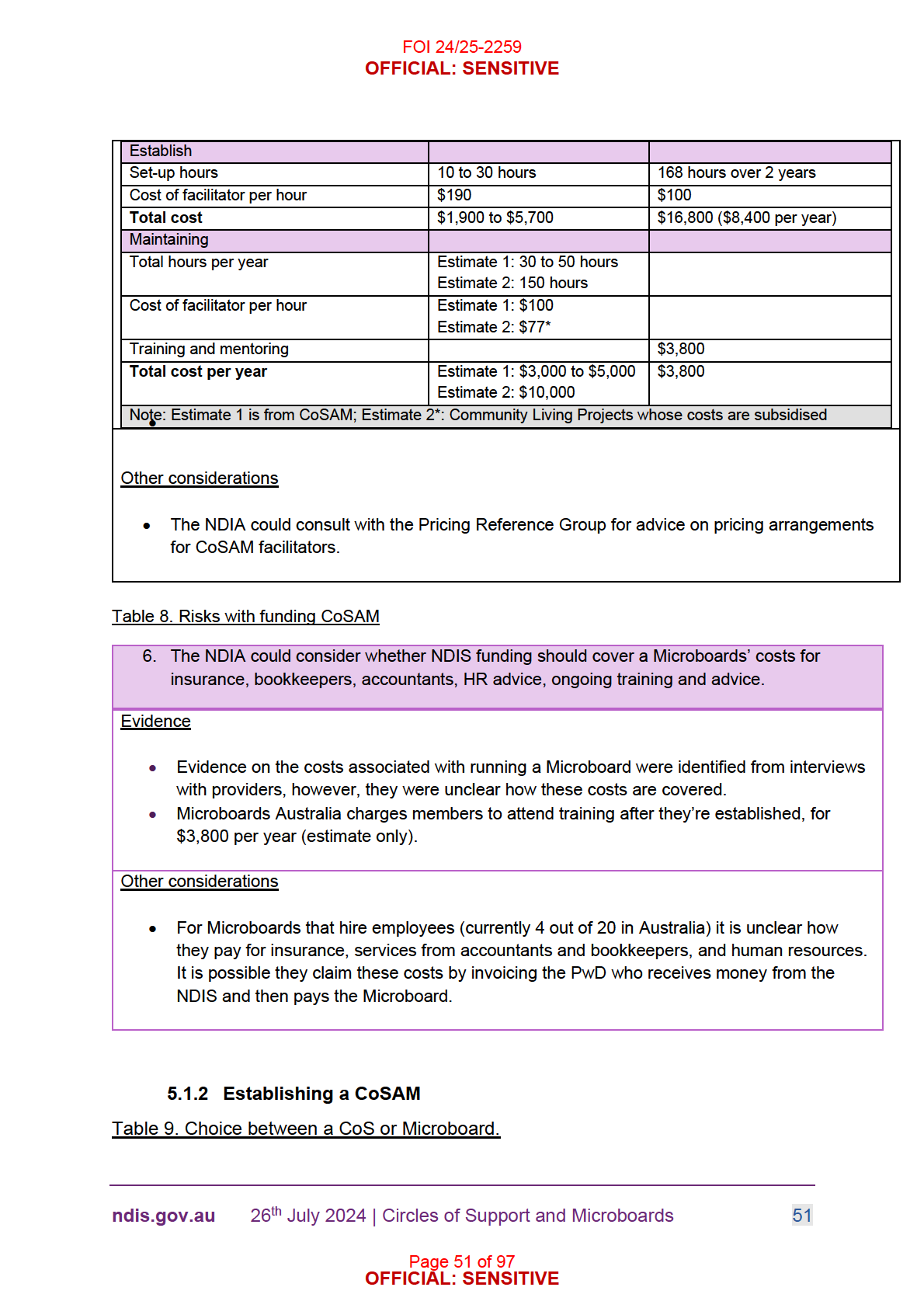

5.1.1

Funding considerations

46

5.1.2

Establishing a CoSAM

51

5.1.3

Implementing CoSAM

53

6. Limitations of this evidence

58

7. Strength of evidence

58

8. Research gaps

59

9. Next steps

59

10. Appendix

61

11. References

95

National Disability Insurance Agency

97

ndis.gov.au

12 July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

4

Page 4 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

Disclaimer

The NDIA accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of any material

contained in this report. Further, the National Disability Insurance Agency disclaims

all liability to any person in respect of anything, and of the consequences of anything,

done or not done by any such person in reliance, whether wholly or partly, upon any

information presented in this report.

Views and recommendations of third parties in this report, do not necessarily reflect

the views of the NDIA, or indicate a commitment to a particular course of action.

However, this report may inform the implementation of home and living policies in

the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

Acknowledgements

The NDIA acknowledge the Traditional Owners and Custodians throughout Australia

and their continuing connection to the many lands, seas, and communities. The

NDIA pay respect to Elders past and present and extends this to any Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander people who may be reading this Report.

Suggested Citation

National Disability Insurance Agency 2024. An Evidence Snapshot of Circles of

Support and Microboards. Prepared by Evidence and Practice Leadership Branch.

ndis.gov.au

12 July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

5

Page 5 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

1. Executive Summary

This report provides an in-depth exploration of Circles of Support (CoS) and

Microboards (CoSAM) that aim to provide supported decision-making, promote

social inclusion and safeguarding to people with disabilities (PwD). Generally the

goals of the CoSAM are aspirational, such as empowering the individual to have

control over their life and to maximise their independence. Members include a

committed group of trusted and known individuals such as family members, friends,

peers, mentors, and professionals.

Microboards are similar to a Circle except they become a small, non-profit

organisation that is governed by members who become a board of directors.

Microboards may also take on the responsibility of employing support workers for the

PwD, purchasing property and opening bank accounts.

Key Findings:

Benefits: CoSAM facilitate supported-decision making, socialisation, advocacy, and

personalised support, enhancing quality of life for PwD. They provide safeguards

against abuse, promote self-determination, and offer continuity of support beyond

family involvement.

Risks: Challenges for CoSAM may include unintended impacts such as: unactioned

ideas or activities, financial abuse, substituted decision-making, lack of consent to

establish a CoSAM by PwD, employee complaints, and unclear legal responsibilities

for Microboard members.

Barriers: time commitment, NDIS funding, finding committed members,

administrative complexities, funding to establish and maintain CoSAM and

ambiguities regarding legal responsibilities.

Enablers: effective facilitation, a person-centred approach and collaborative efforts

among members.

Future Directions: Continued research and evaluation, including well-designed

evaluation studies with validated measures, cost-effectiveness analysis, and long-

term data (>2 years), are needed.

Limitations: Findings are constrained by low quality quantitative evidence, lack of

long-term data, potential reporting bias from providers, small sample sizes, and little

consideration of First Nations people and people with CALD backgrounds.

Page 7 of 97

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

NDIS Policy and Review:

The NDIS policy on supported decision-making, recognises that “all participants,

including people with profound intellectual and multiple disability, have the right to

support to make or direct decisions that impact their lives”. And that “decision making

support may come from a person, or several people, in formal or informal ways that

include: Microboards; Circles of support; Network Facilitators; Decision Coaches”.

The NDIS review (2023) recommends the “National Disability Insurance Agency

should include an assessment of participants’ need for independent decision-making

support as part of budget setting and ensure participants can use their NDIS budgets

to access independent decision-making supports”.

Challenges and Considerations:

Providers who assist with the establishment of CoSAM emphasise that CoSAM go

beyond supported decision-making strategies; they offer a multitude of benefits,

including enabling PwD to lead enriched lives, facilitate meaningful employment,

maximise their independence, providing safeguarding and advocacy, establish

crucial social connections and assist with succession planning for when family

supporters age and die. Providers believe these outcomes are often unachievable

without the structured, committed support of a trusted group dedicated to assisting

and empowering the PwD. Whilst this finding is supported by interviews from PwD

and their carers, there are no studies that compare outcomes in people who have a

CoSAM compared with normal care with support from a support coordinator.

Establishing a CoSAM is not without risks. Providers and the NDIA need to ensure

CoSAM do not provide substituted decision-making or Microboards misuse NDIS

funds when paying for support-workers, tax advice and insurance. While paid

external facilitators can help provide oversight, they typically work with a CoSAM for

only 1-3 years, thus it is unclear who will take on this responsibility thereafter.

Funding for CoSAM supports could be deemed reasonable and necessary for

persons with intellectual disability, cognitive disability, communication issues or

complex needs. The choice between a CoS or Microboard is generally made with the

PwD, their family or carer in conjunction with a provider who can explain the pros

and cons of each. Providers are not registered by the NDIA, so The NDIS Quality

and Safeguards Commission may need to consider whether to amend this to

address the inequity of access for these supports for people with an Agency- funded

budget.

Funding for CoSAM is generally needed for 1 to 3 years, depending on whether the

PwD has existing supports and for Circle members, their confidence to function

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

8

Page 8 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

independently of a paid facilitator. Funding covers the cost of facilitators who help

establish CoS (average $3,800) and Microboards ($8,400 per year), and facilitate

meetings for CoS, for approximately 1 to 3 years ($4,000 to $10,000 per year).

These pricing arrangements would need to be considered by the Pricing Reference

Group.

Providers are not registered by the NDIA, so The NDIS Quality and Safeguards

Commission may need to consider whether to amend this to address the inequity of

access for CoSAM for people with an Agency-funded budget. Registering the

providers will also add more oversight to the industry, since they will be subject to

quality-standard audits.

The NDIA’s policy position may be best decided with the support of an advisory

panel who can deliberate on the evidence to produce evidence-based advice and

recommendations. This will create a structured and transparent decision-making

process, building trust and credibility in the decisions and recommendations,

especially where uncertainty exists.

2. Background and NDIS context

Supported decision-making is the concept that individuals with mental or intellectual

disabilities should have the ability to make decisions about their own lives with the

assistance of a supportive team. This approach promotes self-determination and

independence, contrasting with the guardianship model, where decisions are made

on behalf of the person [2].

According to the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC), "all persons who

require support in decision-making must be provided with access to the support

necessary for them to make, communicate and participate in decisions that affect

their lives” [3]. The Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect, and

Exploitation of People with Disability (The Commission) has built on the ALRC's

findings, underscoring the importance of supported decision-making to ensure that

people with disabilities can make decisions for themselves with dignity and

autonomy [4].

From the NDIS perspective, the NDIS Act and NDIS Supported Decision-Making

Policy (2023) stipulates that “NDIS funding for supports such as network facilitation

and Microboards may be available if it is reasonable and necessary” [5].

Furthermore, the NDIS Review (2023) proposed that “participants should be allowed

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

9

Page 9 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

to use their NDIS budgets to establish decision-making support networks (such as

circles of support)” (Action 5.3) [6].

Circles of Support and Microboards (CoSAM) are designed to provide supported

decision-making to people with disability, to help them have live an enriched and

fulfilled life that includes social activities, choice and control over their decisions,

maximise their independence, good quality supports and fulfilling employment.

CoSAM typically consist of trusted and known family members, friends, peers,

mentors, and professionals.

CoSAM are used by people who have intellectual disabilities, cognitive disabilities,

communication issues or complex needs. These individuals can benefit greatly from

the additional support since many are socially isolated with few others involved in

their lives [7]. Providers of CoSAM will help identify potential members and may help

build new relationships if needed for those who do not have a strong social network.

Their social networks are small and dense, often comprised only of family members,

peers with intellectual disabilities and paid staff. Yet people with intellectual

disabilities report that neither families nor service providers understand the

significance of informal relationships and fail to provide the practical support

necessary to form and maintain such relationships. Various formal strategies to build

and maintain informal social networks for people with intellectual disabilities are

reported in the academic and grey literature.

In August 2023, a review submitted to the NDIS review committee by members of

the CoSAM Community of Practice in Australia, that includes Inclusion Melbourne,

Deakin University and Microboards Australia, described how CoSAM are funded, are

beneficial , can measure progress; can help access supports and provide

safeguarding [8]. Recommendations from the review focused on the need for NDIS

guidance on CoSAM; to set up a CoSAM advisory group; to acknowledge the

benefits of CoSAM and to fund them.

In 2024, the NDIA has received several requests for funding of CoSAM and is

currently developing policy and operational guidance for front line decision-making.

This evidence summary was undertaken to provide an updated review of the

available evidence (both research and practice -based) to help inform the NDIA’s

position on who they are best suited for, how they’re implemented, their benefits,

risks, barriers and enablers.

3. What we did

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

10

Page 10 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

This evidence summary addressed the following questions on CoS and Microboards:

1) What is the current state of evidence for CoS and Microboards for supported

decision-making?

2) What are the benefits and risks associated with these strategies for people

with disability, their family and/or carers?

3) What design features and implementation factors should be considered when

setting up and/or maintaining CoS and Microboards?

4) What are the enablers and barriers to setting up and ongoing implementation

of CoS and Microboards?

5) How can CoSAM providers build community connections and informal

supports for people who are isolated or have minimal existing supports?

This is the first phase of work, being led by the Research and Evaluation Branch, to

help inform the NDIA’s position on funding CoSAM.

3.1 Data collection

We conducted a grey literature search using Google and Google Scholar. We also

undertook a search of ERIC, PRO-QUEST, Trove and Analysis Policy Observatory.

The peer reviewed literature search included primary research and systematic

reviews. PsycINFO, Medline, CINAHL and EMBASE databases were searched..

One reviewer (LS) conducted semi-structured interviews

with seven

representatives

of CoSAM providers in Australia and Canada via on-line video conferencing

software, including: Belonging Matters, Life Assist, Imagine More, Community Living

Project, Microboard Australia, Vella Microboards Canada and Microboards Canada.

A meeting with NDIS trainee planners was also conducted to explore how they would

consider a request for CoSAM funding.

4. Key findings

We screened 551 academic literature records and 10 met the eligibility criteria. An

additional 14 reports were identified from the grey-literature that included

government reports, organisation reports and theses (Supplementary Material S1).

4.1 Circles of Support

This section of the evidence summary compares the key features of four Australian

providers that support the creation of Circles of Support (CoS): Belonging Matters,

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

11

Page 11 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

Life Assist, Imagine More, and Community Living Project. Information was gathered

from the providers' websites, published reports, and interviews with representatives

from Belonging Matters, Inclusion Melbourne, Imagine More, and Community Living

Project.

4.1.1 Aims of CoS.

The aims of CoS are to:

1.

Empower the PwD to live a fulfilling life: enable PwD to have the same

opportunities in life as other people in the community, and to ensure their lives

are fulfilling, unique, socially inclusive, and empowering

2.

Provide structure to existing supports: enable existing informal supports to

help the individual and their family achieve their goals by providing structure

and formal processes.

3.

Long-term support: to co-design a succession plan for when family are no

longer able to and to provide a sustainable network of support over the

individual’s life time

4.

Help PwD form deeper relationships: to help the PwD expand their contacts,

associations and connections.

5.

Provide opportunities for social activities: CoS can help provide social

supports and social opportunities for the PwD.

Interviews with providers revealed that the goals of CoS should be aspirational,

helping individuals with disabilities envision what is possible in their lives (Belonging

Matters, Imagine More). The purpose of a CoS is not to default to ‘easy’ options like

segregated employment or group home living, but to assist individuals in achieving a

full, meaningful, and inclusive life. This includes securing open-market employment,

pursuing interests and hobbies, or living independently (Belonging Matters). For

example, if a PwD prefers to stay in segregated employment because their friends

are there, the CoS should help them understand their options and explore what

fulfilling employment could look like (Belonging Matters).

“People with intellectual disability are so vulnerable to services and the impact of

systems just taking over their life and saying, you know what this would be so much

easier if you went to a day program and you lived in a group home. You know? So

really the circle with a mechanism to safeguard people's vision but also bring other

people into their life” (Director, Belonging Matters).

4.1.2 The target population for CoS.

CoS are designed to assist people with disabilities, particularly those with intellectual

disabilities and autism. Some providers, like Life Assist, have eligibility criteria for

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

12

Page 12 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

setting up a CoS, working only with individuals who already have existing networks.

Others, such as Belonging Matters and Imagine More, believe that everyone has a

network that can be discovered and engaged with time and effort. For individuals

without a network, facilitators at the Community Living Project enlist other support

workers to help establish one.

Inclusion Melbourne expresses concerns about excluding those without existing

networks “it means that those [who] are less privileged … are more disenfranchised,

would struggle” (Head of Policy, Research, and Advocacy, Inclusion Melbourne).

Most PwD who are creating a CoS will need some level of assistance with their

decision-making. However, providers like Belonging Matters and Imagine More do

not assess this need or use it as an eligibility criterion. Belonging Matters requires

that PwD have “a vision for a good life. They need to want it. If they don't want that,

then there are a million other providers that can help them with segregated care, so

we just leave that to other providers to do” (Facilitator, Belonging Matters).

CoS are also crucial for individuals whose parents are elderly and may soon pass

away, as they ensure continuity of care and support, “You know that there are a

group of people around the person who are unpaid to safeguard them when families

are no longer here” (Facilitator, Belonging Matters).

CoS are promoted for young people, especially when they’re attending school. CoS

may involve recruiting school friends to join, potentially holding meetings at school to

facilitate support during school hours and provide opportunities for social activities

for the PwD.

4.1.3 Key components of a CoS.

• Circles of Support include members familiar with the PwD, such as family,

school friends, neighbours, and service providers.

• The PwD actively participates in selecting CoS members.

• Meetings are held regularly, typically every six weeks, often at the PwD’s

home.

• Facilitators are crucial for CoS success:

• They ensure the PwD’s goals are aspirational.

• They involve the PwD in decision-making.

• They encourage active participation from members inside and outside of

meetings.

• Facilitators should not be family members to maintain neutrality.

• The PwD may need time to feel comfortable in meetings.

• CoS collaboratively works toward common goals for the PwD.

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

13

Page 13 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

• Membership in CoS is initiated and meetings are planned by the members

themselves.

4.1.4 How providers support the formation of a CoS.

Some providers spend several months working closely with families and PwD before

inviting members to join a CoS. They assess the PwD's needs and social network to

determine if a CoS is appropriate (United Care Queensland, Belonging Matters). Not

everyone may find CoS suitable; some PwD may prefer individual mentoring or

joining peer support groups (Belonging Matters). Once a decision is made to

establish a CoS, providers evaluate the existing network and assist in inviting

members. Belonging Matters suggests interested parties submit an expression of

interest and involve the PwD when selecting members to join.

4.1.5 Time required to set-up a CoS.

The time and effort needed to establish a CoS vary depending on whether the

individual has an established support network (Belonging Matters, Inclusion

Melbourne, Life Assist).

On average, facilitators invest 15 hours (10 to 20 hours) to set up the CoS, then 4 to

8 hours per meeting (usually every 6 to 8 weeks) for the first 3 years (Inclusion

Melbourne). Meeting times include preparation time and follow-up tasks. After 3

years, paid facilitation hours are reduced with the goal of having CoS running

independently.

Imagine More do not limit their time since they provide free advice and support (but

do not provide facilitation). Belonging Matters describes the need to consult with

families and the PwD over several months before invites to join the CoS are sent out.

Inclusion Melbourne believes it may take a year before a circle may achieve anything

significant, so outcomes shouldn’t be assessed until then: “the first year is about

forming those natural consolidating national networks. Second year is about a lot of

the goal setting and connection and trying new things. It's not fair to lean on a circle

in the first couple of years…. but by year three it's quite fair for a funder to lean on

that circle for outcomes and outputs” (Head of policy and research, Inclusion

Melbourne).

4.1.6 Costs for CoS

The cost of establishing a CoS depends on the hours worked by the facilitator (Life

Assist, Community Living Project). Generally, a facilitator provides 3 hours of work a

week, so over the year it costs $10,000 for a facilitator. PwD may receive funds to

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

14

Page 14 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

set up a CoS through their NDIS plan, and families may receive financial support

from the government carer support program.

For a provider, the money received to pay for a facilitator covers approximately two

thirds of their running costs. The other third needs to be found elsewhere, such as

grants (Community Living Project).

Imagine More provides free advise and support for setting up a CoS, excluding

facilitation. They receive Independent Living Centre (ILC) funding from the Federal

Government to sustain their staff and operations, with further funding expected to

commence in August (pending confirmation).

4.1.7 How CoS providers function and who runs them.

The not-for-profit CoSAM providers typically operate with 1-9 staff members who

specialise in developing CoS, have expertise in the disability sector, person-centred

planning, and group facilitation. Imagine More has staff with lived experience but

does not employ dedicated facilitators. Some providers, like Belonging Matters,

contract facilitators who they check in with regularly for updates and to provide

oversight. Belonging Matters currently oversees 13 CoS, having managed them for a

decade, while Inclusion Melbourne established 9 CoS in two years and Imagine

More has assisted setting up 50 CoS.

These providers often rely on Informational Linkages and Capacity Building (ILC)

funding from the Federal Government to execute community projects benefiting

Australians with disabilities, their carers, and families. This funding is used to cover

the costs of training and consulting with families, it does not pay for the facilitators

time to set up and run CoS.

4.2 Microboards

A Microboard functions similarly to a traditional Circle of Support, involving a trusted

group of individuals who help advocate for and realise a person's goals and wishes.

However, unlike a Circle of Support, a Microboard is a formalised and legally

recognised organisation. Shea (2001) describes it as “a non-profit society of family

and friends, committed to knowing a person, supporting that person, and having a

volunteer (unpaid), reciprocal relationship with that person” [9]. Microboards are a

supported decision-making structure that “legally recognises the process of

supporting a person with their decision making. That is, it is an alternative legal

regime to substituted decision making and a system intended to replace

guardianship” [10].

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

15

Page 15 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

4.2.1 Aim of Microboards

Microboards are small nonprofit providers established by a dedicated group of family

members, friends, and community members. They aim to provide personalised

support and advocacy for people with disabilities (PwD), focusing on their specific

needs and goals. “It's a group of people who are in a freely given reciprocal

relationship with a person with disability….who make a commitment to in a number

of principles, but the three main ones are person-centred thinking, self-determination

and reciprocal relationships” (CEO Microboards Australia).

The primary objectives of Microboards include:

1. Individualised support: finding services and support to meet the specific needs,

preferences, and aspirations of the PwD.

2. Hire support staff they choose: the MB can employ support staff for the PwD.

Within the NDIS context, the Microboard hires support staff using a self-

managed or plan-managed fund and invoice the participant for their supports.

2. Empowerment and inclusion: empowering the PwD to live more independently

and to have an inclusive life within their community.

3. Advocacy: acting as advocates for the individual's rights and needs, ensuring

they have access to necessary resources and opportunities.

4. Quality of life: enhancing the overall quality of life for the individual by providing

consistent, reliable support from a committed group of people who know them

well.

5. Self-determination: promoting self-determination and enabling the individual to

have a greater say in their life decisions and the direction of their care and

support.

6. Sustainability: creating a sustainable network of support that can adapt to the

changing needs of the individual over time (e.g., when the carers are no longer

able to help).

7. Social activities: create opportunities for the PwD to engage in the wider

community and to do fun activities with Microboard members.

4.2.2 Target population of Microboards

People suitable for a Microboard include those with intellectual or learning

disabilities, physical disabilities, complex conditions like sensory impairments, and

specific conditions such as dementia. Lack of an existing support network is not a

barrier to starting a Microboard. Providers assist by identifying close relationships in

the person's life or expanding social connections through community engagement

activities or facilitating the development of meaningful relationships.

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

16

Page 16 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

4.2.3 Key components of Microboards

Microboards in Australia are often established using the parameters outlined by Vela

Microboards Canada. These include:

1. Members must establish and maintain a personal relationship with the person

for whom the board is created.

2. All people are assumed to have the capacity for self-determination.

3. All decisions made by a Microboard will respect the person’s safety and dignity,

and reflect their needs and wishes.

4. Members must ensure the person participates in community events with

themselves or others in their network.

5. All Microboard members will conduct their board business in the spirit of mutual

respect, cooperation, and collaboration.

6. Members are there on a voluntary basis, and its understood that people may

choose to leave or take a break.

7. A Microboard is structured in a way that it can remain in place forever.

8. A Microboard is a supported-decision-making structure for people who need

support to make a decision, but not everyone does.

9. A Microboard may employ support workers for the PwD.

10. A facilitator will work with the Microboard initially to ensure they focus on the

PwD’s needs and goals, but ultimately move to a model where the Microboard

functions independently of the facilitator.

4.2.4 How providers support the formation of Microboards.

Providers of CoSAM provide a range of services to help families of a PwD establish

and maintain Microboards. These services typically include:

1. Information and education: conduct workshops and training sessions to

educate families and community members about the concept of Microboards,

their benefits, and how they operate.

2. Facilitation and consultation: offer the services of experienced facilitators who

guide the meetings and planning sessions, helping to form the Microboard.

3. Consultation services: provide ongoing consultation to address questions and

challenges that arise during the setup and operation of the Microboard.

4. Legal and administrative support: help with the legal process of incorporating

the Microboard as a nonprofit provider.

5. Compliance guidance: ensure that the Microboard complies with local, state,

and federal regulations.

6. Person-centred planning: facilitate the development of a person-centered plan

that outlines the individual’s needs, goals, and preferences, which will guide

the Microboards activities.

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

17

Page 17 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

7. Support network building: help identify and recruit family members, friends,

and community members who can contribute to the Microboard.

8. Policy advocacy: advocate for policies and systems that support the

establishment and sustainability of Microboards.

9. Networking opportunities: facilitate connections between different

Microboards to share experiences, resources, and best practices.

10. Evaluation tools: provide tools and frameworks for evaluating the

effectiveness of the Microboard and the well-being of the individual it

supports.

4.2.5 Legal responsibilities

The following describes who might generally bear legal responsibility:

1.

The Microboard as an entity: if the Microboard is formally incorporated, it

operates as a legal entity. This means the Microboard itself can be legally

responsible for decisions and actions taken in its name.

2.

Board members: individual members of the Microboards board of directors

have a fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of the PwD. They can be held

legally responsible for decisions made by the board, especially if those

decisions result in harm or are found to be negligent.

3.

The PwD: the PwD is also a board member and bears some responsibility for

board decisions. However, their legal responsibility may be limited by their

capacity to understand and make informed decisions, and this is often taken

into account in legal considerations.

4.

Third parties: when working with third parties, the Microboard as a whole is

typically legally responsible for agreements and decisions

5.

Ethical responsibility: members of the Microboard (and CoS) bear ethical

responsibility for ensuring decisions align with the PwD's best interests. This

ethical responsibility does not always equate to legal liability.

4.2.6 Time required to set up Microboards.

Setting up a Microboard typically spans several months to two years, including

consultations with families to determine suitability, preparation of necessary

documents, exploration of potential members, provision of member training, and

selection of a facilitator. The process of choosing members for the Microboard can

be a lengthy process, often employing relationship mapping techniques to categorise

individuals in the person's life who “care about the person, know the person and

either understand or are able to engage in a process of understanding the principles

which underpin Microboards” (CEO, Microboards Australia). Often families will think

they need professionals on the board, such as lawyers and doctors, but “part of our

role is to help them to understand that you can outsource all of that support” (CEO,

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

18

Page 18 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

Microboards Australia). For individuals lacking a robust support network, time is

allotted to cultivate new relationships that may lead to potential board invitations.

4.2.7 Costs for Microboards.

Microboards Australia estimates an annual operational cost of $8,400, covering 84

hours of facilitator time and delivery of workshops to train new members on how to

run Microboards and supported decision-making ($100 per hour). Facilitators help

establish the Microboard (approximately 2 years) and may attend a few meetings,

but they mostly run independent of facilitators.

Ongoing training and education provided by Microboards Australia is estimated to

cost $3,800 per year.

Setting up a Microboard in British Columbia only costs $130 for non-profit

incorporation and $40 annually thereafter. Vella Microboards provide free mentoring,

including training and ongoing advice to Microboard members. Vella is funded by

Community Living British Columba (CLBC), that allows them to provide free services

to families: “if those 750 people didn't have a free resource in Vella, then there

definitely would be more cost associated with them trying to figure out how to move

forward and how to set things up and how to proceed” (Executive Vella

Microboards).

4.2.8 Hiring employees.

Microboards can hire support staff who assist in the home for PwD. In British

Columbia the majority of Microboards take on this responsibility. However, in

Australia, only 4 of the 20 Microboards do this. In such cases, the Microboard will

pay the salary of the support worker and invoice the PwD who then claims this

money from the NDIS and repays the Microboard. For this to happen the PwD needs

to manage their own funds. Microboards Australia emphasises that “this has since

proven to be a reliable and robust way of engaging support teams and providing

individualised supports which are not solely dependent on the parent of person with

disability, and have the added transparency and accountability of oversight by a

responsible board” (CEO, Microboards Australia). For the remaining PwD who have

a Microboard, but do not employ staff, the carer will take on the task of hiring support

workers.

Part of the role of Microboards Australia is to advise members of Microboards who

wish to hire support staff, by providing “substantial support around legal engagement

and management of paid support workers” (CEO, Microboards Australia).

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

19

Page 19 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

Some Microboards may face a barrier in needing to pay for insurance to protect

themselves in cases of workplace injuries or breakdowns in employee relationships

“you never want to have a legal entity in place without insurance…. it provides that

safety net for families, for the person, right, especially in situations where there's a

breakdown in the employee relationship, or there's some sort of injury in the

workplace” (Board member and lawyer, Microboard Ontario).

Having a Microboard and insurance can help families mitigate risk effectively: “If the

family's been managing four or five workers for 20 years and they've had funds

flowing through their accounts and they've had no insurance and no employment

agreements or contracts ….this is just a way to make things easier….and to set up

proper controls, proper operating environment” (Board member and lawyer,

Microboard Ontario).

The cost of insurance for a Microboard in Australia can vary widely depending on

factors such as the size of the Microboard, the activities it undertakes, and the

specific insurance coverage required. Typically, insurance costs for nonprofit

providers like Microboards can range from a few hundred to several thousand dollars

per year. “So there is this myth that it's hard and it's more expensive, but I do think

it's a bit of a myth” (Board member and lawyer, Microboard Ontario).

4.2.9 How Microboard providers function and who runs them.

In Australia, Microboards Australia employs 20 team members, including 8 full-time

staff and 12 facilitators, and has received ILC funding for the past 4 years. This

funding supports their activities in establishing Microboards, training members, and

pairing individuals with one of their 12 facilitators. Once a Microboard is established,

Microboards Australia steps back and offers support as needed, such as legal

engagement and management of paid support workers. Currently, there are 20

Microboards in Australia.

In Canada, Vella Microboards receives government funding from Community Living

British Columbia, enabling them to provide services at no cost to people with

disabilities and their families. They currently support 750 individuals and in the last

year signed up 70 new Microboards, but lack the capacity to oversee every

Microboard closely: “it's not like we have the capacity to chase people down and

make sure they're actually doing things properly” (Executive, Vella Microboards).

4.3 Findings relevant to both Circles of Support and

Microboards

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

20

Page 20 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

4.3.1 How CoSAM ensure they provide supported decision-making

There is a history of people with disabilities not being supported or enabled to make

decisions for themselves. This is based on the idea that because a person can not

communicate, that the person doesn’t know how to or want to make decisions.

Because of this, people with cognitive impairment are often left out of decisions

about their lives and rely on other people to make decisions for them, known as

substituted decision-making. These decisions are generally made in the person’s

perceived ‘best interest’, however, this does not necessarily mean their will and

preference has been considered.

Microboards and Circles of Support ensure they provide supported decision-making

rather than substituted decision-making through various practices and structures that

prioritise the preferences of the individual they support. This includes:

1.

Person-centred planning: centre all planning and decision-making processes

around the individual's needs, preferences, and goals.

2.

Active participation: involve the individual in all discussions and decisions to

the greatest extent possible, ensuring their voice is heard and respected. The

individual is encouraged to attend the meetings and are a member of the

CoSAM.

3.

Trusted relationships: a CoSAM is composed of family members, friends, and

community members who know the individual well and have their best

interests at heart.

4.

Role clarity: clearly define the roles of each member to ensure they are there

to support, not override, the individual's decisions.

5.

Effective communication: use communication methods that are accessible

and understandable to the individual, including plain language, visual aids, or

assistive technologies if needed.

6.

Patience and time: allow the individual time to express their thoughts and

make decisions, without rushing the process. Individuals may decide

sometime after the meeting when the facilitator gets back in touch.

7.

Risk and responsibility: respect the individual's right to take risks and make

mistakes, recognising that this is a normal part of learning and personal

growth. Encourage them to make their own choices and take control of their

life decisions, even if those decisions differ from what others might choose.

8.

Facilitated decision-making: When necessary, facilitate decision-making by

breaking down complex decisions into smaller, more manageable steps and

providing support at each stage.

9.

Ongoing assessment: regularly review and adapt the support provided to

ensure it continues to align with the individual's evolving needs and

preferences.

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

21

Page 21 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

By implementing these practices, CoSAM can create an environment where the

individual is empowered to make their own decisions with the necessary support,

rather than having decisions made for them.

“That in many ways because of how a circle is set up, it actually embodies so much

of supported decision-making in its structure. It's almost like it's got a bit of an idiot

proof thing to it because the fact that you have the regularity, the people, the checks

and balances, the structured meeting, the agenda that you have, the goals, [and]

that you've gotta work towards the external accountability…..So even if you've got

people who have got no understanding [about] support theory,….as long as the

structure of the circle functions well, you've got the regularity, the checks, the goals

and the Facilitator teaching training [there is] a chance for them to catch up with

others. And you already have that machine happening of supported decision-

making” (head of research and policy, Inclusion Melbourne).

Interviews with representatives from CoSAM providers in Australia and Canada

revealed that the approach to supported decision-making varies depending on the

individual's ability to communicate. “Someone might need to make a decision using

pictures, they may need to make a decision [by] going and visiting something”

(Director, Belonging Matters), but maintained it is possible “…regardless of, you

know, the impact of the disability, I think there's always a way and it's just doing that

deeper thinking to make sure that the person is involved” (Director, Imagine More)

Supported decision-making training for facilitators provided by Inclusion Melbourne

integrates several models, focusing on:

• Recognising a person’s past experiences and options, and reinforcing these.

• Identifying decisions that need to be made or could be made.

• Emphasising the importance of making decisions now to achieve long-term

goals.

• Expanding the range of choices and experiences available to the person.

• Engaging the insights of supporters, family members, etc., to discern the

person’s will and preferences.

• Considering potential consequences of decisions.

• Empowering the person to make decisions independently or with support.

• Reviewing and learning from decisions made.

Other strategies employed by CoSAM to facilitate supported decision-making

include:

• Encouraging the PwD to write a manifesto outlining how the CoSAM can

support them in decision-making.

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

22

Page 22 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

• Actively involving the PwD in attending meetings.

• The PwD collaborating with the facilitator to set the agenda for meetings.

A successful outcome for CoSAM, as highlighted by Belonging Matters, is a shift in

the PwD’s decision-making capability to articulate their genuine preferences. PwDs

often respond saying “yes” to all suggestions, but when they start to say "no," it

shows they’re more discerning about their true desires and choices. A facilitator from

Belonging Matters said “[when they say “no”] then I know we've got some decision-

making going on and persons confident enough to start to articulate their true

preference and know that it's a safe place to acknowledge their real preference and

also a safe place to challenge and to grow”.

Supported decision-making is integral to self-determination, by empowering

individuals' capacity to make choices. Within a CoSAM, understanding a person's

history is crucial to comprehending their decision-making abilities and preferences.

This includes assessing whether past experiences, such as exposure to punitive

environments, may influence their current decision-making processes and

understanding of personal likes and dislikes. “Unfortunately often with or usually with

adults that have been through special education in Australia, very little is actually

known about their likes and preferences. So, we kind of paused there and go what is

not known about the person and how can we find out more about what they like and

dislike and how they express those preferences in their life?” (CEO, Microboards

Australia).

Regarding legal frameworks, Australian policies and practices on substituted

decision-making were reviewed by the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC)

in 2014 [11].They recommended reforms to uphold the rights of PwD to make and

have their decisions respected. The NDIS adopted the ALRC’s advice and

developed a Supported Decision-Making policy in 2023 that states “That all

participants, including people with profound intellectual and multiple disability, have

the right to support to make or direct decisions that impact their lives”[5].

4.3.2 Challenge to provide supported decision-making

Providing supported decision-making within CoSAM presents significant challenges,

particularly when faced with scenarios such as: 1) the PwD lacking awareness of the

consequences of their decisions, for instance, regarding financial control, as

highlighted by the statement, "the person could actually be making detrimental

decisions for themselves, you know, because they've never had any other life

experience." (Director, Belonging Matters); or 2) the inherent difficulty some PwD

face in decision-making due to cognitive limitations, as noted by a facilitator, "they

may need support, generally speaking, to hold and maintain any conceptual

information" (Facilitator, Belonging Matters).

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

23

Page 23 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

Belonging Matters recognises the ongoing challenge of avoiding substituted

decision-making within CoS, acknowledging, "it's a good question 'cause there's a

risk of that all the time" (Facilitator, Belonging Matters). Despite this, facilitators strive

to uphold the autonomy of the PwD by emphasising, "[we] try [our] utmost to always

refer back to the person making the decision…[and ask] what it is they want out of

that…and let us know when you figure that out…and we can figure out the strategy

around it" (Facilitator, Belonging Matters).

Microboards Australia acknowledges there are risks for a board to be controlling the

person or family, or making decisions to the exclusion of the person’s voice. “For

example, we have seen a number of constitutions developed by other people where

the decision making of the board is named as ‘voting’ in the constitution. This is

frankly dangerous – we should not be ‘voting’ on decisions about a person with

disability’s life” (CEO, Microboards Australia). To prevent this, facilitators at

Microboards Australia will not progress the incorporation of a Microboard unless all

board members understand the principles of self-determination, have demonstrated

a capacity to uphold them and have a demonstrable culture of including and hearing

the PwD. However, there is the potential for things to change overtime within the

CoSAM, especially when facilitators move on and there is no external person

overseeing the inner workings of the group.

Another hurdle in supported decision-making involves ensuring individuals outside

the Microboard are aligned with these principles. Microboard Australia addresses

this by "creating a culture in the entire system around the person that helps prevent

substituted decision-making" (CEO, Microboard Australia).

Conversely, in Ontario, Canada, there is no legislative mandate for CoSAM

members to provide supported decision-making; instead, it operates on "principles,

values, and best practices…[with] nothing really in legislation" (Director and lawyer,

Microboards Ontario).

4.3.3 Working with third parties.

When collaborating with third parties, Microboards legally bear responsibility for

decisions made. The PwD is also a board member and shares accountability for the

board's decisions.

Of interest, Microboards Australia has partnered with the Centre of Excellence in

NSW to tackle human rights issues within Australia's health system. They are

offering training on the role Microboards can play in advanced planning for PwD,

especially when hospitalisation may be necessary.

4.3.4 Facilitation for CoSAM.

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

24

Page 24 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

One of the critical skills of a good facilitator, is understanding and knowing how to

make use of the services, tools and opportunities provided within the NDIS,

communities, service providers and government. The head of policy and research at

Inclusion Melbourne states “having that ability to use these tools and systems and

planning, that then becomes the next real driver”.

When the CoS is ready to become independent of a paid external facilitator, a

member will step into the role. Ideally, this not a family member so they can

participate in the discussions and avoid the challenging task of requesting help from

other members (Imagine More and Belonging Matters).

Most providers highlighted the difficulty of finding good facilitators due to the

complexity of the role and the need to work flexibility outside of office hours.

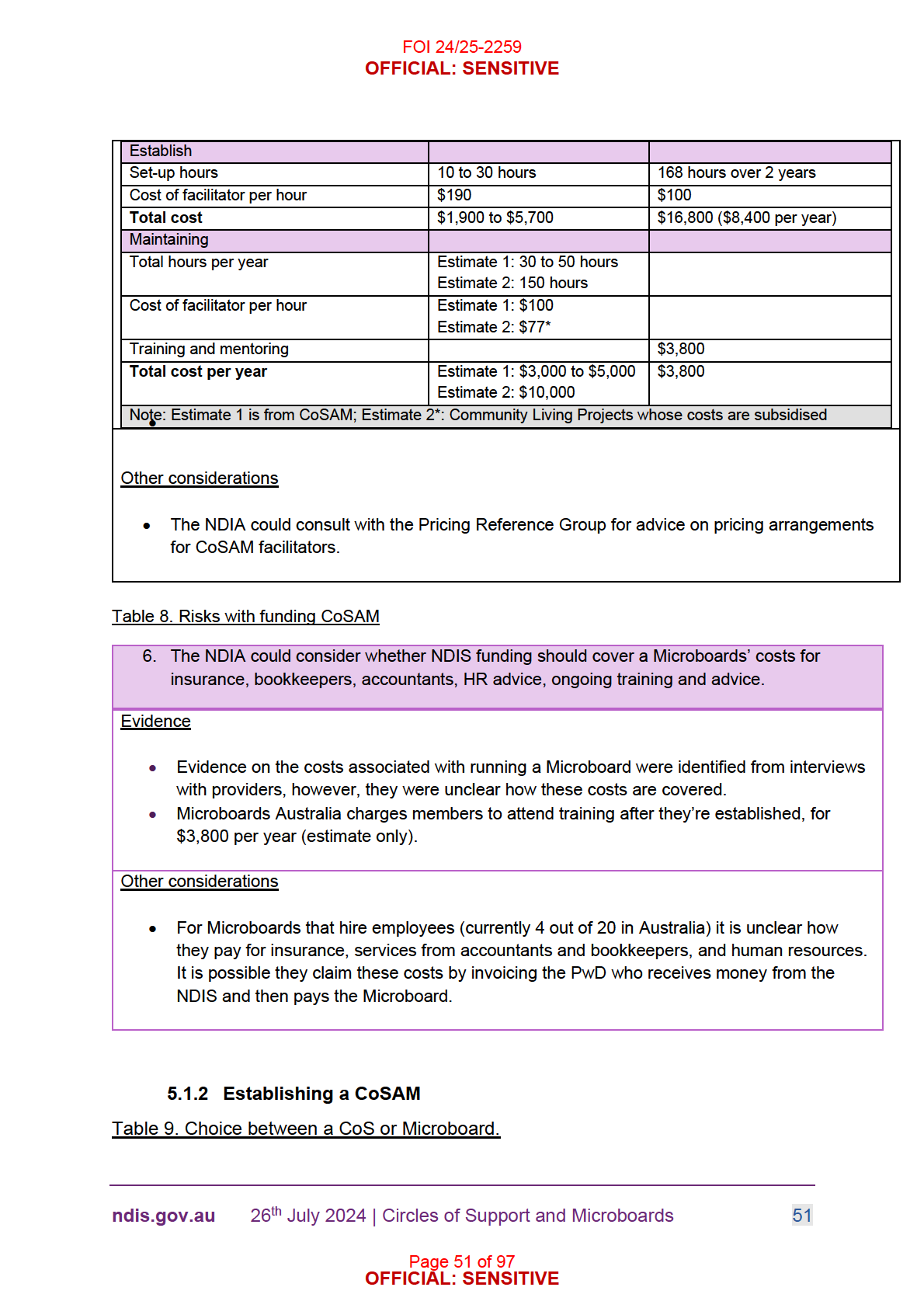

1.1.1 Cost of facilitators

When CoSAM providers discuss 'funding Circles and Microboards', they primarily

focus on funding the facilitators. It costs approximately $10,000 a year for a CoS

facilitator and $8,400 a year for a Microboard facilitator and for training board

members. These costs will vary depending on the provider and level of need of the

PwD to establish a CoSAM.

1.1.2 Safeguarding provided by CoSAM.

Circles and Microboards play a crucial role in safeguarding by ensuring that services

provided are supportive and safe for individuals, keeping their needs at the forefront

of planning, establishing succession plans, fostering community connections, and

acting as a natural safeguarding mechanism by consistently bringing people together

around a PwD. According to Jay (2018), "Circles of Support are seen as

mechanisms that can enable and safeguard the individuals’ rights to make decisions

and choices about their own lives and support arrangements"[12].

Safeguarding principles are integral to the Microboards constitution, where members

actively monitor and protect the physical and mental wellbeing of the PwD (CEO,

Microboard Australia). Some members conduct unannounced visits to check on the

PwD's wellbeing, reflecting the CoSAM's culture of deep familiarity with the

individual. As stated by the CEO of Microboards Australia, "So everyone knows the

signs of things going well and the signs that things are not going well and that gets

unpacked." Additionally, wellbeing assessments are regularly conducted and

reviewed by the Microboard, measures include the PwD’s engagement,

presentation, mental wellbeing, and physical health.

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

27

Page 27 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

An important goal of the CoSAM is to continue across the individual’s lifetime, to

ensure they receive ongoing support and care even when the family are no longer

alive. While CoSAM inherently act as a safeguarding strategy, Microboard Australia

CEO emphasises the importance of the PwD selecting their Microboard members

willingly, "we're really clear about this, that Microboards and Circles for that matter,

can easily become things that are done to people."

Microboards Australia recognises the potential risk of Microboards becoming

controlling, and therefore they assess prospective members to ensure they share the

right mindset. The CEO emphasises, "we're pretty clear that we won't progress with

a Microboard and supporting its incorporation if we don't see evidence that the

supporters have got the right mindset because a group of people can be a wonderful

thing in a person's life, they can also be a very controlling thing actually."

CoSAM provide safeguarding through:

1.

Personalised oversight: because CoSAM are composed of a small group of

individuals who know the person well, they can closely monitor their well-being

and quickly identify any concerns.

2.

Comprehensive planning: CoSAM develop individualised plans that address

the specific needs, preferences, and vulnerabilities of the person they support.

3.

Accountability and transparency: Microboards operate with a high level of

transparency and accountability. Having regular meetings and keeping

minutes can ensure all actions are in the best interest of the individual.

4.

Empowerment and advocacy: by empowering the individual and advocating

for their rights, CoSAM can help to protect the person from abuse, neglect, and

exploitation. They work to ensure that the individual has a voice and can

express their concerns.

5.

Training and education: CoSAM members and facilitators receive training on

safeguarding principles, shared decision-making, recognising signs of abuse

or neglect, and responding appropriately to concerns.

6.

Community involvement: by engaging with the CoSAM community and

service providers, CoSAM help create a larger support network around the

individual, that further enhances their safety.

7.

Regular reviews and updates: the plans and strategies implemented by

CoSAM are regularly reviewed and updated by the members so they can

identify and respond to any pressing issues.

1.1.3 Sustainability.

Training is offered to CoSAM members and facilitators by providers to guide them on

supportive decision-making, social valorisation (ideas that aims to make positive

change in the lives of people who are disadvantaged because of their status in

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

28

Page 28 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

society) and how to promote sustainability. Other topics may include establishing a

CoSAM, the role of the facilitator, planning the first gathering, creating a positive

culture, letting a Circle grow naturally, how to make it fun and to do things outside

the circle (Inclusion Melbourne, Imagine More). Inclusion Melbourne offers 6-hour

training for facilitators.

Holding the CoSAM accountable can be an effective strategy to ensure their

sustainability. Belonging Matters requires the CoS to establish a plan at the

commencement of each year based on what the PwD would like to achieve, and

then review progress against the plan. It is important the CoSAM work towards a

specific goal to give the CoSAM a sense of purpose (Imagine Melbourne).

Sometimes members of a Circle may only participate for the duration it takes for the

PwD to achieve a particular goal, i.e., fulltime employment (Imagine More, Belonging

Matters), or for the time the PwD is at school (Imagine More). Thus, the selection of

Circle members may depend on the goal of the PwD at the time (i.e., school friends

to include PwD in social activities). Inclusion Melbourne provides some guidance on

how members may withdraw from the Circle.

1.1.4 Considerations for CALD and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

people

Belonging Matters is one provider that describes the demographic of the circles of

support they have created. The majority are described as non-CALD families. Of the

16 of Circles established with Belonging Matters since 2015, ten are non-indigenous

Australians, two have Jewish backgrounds, one Polish, one New Zealand, one

British, and one Italian. The two people from Jewish backgrounds have strong

cultural and religious roots and values, providing some evidence that the CoS can

work for people from CALD backgrounds.

Imagine More claimed they not any need to adjust their approach for setting up a

CoS for cultural reasons but the CEO commented they are sensitive to the needs of

people with CALD backgrounds “but we would be, you know, aware of that and…

what sort of considerations that they would want and what would be important”.

The concept of establishing a formal network, such as a CoSAM, to support a PwD

may seem unfamiliar to First Nations people (CEO, Microboard Australia). They may

already have a healthy, inclusive, community culture that provides a support network

for the PwD and their family “We see it very much as our community is a collective

community. Supported decision-making for a person that has a disability or doesn’t

have a disability is often the same. It’s always a group consensus about what can

and can’t be done particularly in more rural, regional and remote communities.. And

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

29

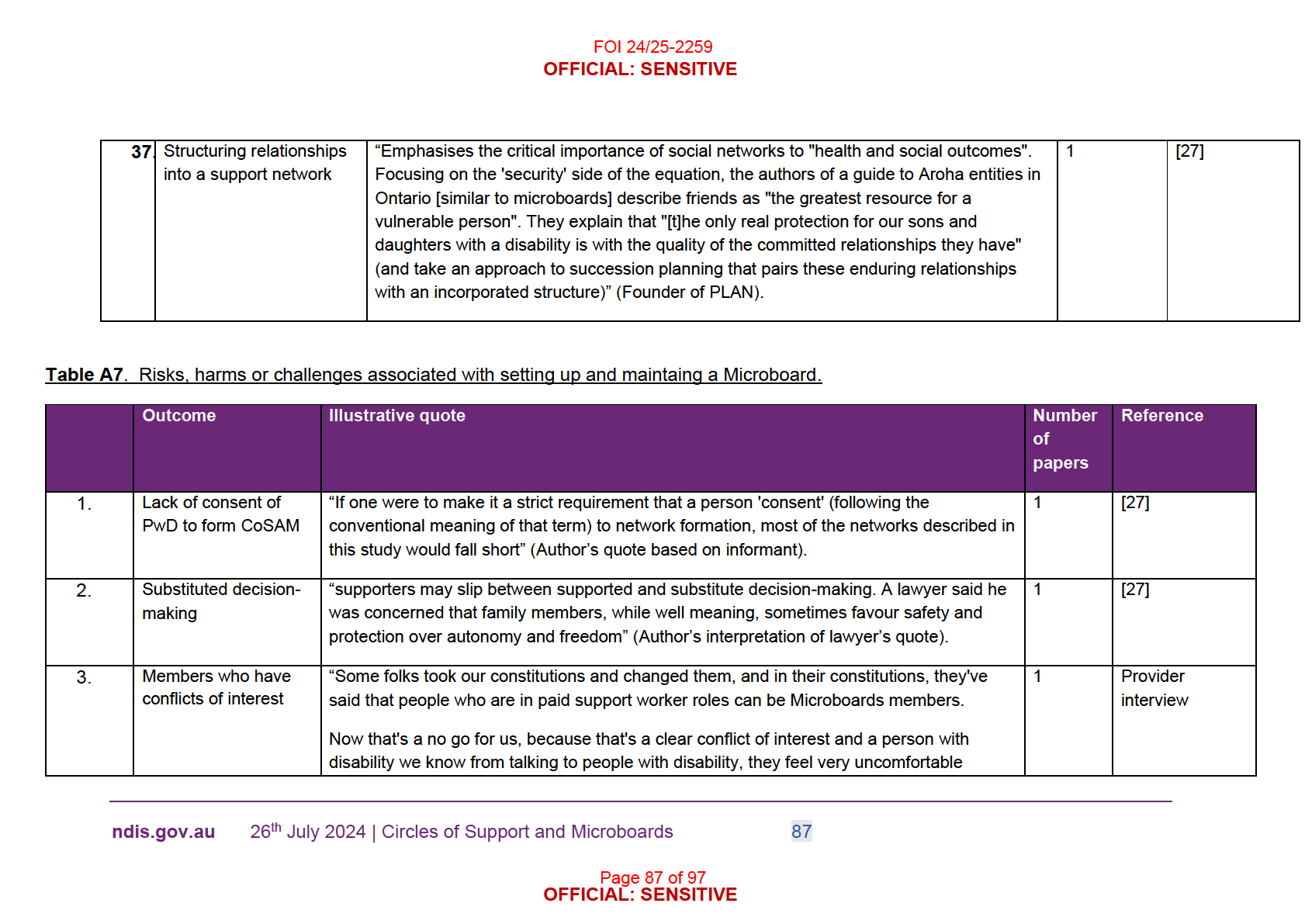

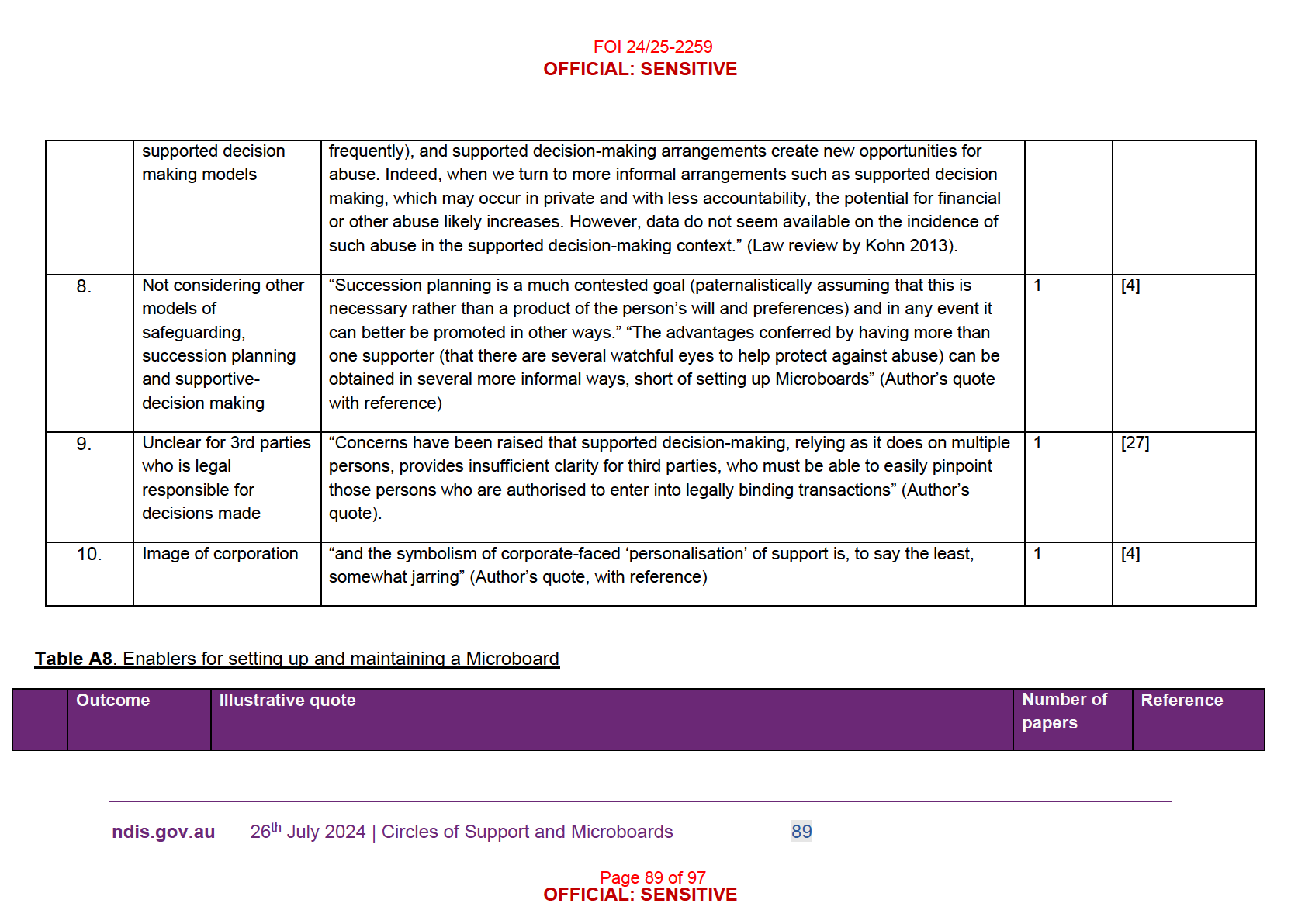

Page 29 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

literally we do sit and decide who is going to make the decision and who needs to be

involved in that decision-making process. And it doesn’t mean that we’re taking away

the autonomy of the individual. The individual is still centred but the decision is

collectively made about what’s best for that person. And literally it is our way of doing

the circle of support whether you have a disability or not…” (First Nations person)[4]

The barriers faced by First Nations peoples was briefly considered in the

Commonwealth Department of Social Services commissioned report on supported

decision-making. That research made the point that due to the mistrust in the sector,

‘Capacity building must also be sensitive to historical and current factors affecting

the relationship between communities and government/services’ [13].

The NSWLRC noted that supported decision-making aligned closely with the:

collaborative and communal style of decision-making in First Nations communities,

particularly where there are multiple supporters. However, somewhat different from

supported decision-making an individual’s decision is often thought of as a decision

by and for their whole family or community group [13].

Guidance for providers by the Office of the Public Advocate (VIC), on interacting with

First Nations clients may be helpful when exploring supported decision-making in

various contexts [14].

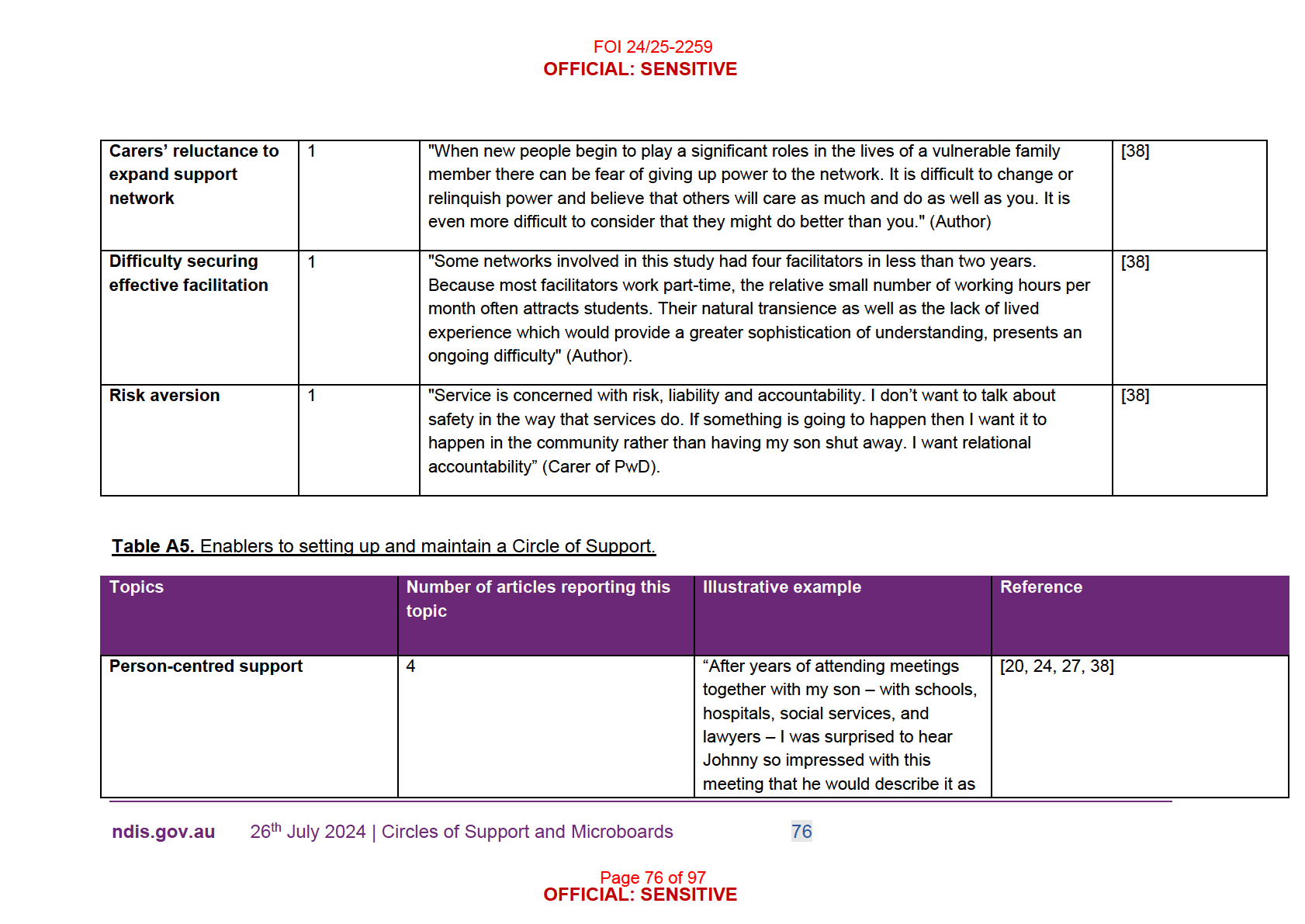

1.1.5 Challenges experienced by CoSAM providers.

CoSAM providers in Australia described the challenges they experience when

setting up and maintaining a CoSAM for participants. The following paraphrases

what providers have claimed in reports and in interviews. They included:

1.

Inconsistent decision-making by NDIS planners: inconsistent decisions

made by planners about whether to fund facilitators for CoSAM is a source of

frustration for providers, families and the PwD. Some planners may approve

it, whist others may not. Additionally, it may be funded one year but refused

the following year. An email (June 2024) from a Support Coordinator to a

facilitator about an individual with an intellectual disability (who has two

parents who are intellectually disabled), who had a circle funded for 18

months said, “at this stage she [the planner] confirmed funding for circle

meetings is declined until they have explored it further”. The funding was

denied because the planner believed a facilitator is a duplication of services

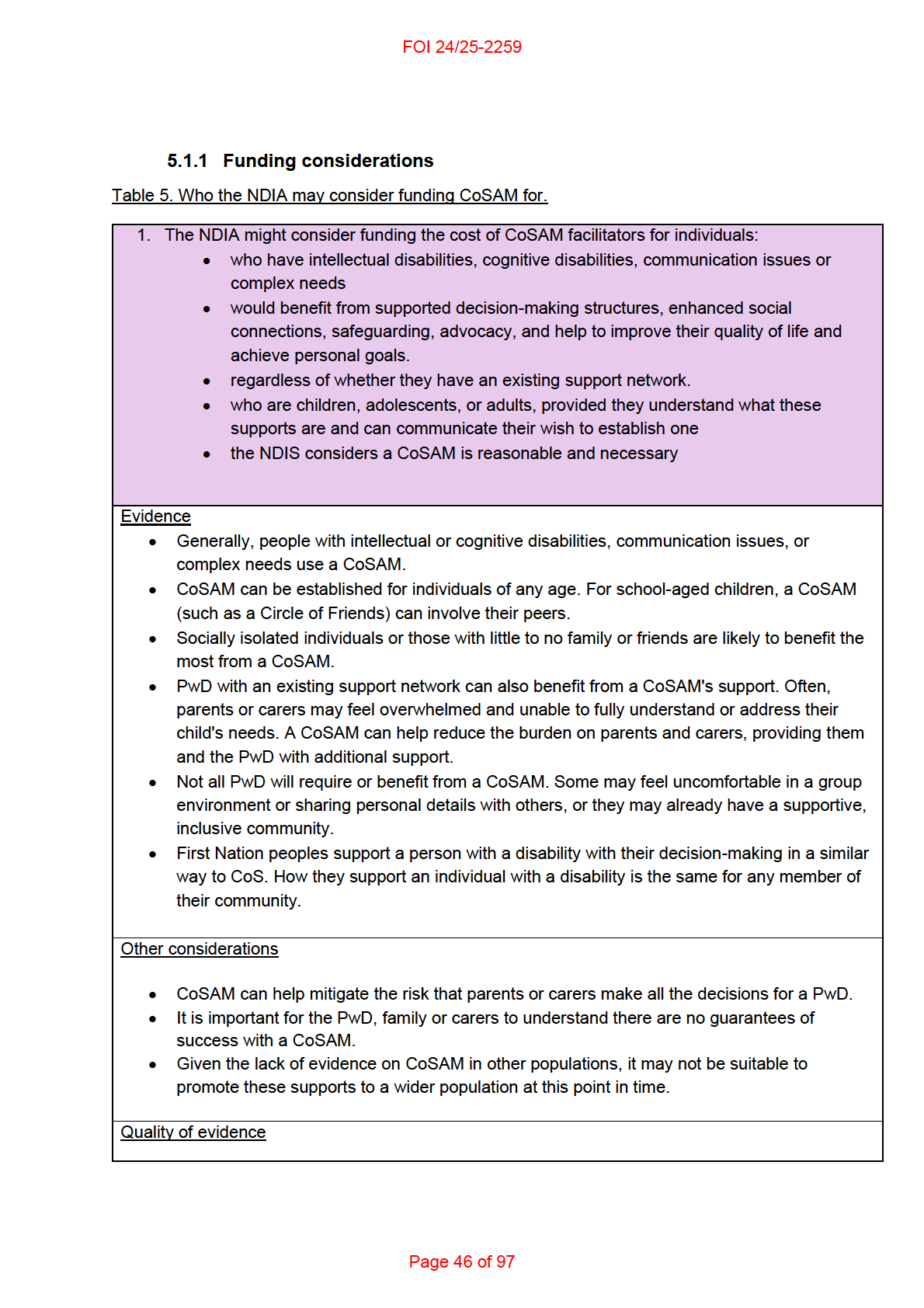

provided by support coordinators.

In other instances, it’s because they believe the PwD has friends and doesn’t

need a facilitator. This may lead to a breakdown of the CoSAM and impact the

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

30

Page 30 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

PwD and their carer’s wellbeing.

2.

Funding facilitators using the support coordinators budget: NDIA agreed

in 2021 that facilitators could be funded using the line item of Support Co-

ordination level 2. However, this led to no Microboards being approved. While

CoSAM facilitation may include elements of support coordination, providers

claim one is not a stand-in for the other. Currently, there is no line item for a

CoSAM facilitator. Requests for funding a CoSAM are currently going via the

Technical Advice and Practice Improvement Branch and since January none

Microboards have been approved.

The differences between services provided by a CoSAM versus support

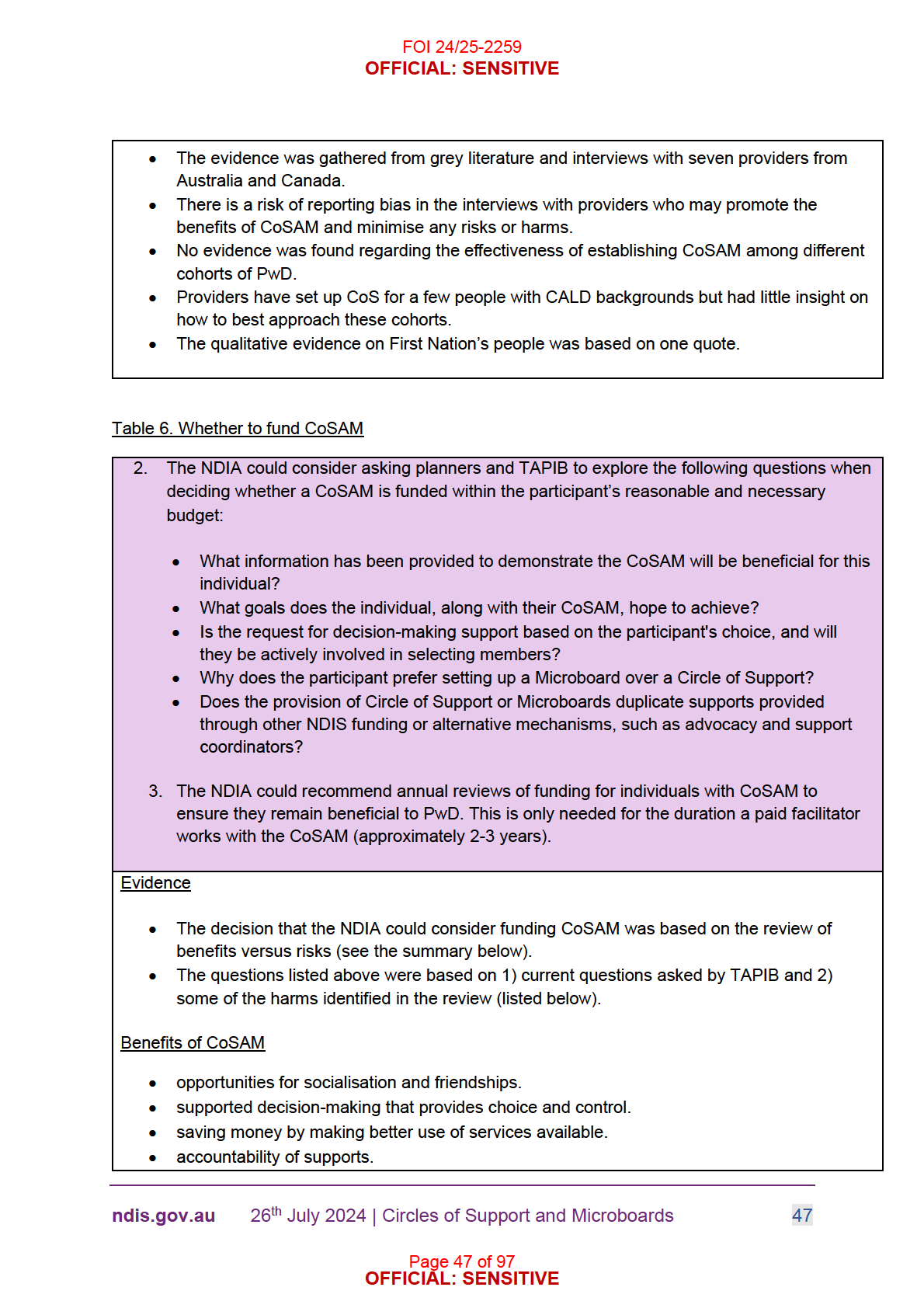

coordinators are:

o Support coordinators have a greater knowledge and understanding of

the NDIS.

o CoSAM support the PwD to choose a service or provider that their

support coordinator has found.

o CoSAM advocate with the PwD if they are not being heard by a

service.

o CoSAM can explore lifestyle options for the PwD that are outside of the

NDIS goals.

o Support coordinator’s role is time limited.

o CoSAM can spend more time exploring what a PwD wants or needs in

all aspects of their life.

3.

Assuming role of CoSAM is only for supported decision-making: while

CoSAM practices supported decision-making, it is inaccurate for NDIS

planners to view CoSAM as merely a supported decision-making mechanism.

CoSAM offers much more, including safeguarding, advocacy, social activities,

community connections, and inclusion, among many other benefits.

4.

Do not understand the value for money: there is a lack of understanding

regarding the value for money a CoSAM can provide compared with

treatments with therapists. For instance, CoSAM can reduce the need for

other supports such as occupational therapy, attending day centres.

5.

Overreliance on therapeutic solutions: the focus on clinical or therapeutic

solutions to help PwD, such as occupational therapy, has diminished the

importance social networks or close relationships have in helping a PwD

achieve their goals.

6.

Lack of guidance for planners: NDIA planners receive little training on the

benefits of CoS, despite how they align with NDIS goals “and it it's very odd

because the goals of the NDIA, for example are, [a] good life in community,

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

31

Page 31 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

social or economic, all of that. And yet what's happening in practise on the

ground is completely different. And this, you know, cause it filters down

through planners. If they haven't had training” (Director, Belonging Matters).

7.

Disability sector’s misconception of what is possible for PwD: many

(NDIA planners, families and the disability sector) fail to believe a PwD can

contribute socially and economically to society “it's countercultural at this

stage still, because culturally in the disability sector, as babies, you know,

people are still being told that what is on offer is segregated options. Planners

are telling people they can't live on their own” (Director, Belonging Matters).

“…what we're doing is trying to work in a paradigm that isolates, segregates

and has such low expectations of people with intellectual disability” (Director,

Belonging Matters).

8.

Lack of funding for facilitators may compromise access to other

supports or CoSAM: PwD will typically pay the facilitator’s fees out of their

NDIS capacity building or core supports budget. Some families have had to

decide whether to use their limited funds for therapeutic support (i.e.

occupational therapy) or a facilitator because they didn’t have enough funds

for both.

9.

The need to advocate for families who have had CoSAM funding denied:

because so many families have CoSAM funding denied by the NDIS, it places

additional strain on providers such as Inclusion Melbourne to advocate for

them “And I'm pretty good with supporting families to get funds for the circle

facilitated. But the average person struggles. Really often it's not because of

the circle that they've requested funding for is poorly put together. It's often

because they just struggle to articulate all this complexity” (Head of research

and policy, Inclusion Melbourne).

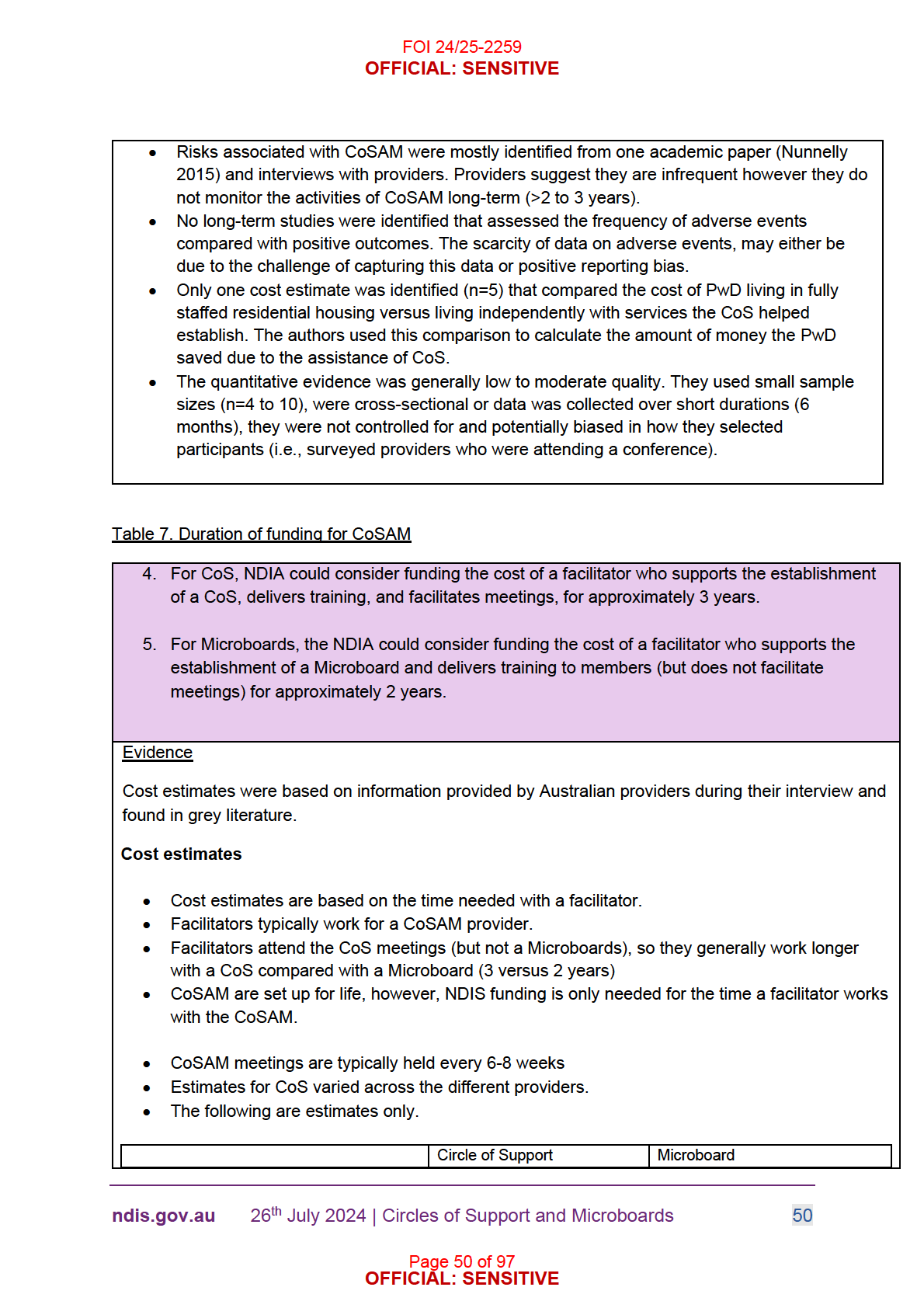

2. Microboards versus Circles of support

A Circle of Support may be a good option when the person has a strong existing

support network and there’s no need to progress to a Microboard.

A Microboard may be a good option when the person: 1) does not have a strong

network of existing supports, such as family or friends, 2) requires management and

oversight for various aspects of their life, 3) needs more structure and reliable

checks and balances, 4) needs strong advocacy, 5) wishes to formalise their support

for when their parents are no longer alive, 6) has a Circle of Support at risk of falling

apart, 7) has parents who no longer want to self-manage NDIS funds and prefers a

Microboard acts as a provider to hire support workers and handle fiscal, legal, and

practical responsibilities, 8) has people in their life with financial and reporting

expertise and 9) has people in their life willing to be part of an incorporated entity.

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

32

Page 32 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

3. Outcomes for Circles of support and

Microboards

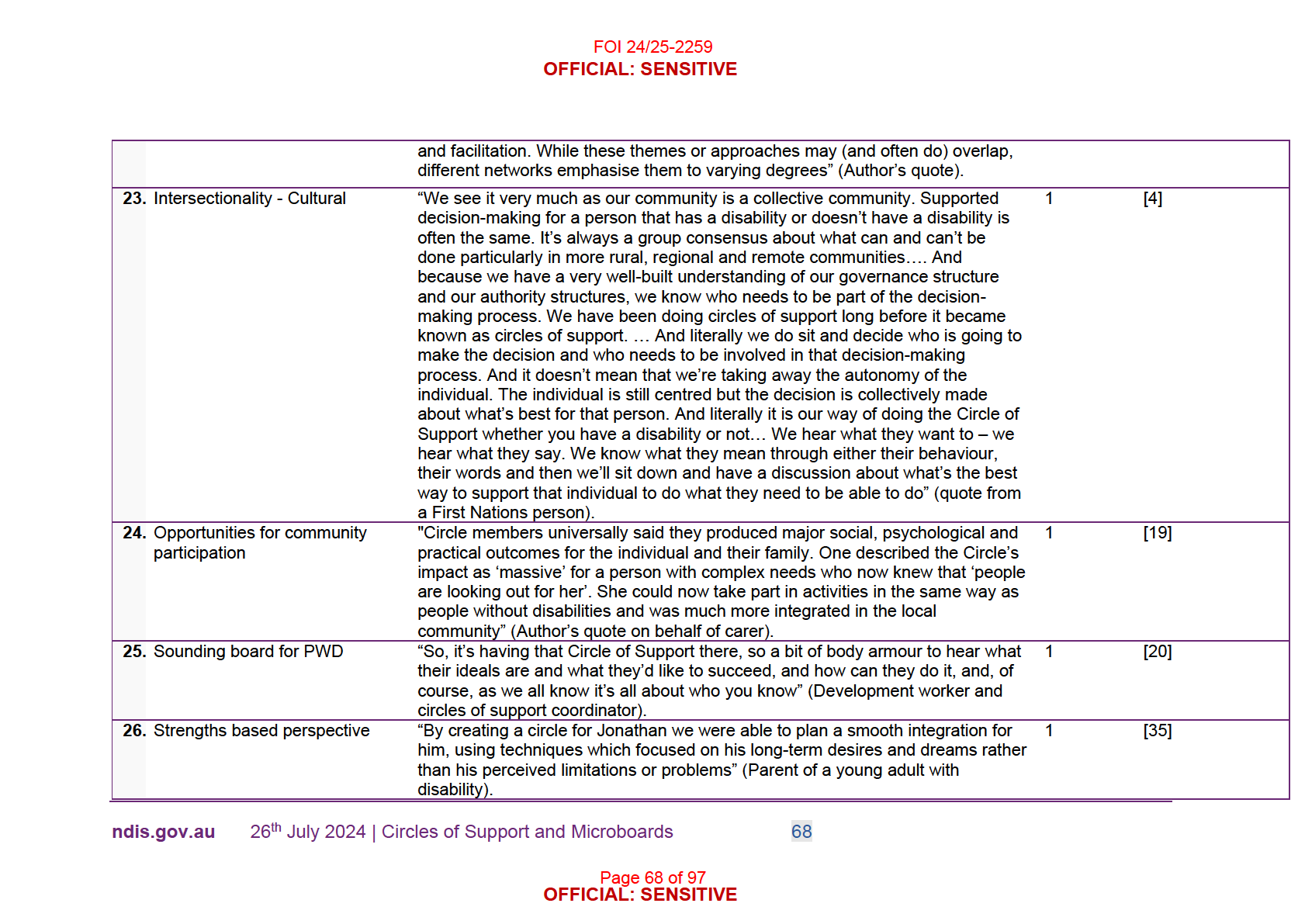

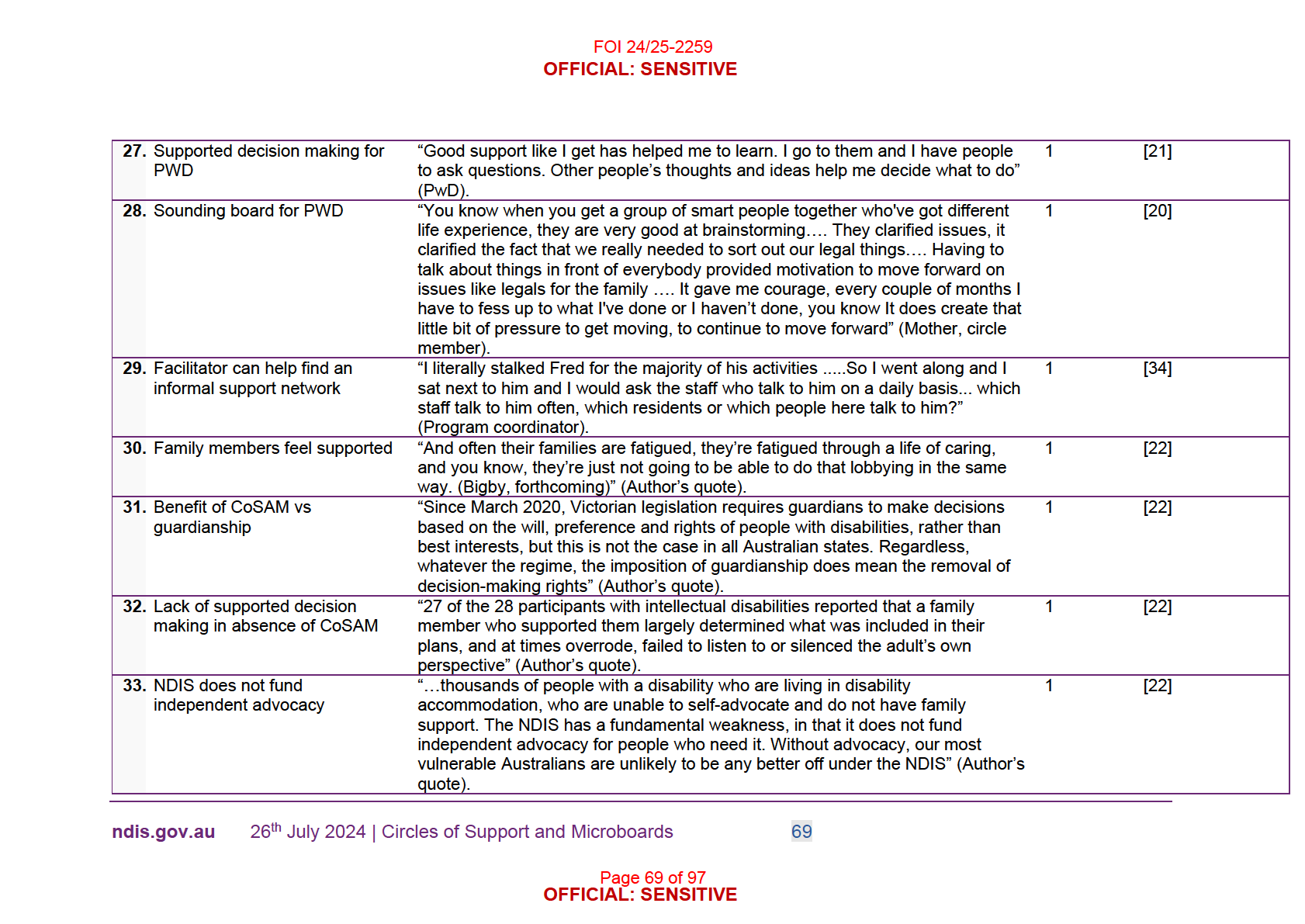

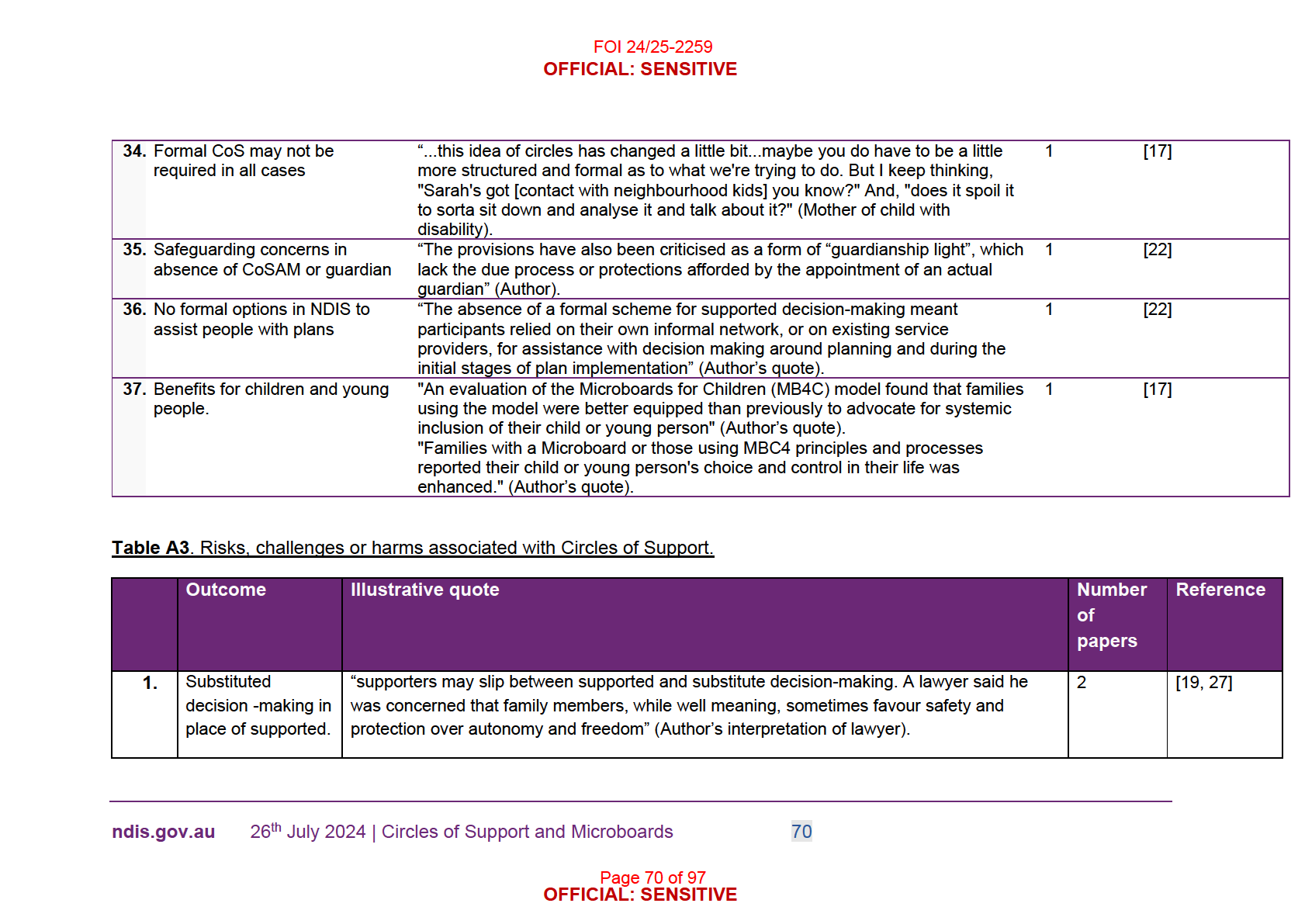

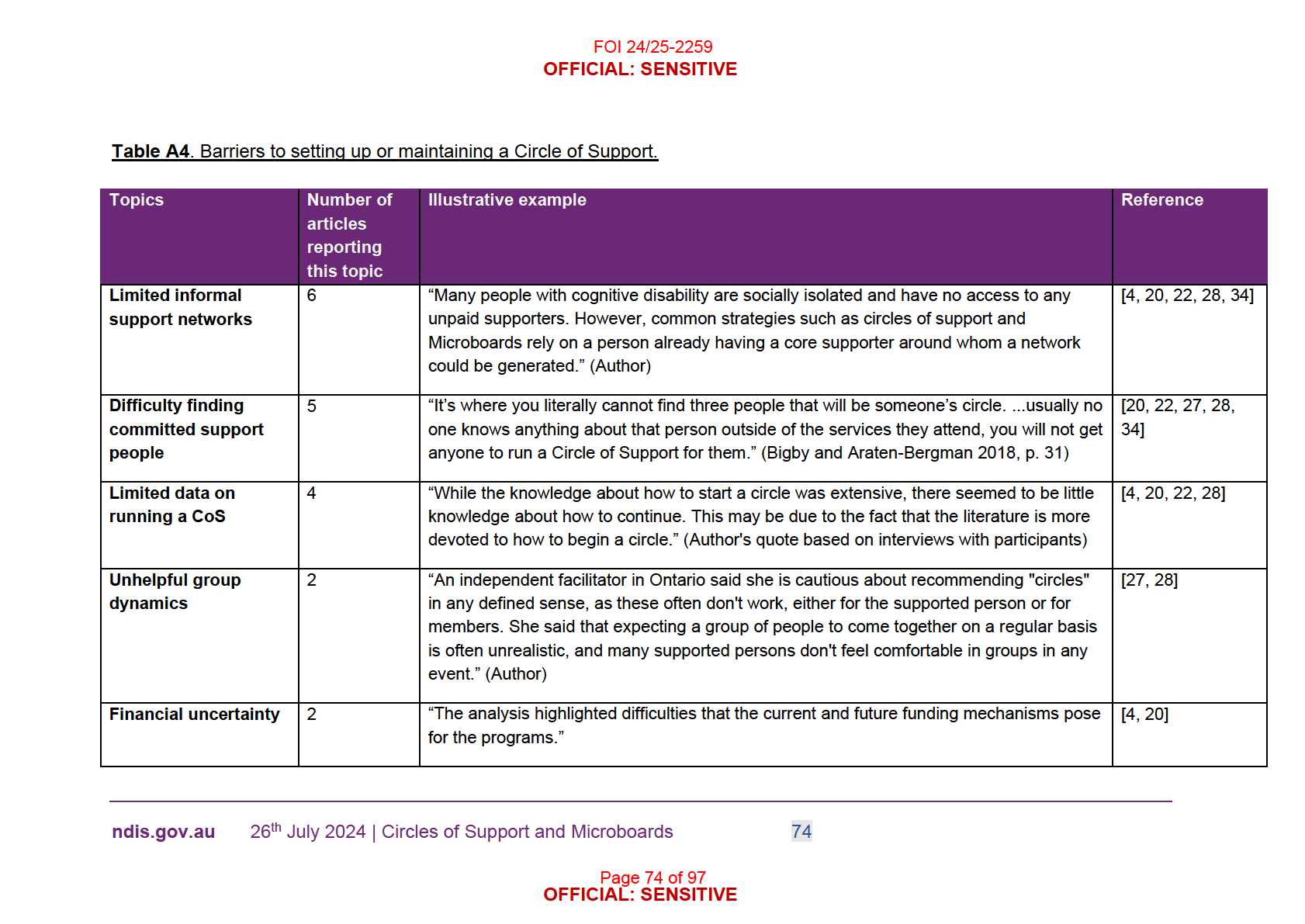

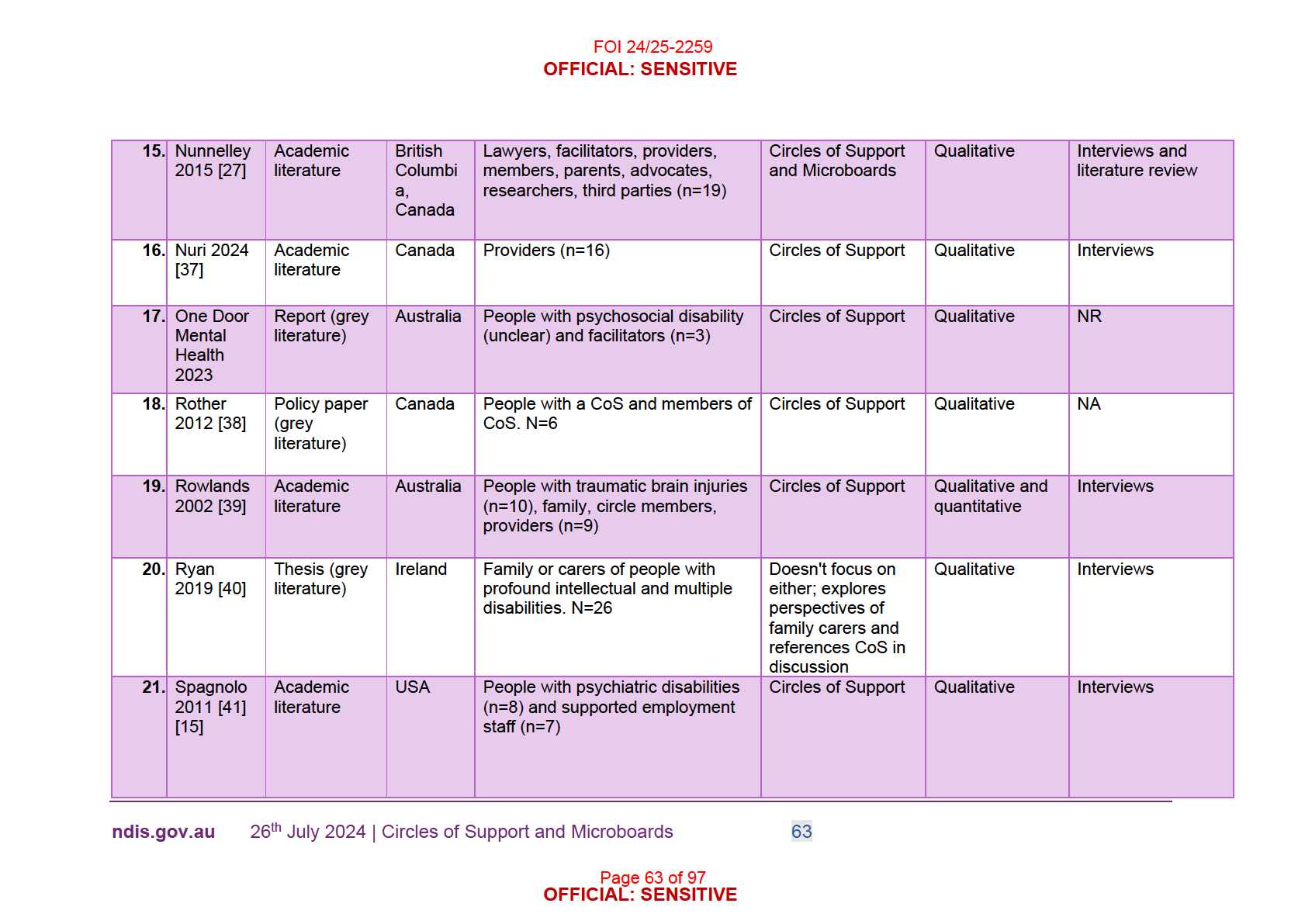

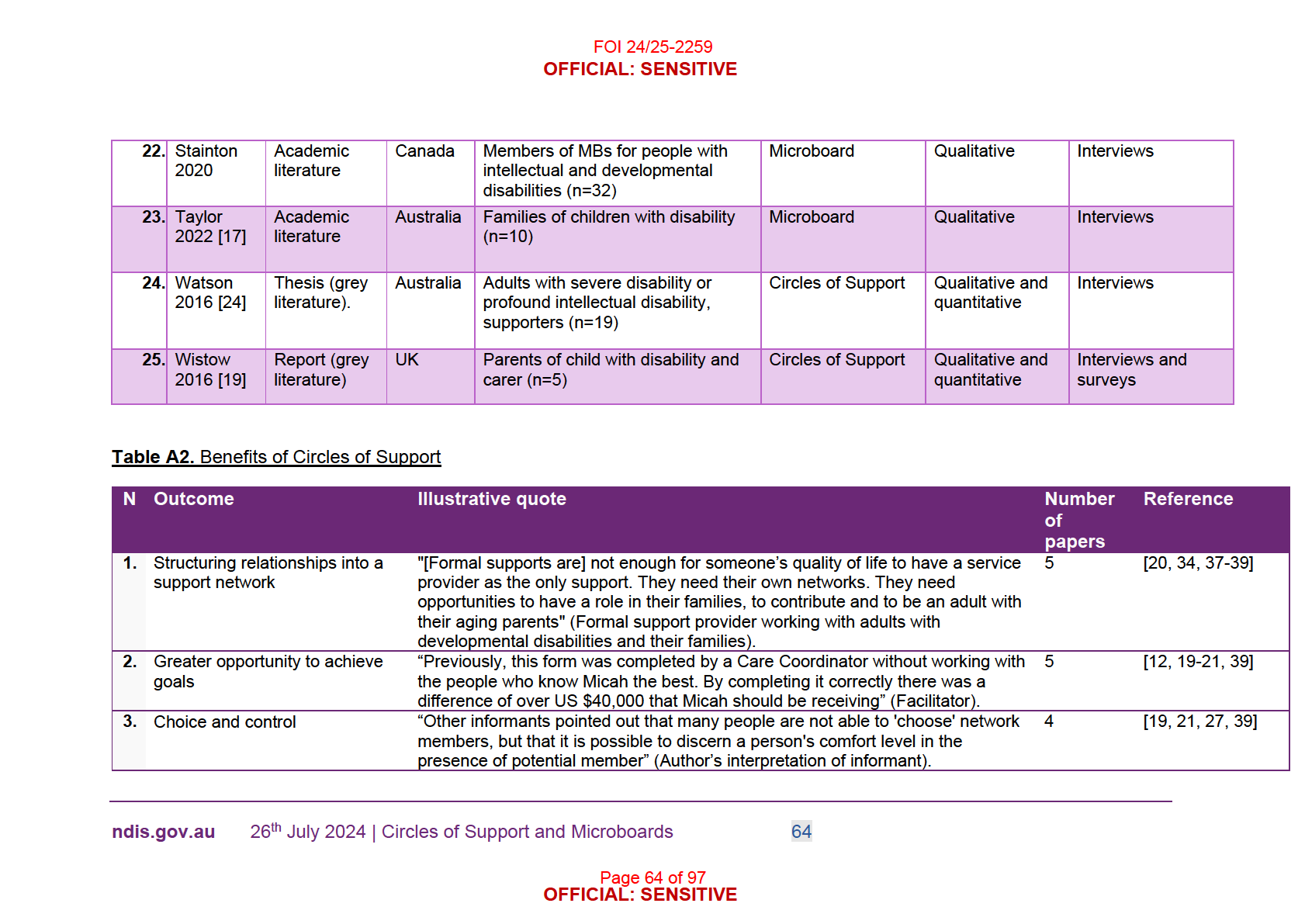

Twenty-seven papers from academic and grey literature reported on the benefits and

risks of setting up and maintaining circles of support and Microboards. Most data

were qualitative, derived from interviews and focus groups with facilitators, carers,

people with disabilities, members of circles of support and Microboards, and service

providers.

A limitation of the data is that authors often summarise interview responses without

providing full quotes. This practice can make it difficult to understand the context or

full meaning of the statements. Additionally, authors may quote other authors'

publications rather than directly quoting interviews, complicating the extraction of

original interview data. This approach lacks transparency and reduces the reliability

of the reported information. To counter this, quotes from PwD (or carers are

highlighted in this chapter. Fortunately, most of the reported benefits are derived

from PwD or their carer’s quotes, so there is a reduced chance of positive bias in our

findings. However, some researchers and their publications are funded by CoSAM

organisations, potentially biasing their results [4, 15-18].

No cost-effectiveness analysis on CoSAM versus usual care was identified in the

literature. One study estimated the cost saving CoS may provide people with severe

learning difficulties by arranging a care package to be delivered in the home and

compared this with the cost of living in fully-staffed residential care (mean £51,000

versus £139,000) [19].

Of the 25 papers, twelve were from Australia (44%), eight from Canada (30%) where

the concept of Microboards originated, three from the UK and Ireland (11%), and

three from the United States (11%). The most reported benefits and risks found in

the literature are shown in bold, and the corresponding references and examples

quotes can be found in “Appendix Table A2-A5”.

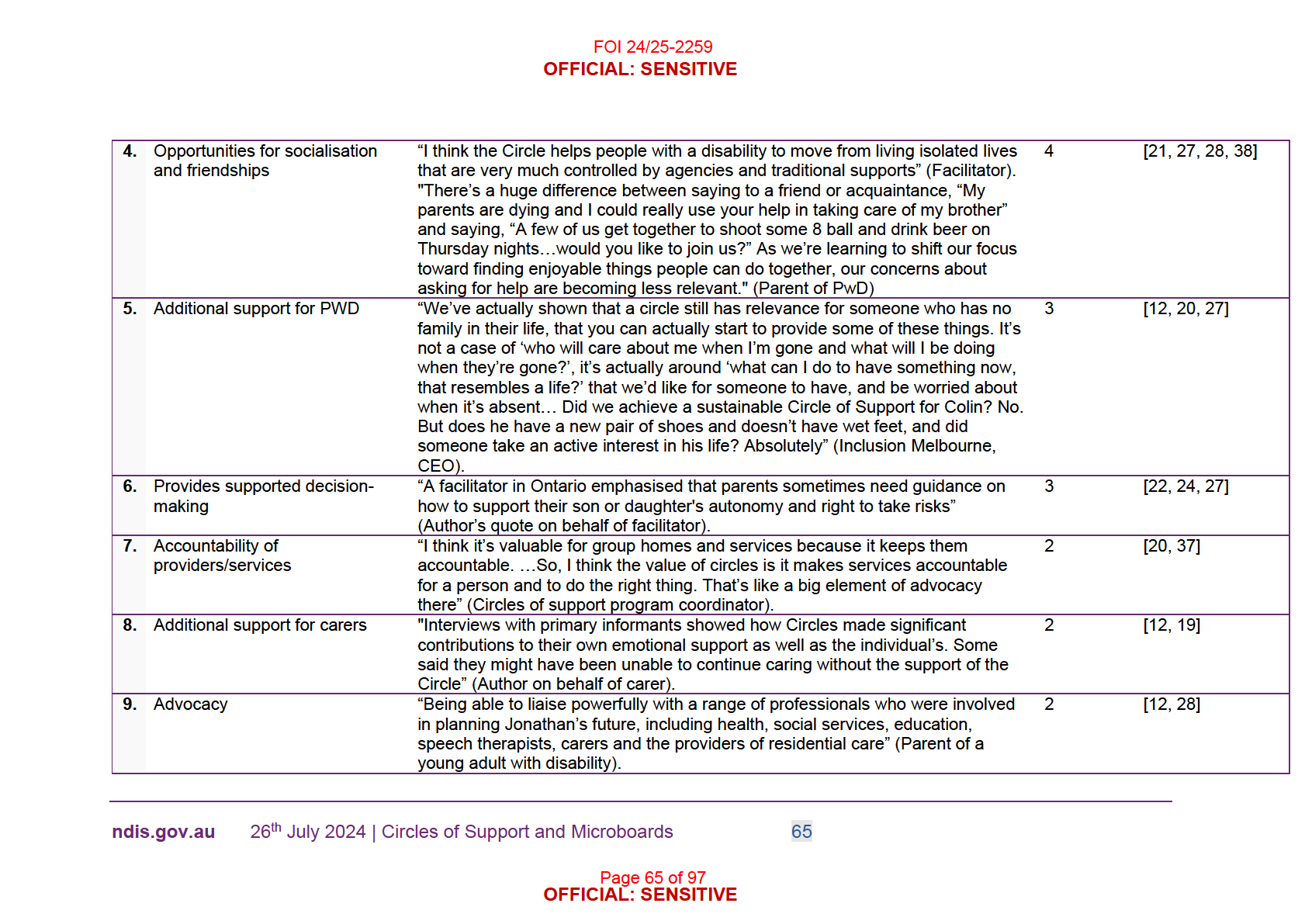

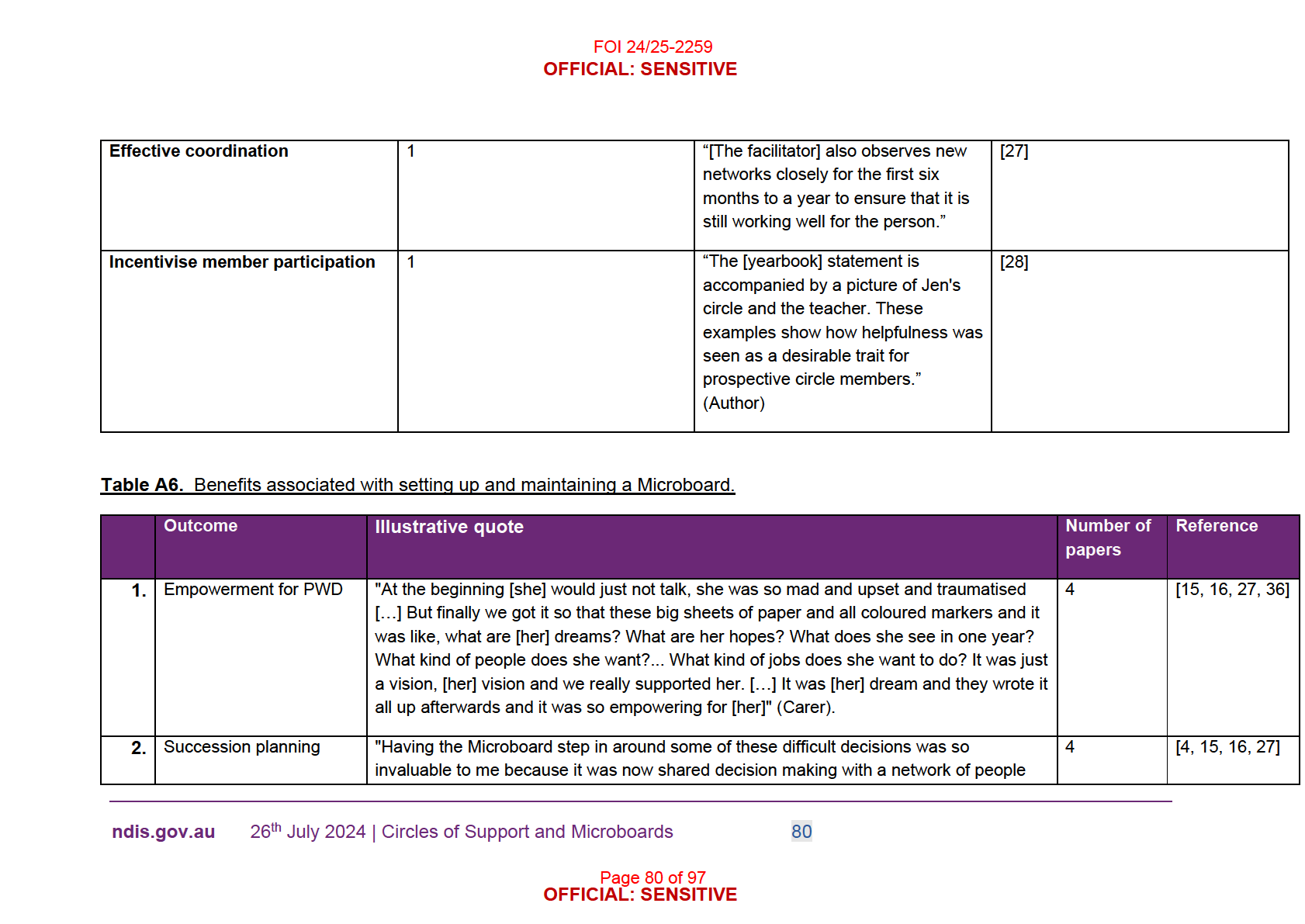

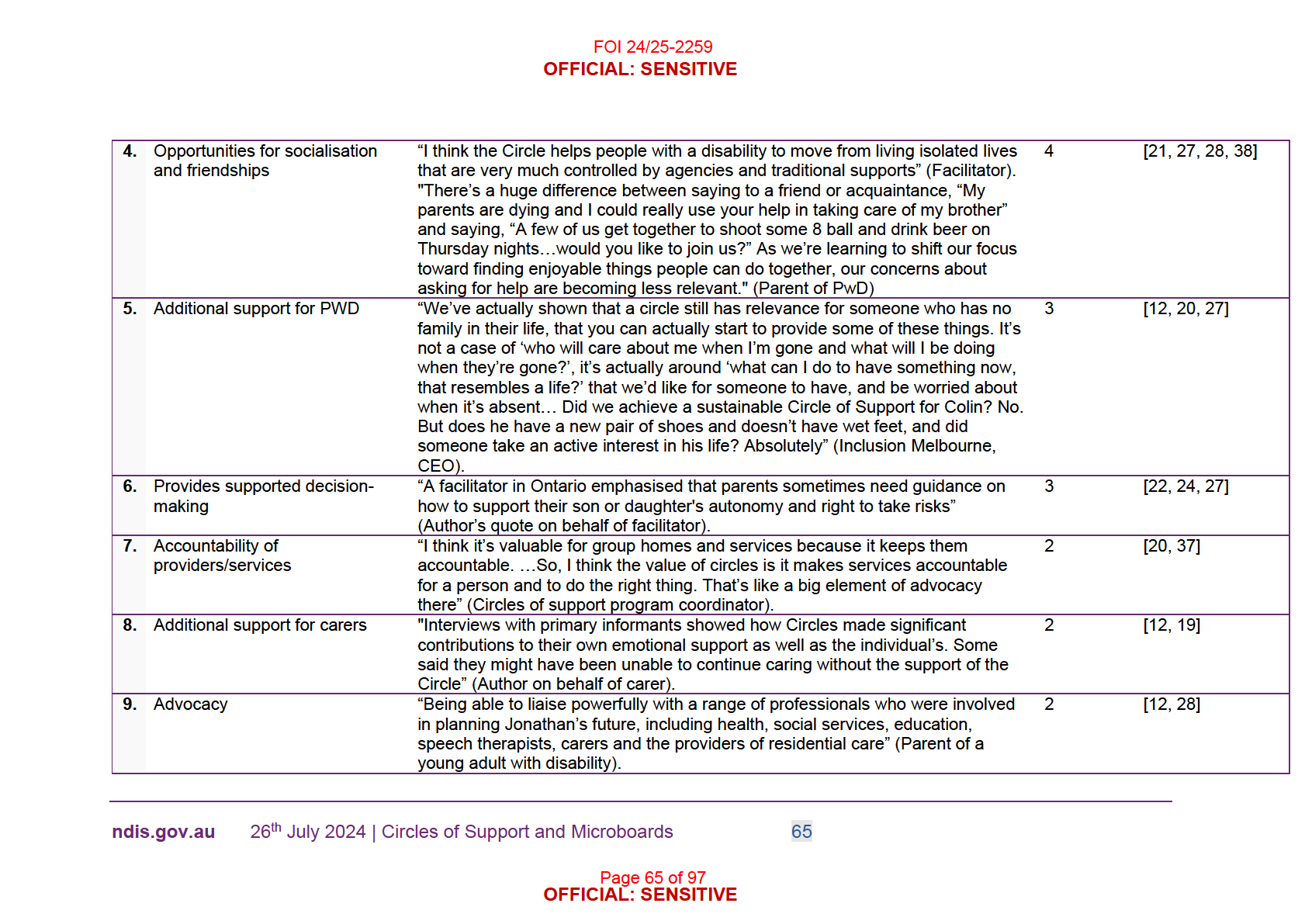

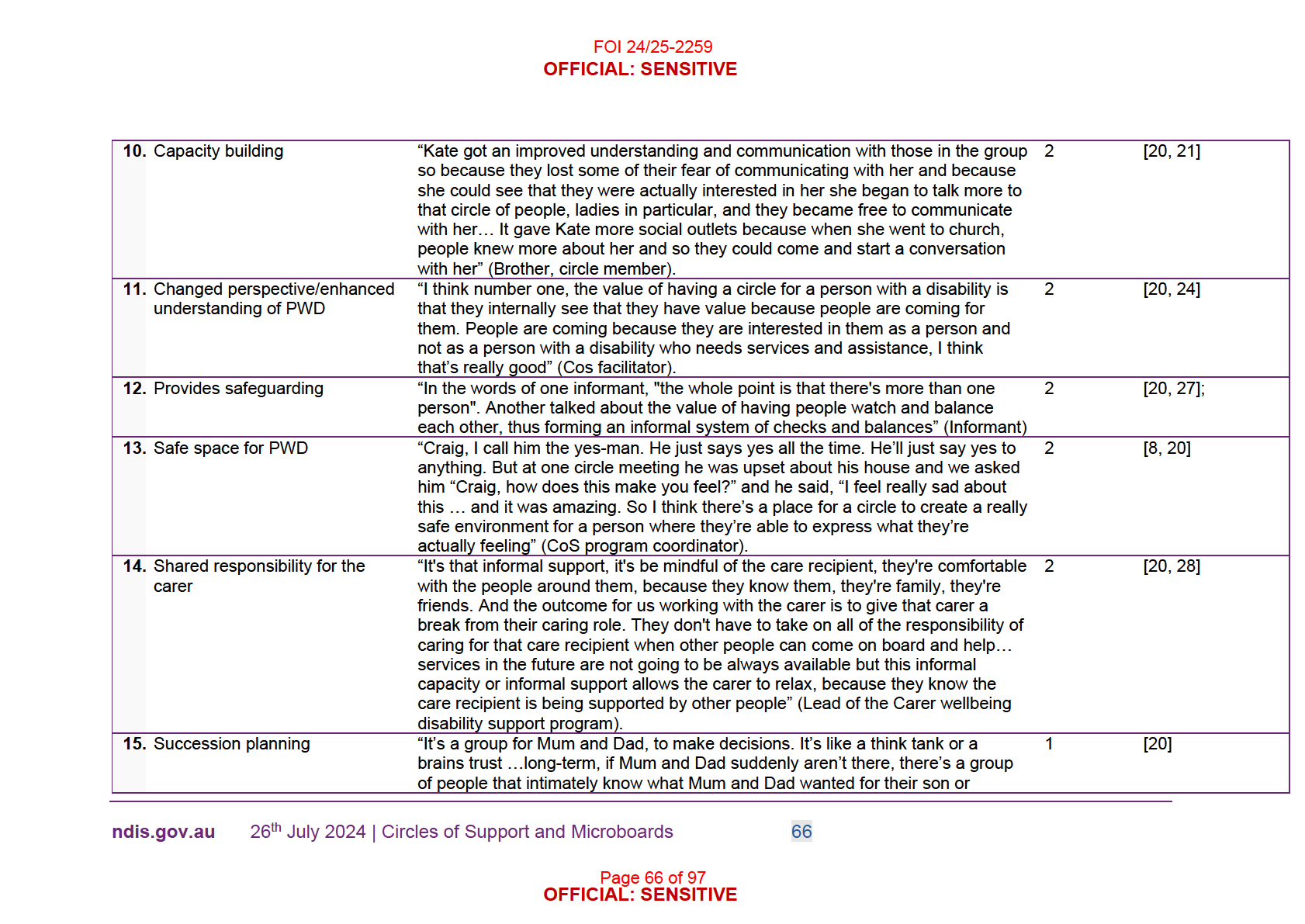

3.1 Benefits of Circles of Support

Supported decision-making.

Structuring existing relationships into a Circle of Support provides numerous

benefits for PwD. It establishes a reliable, coordinated system that regularly meets to

find

greater opportunities for the PwD to achieve their personal and professional

goals. “You know when you get a group of smart people together who've got different

ndis.gov.au

26th July 2024 | Circles of Support and Microboards

33

Page 33 of 97

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

FOI 24/25-2259

OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE

life experience, they are very good at brainstorming…. They clarified issues” (Parent

of PwD) [20].

By providing

supported decision-making, they empower individuals by giving them

choice and control over their lives and the support they receive. A PwD said “good

support like I get has helped me to learn. I go to them and I have people to ask

questions. Other people’s thoughts and ideas help me decide what to do” [21].

Oversight.

Having several members in a Circle of Support increases oversight, ensuring the

PwD receives high-quality services and holding providers to

account. The circle can

also

advocate for the rights and needs of PwD, tasks often left to caregivers who are

frequently exhausted and have limited capacity to challenge the system. They can

also assist those who have minimal support “[CoS can support the] thousands of

people who are living in disability accommodation, who are unable to self-advocate

and do not have family support” (Family of PwD) [22].

Support and respect.

A CoS facilitates

socialisation and friendships, reducing isolation and improving

mental well-being: “Jeff had more people to call on following the program than

before” (Mother, circle member) [22]. Another circle member described “[the circle]

produced major social, psychological and practical outcomes for the individual and

their family” [19]. One member described the Circle’s impact as “massive” for a

person with complex needs who now knew that “people are looking out for her. She

could now take part in activities in the same way as people without disabilities and

was much more integrated in the local community” [19].

It also creates a

safe space for the PwD to feel valued and respected. Engaging

with the CoS fosters a

capacity-building environment, allowing the PwD to

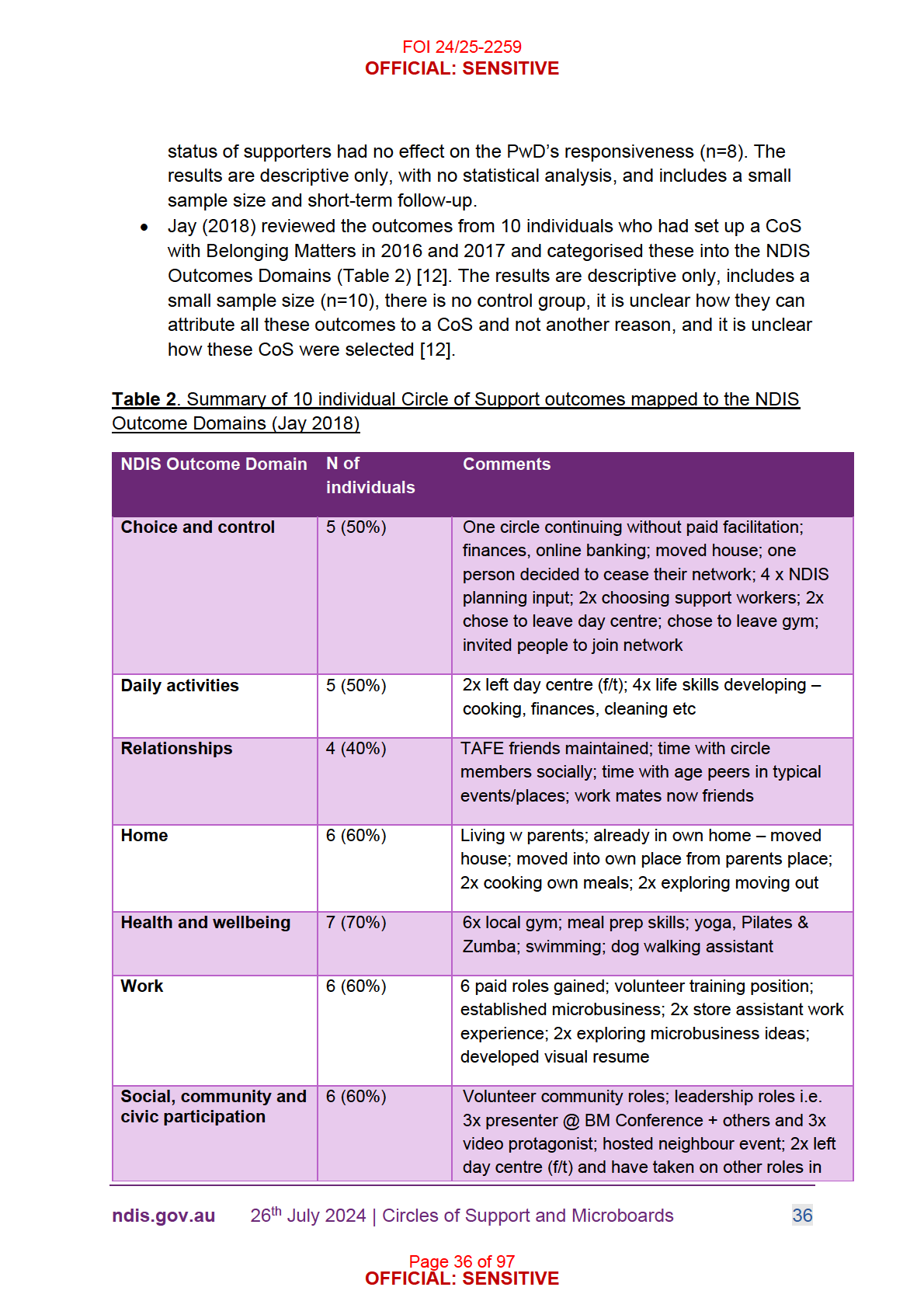

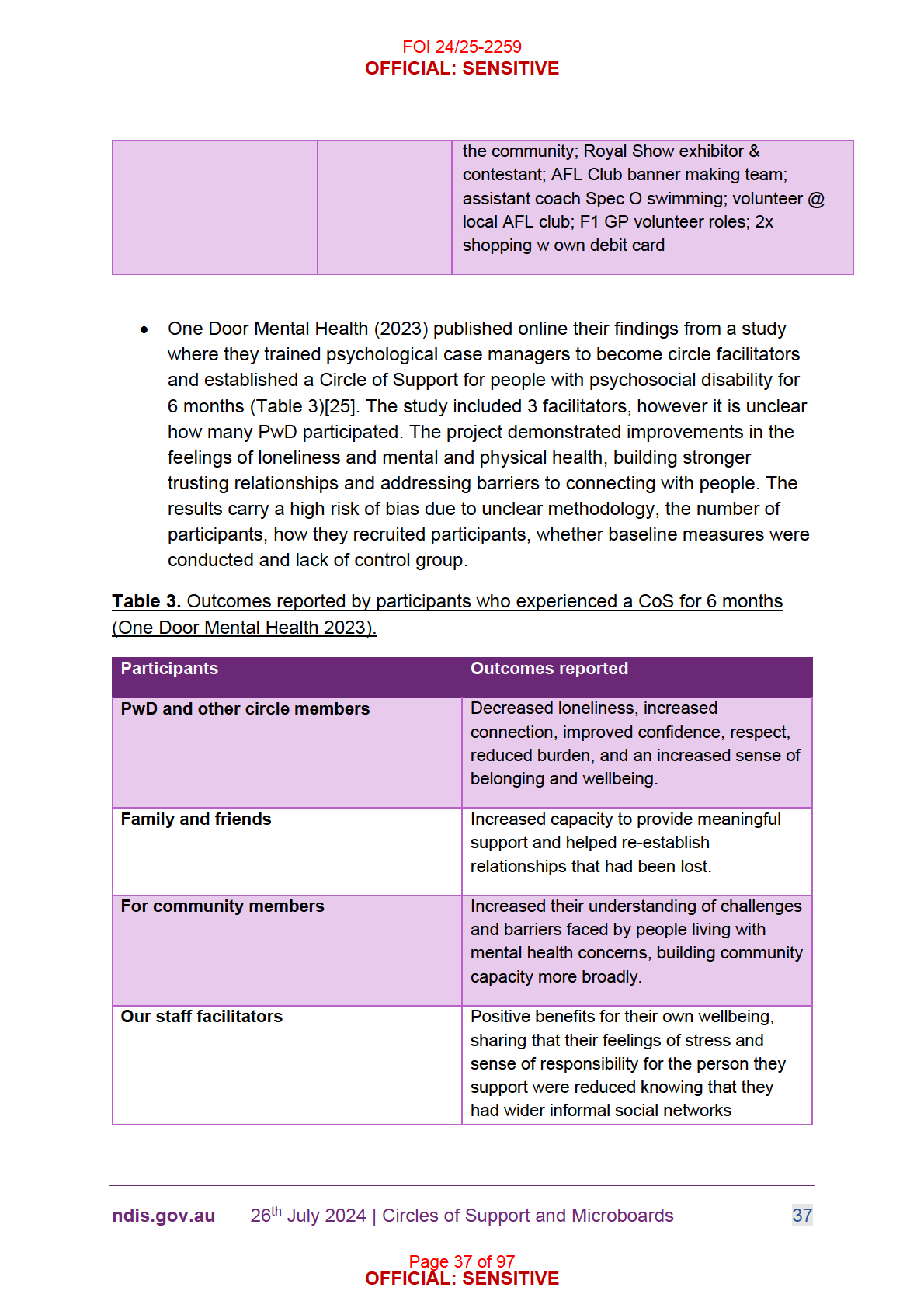

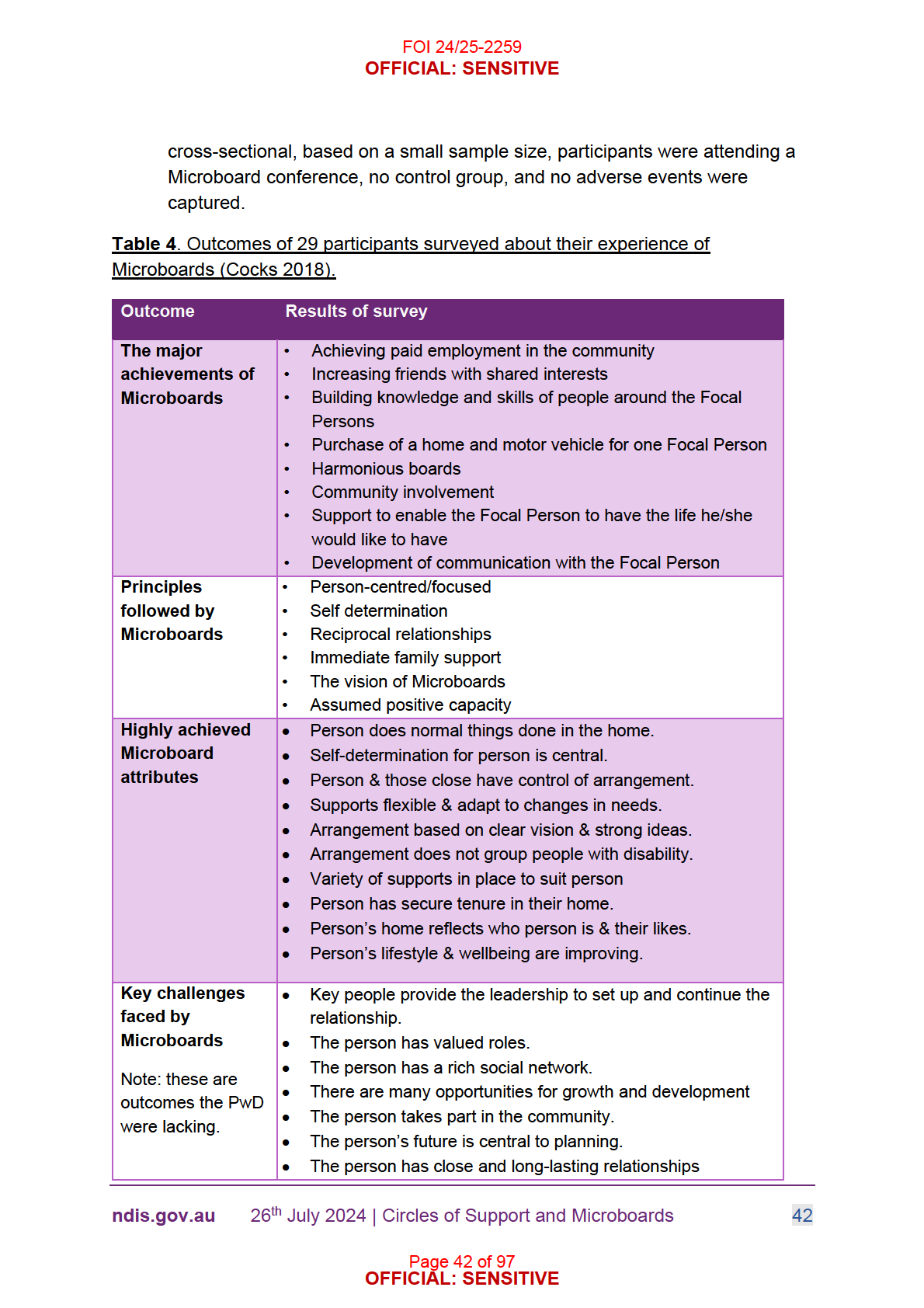

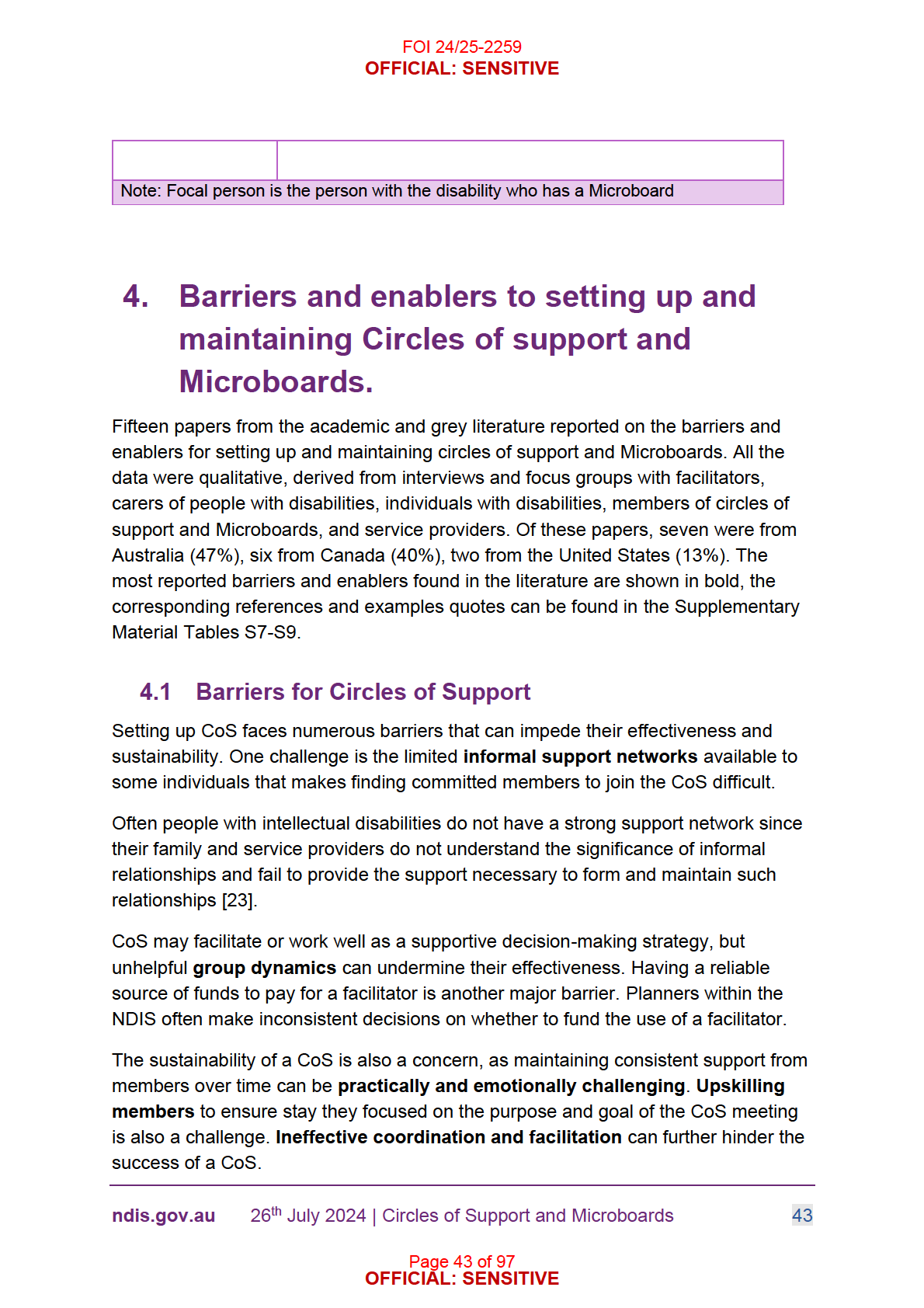

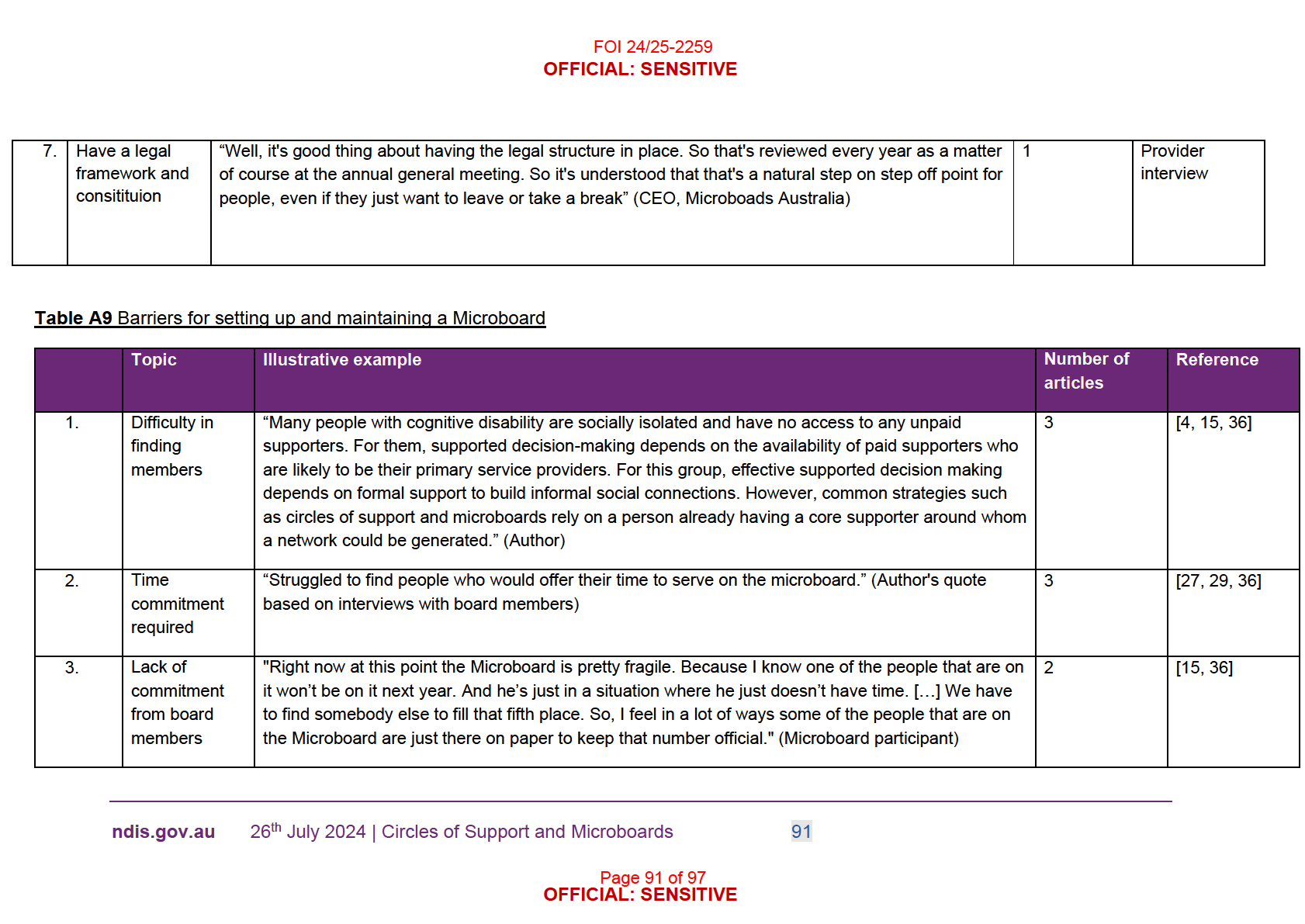

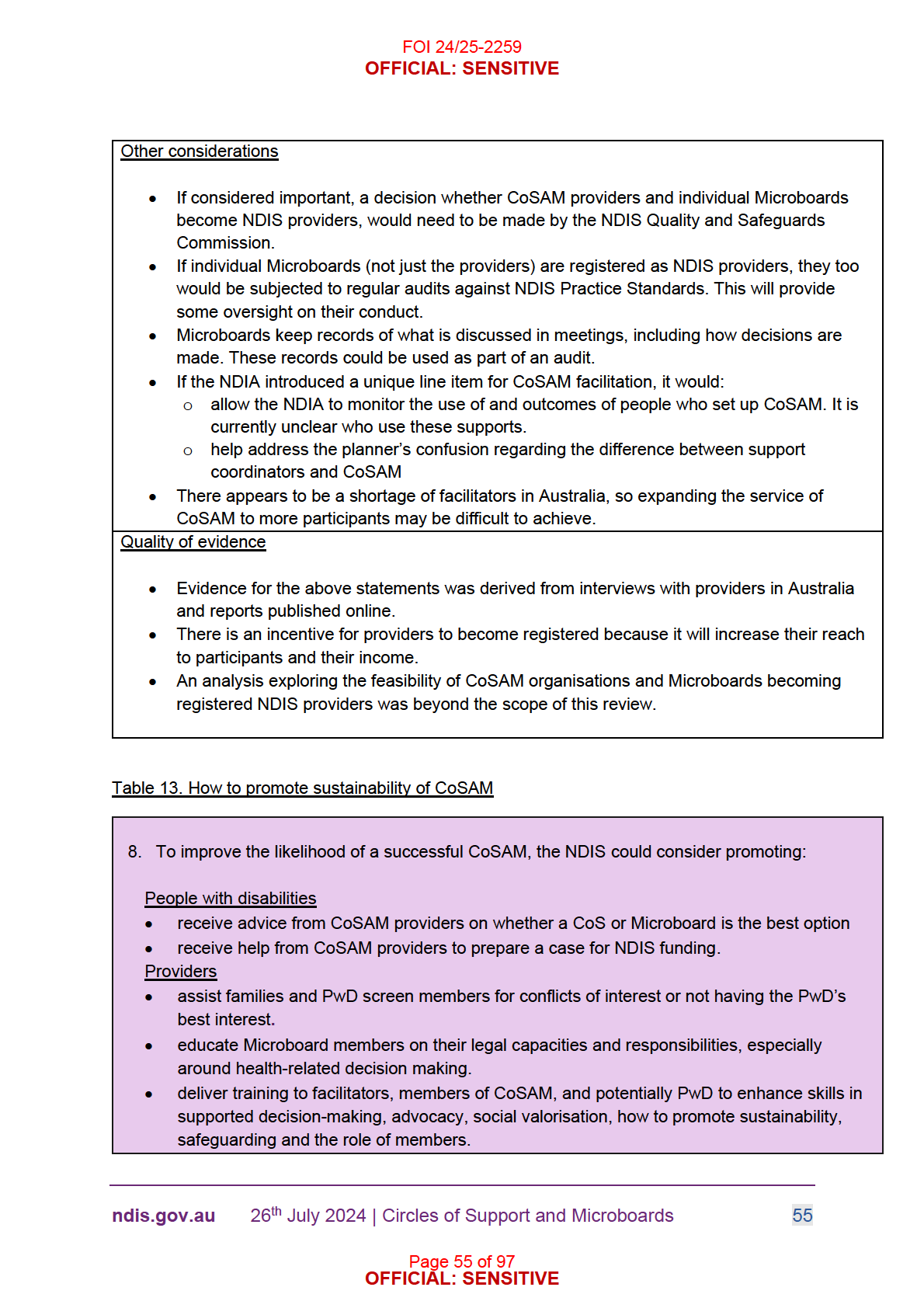

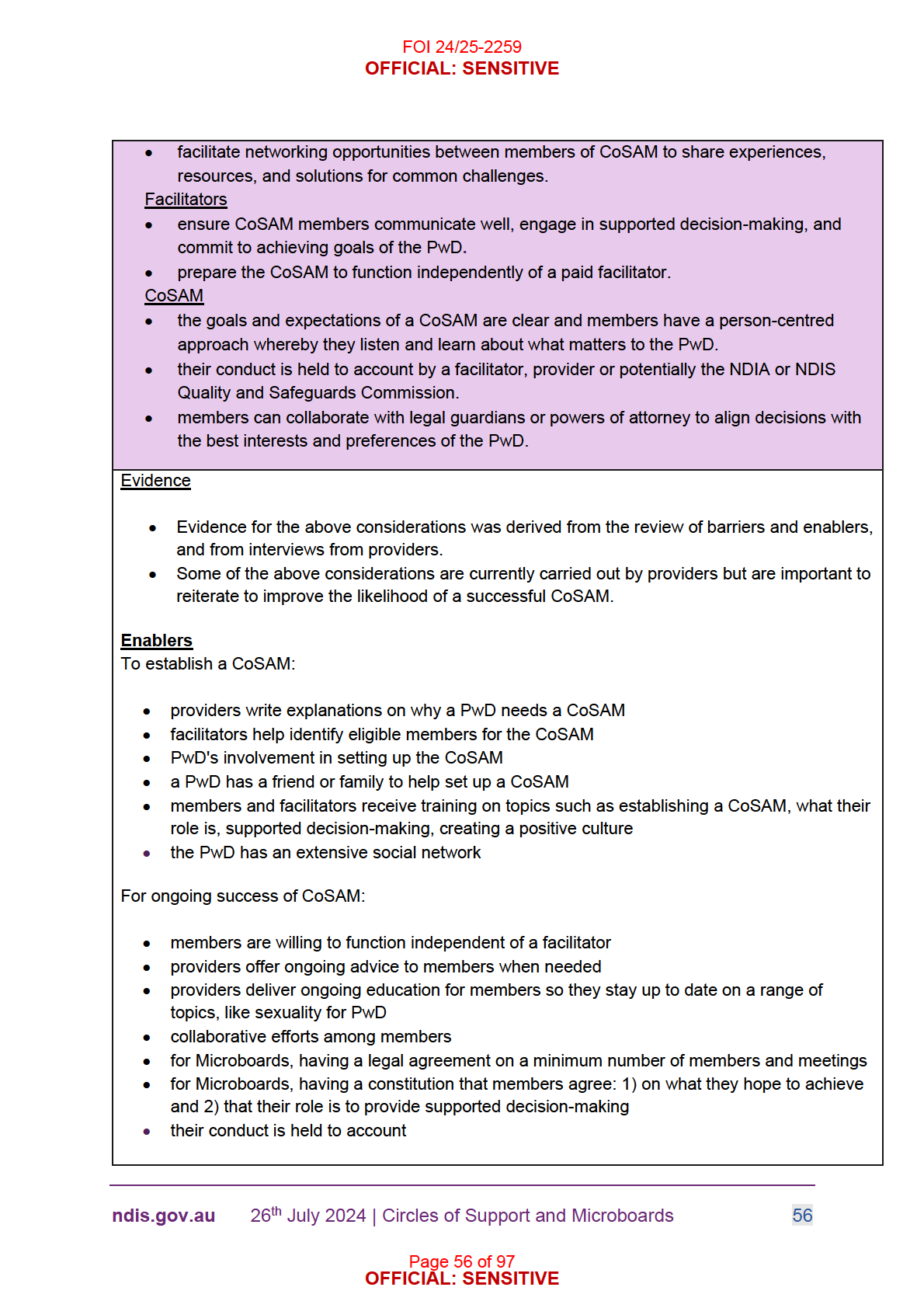

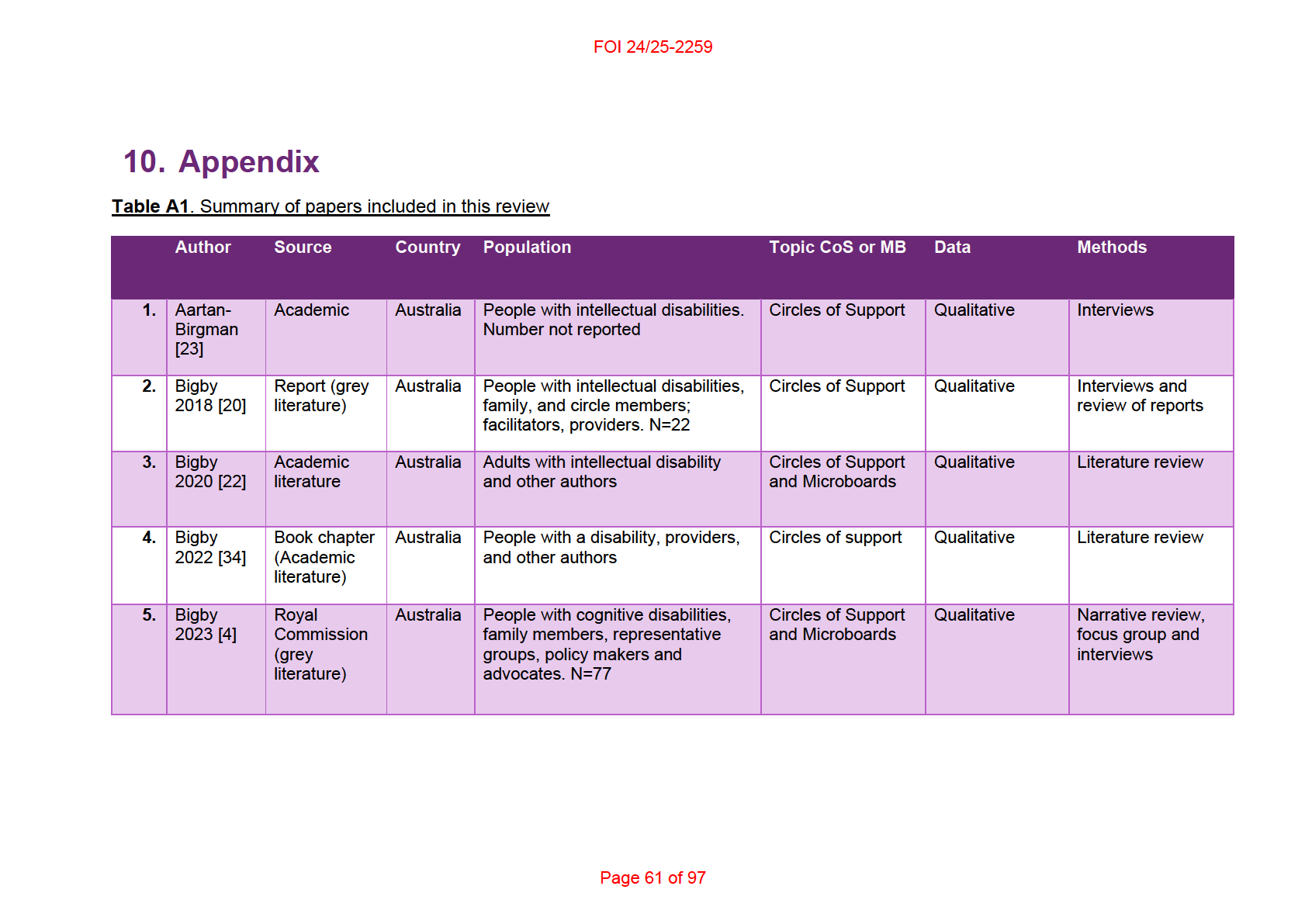

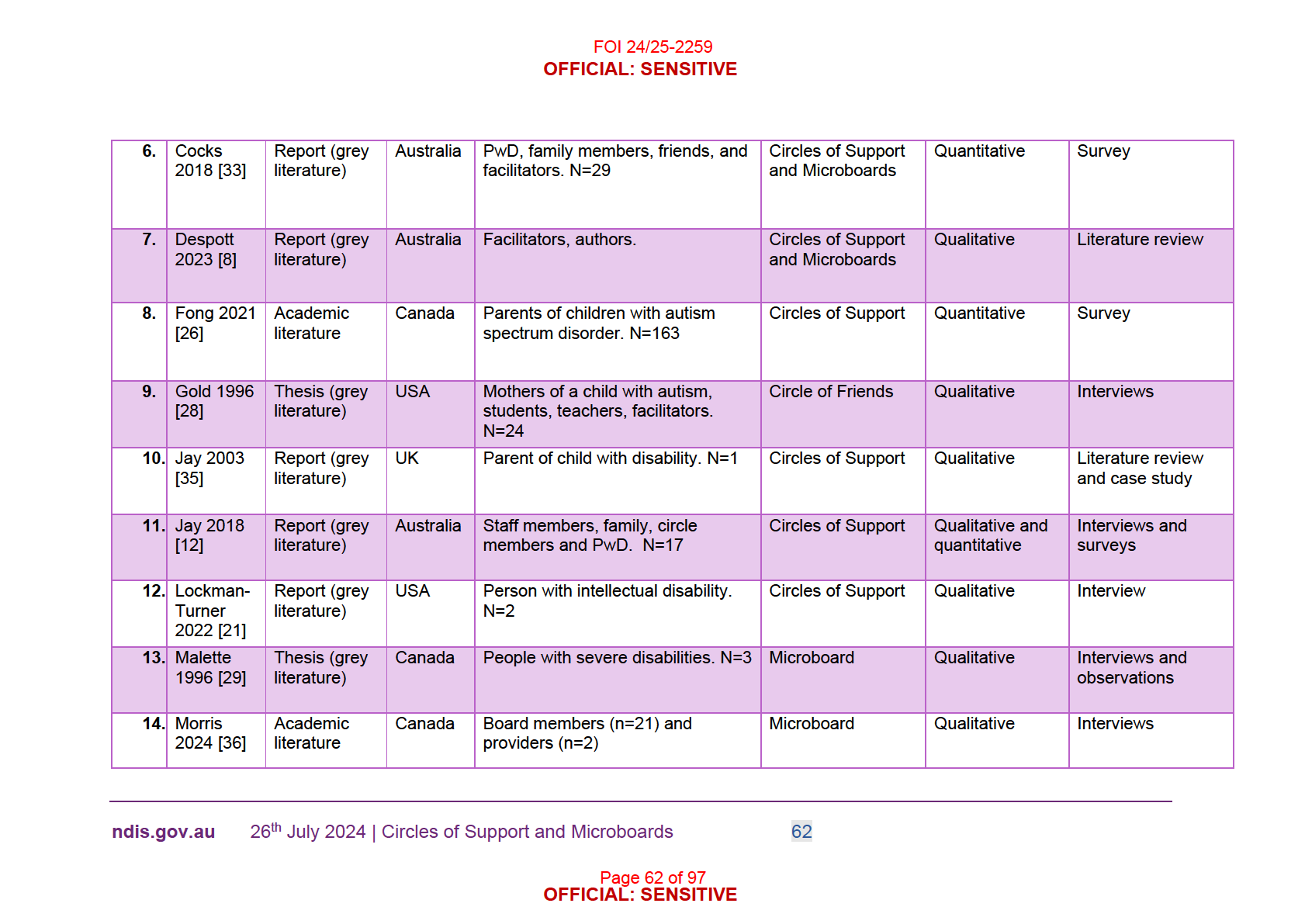

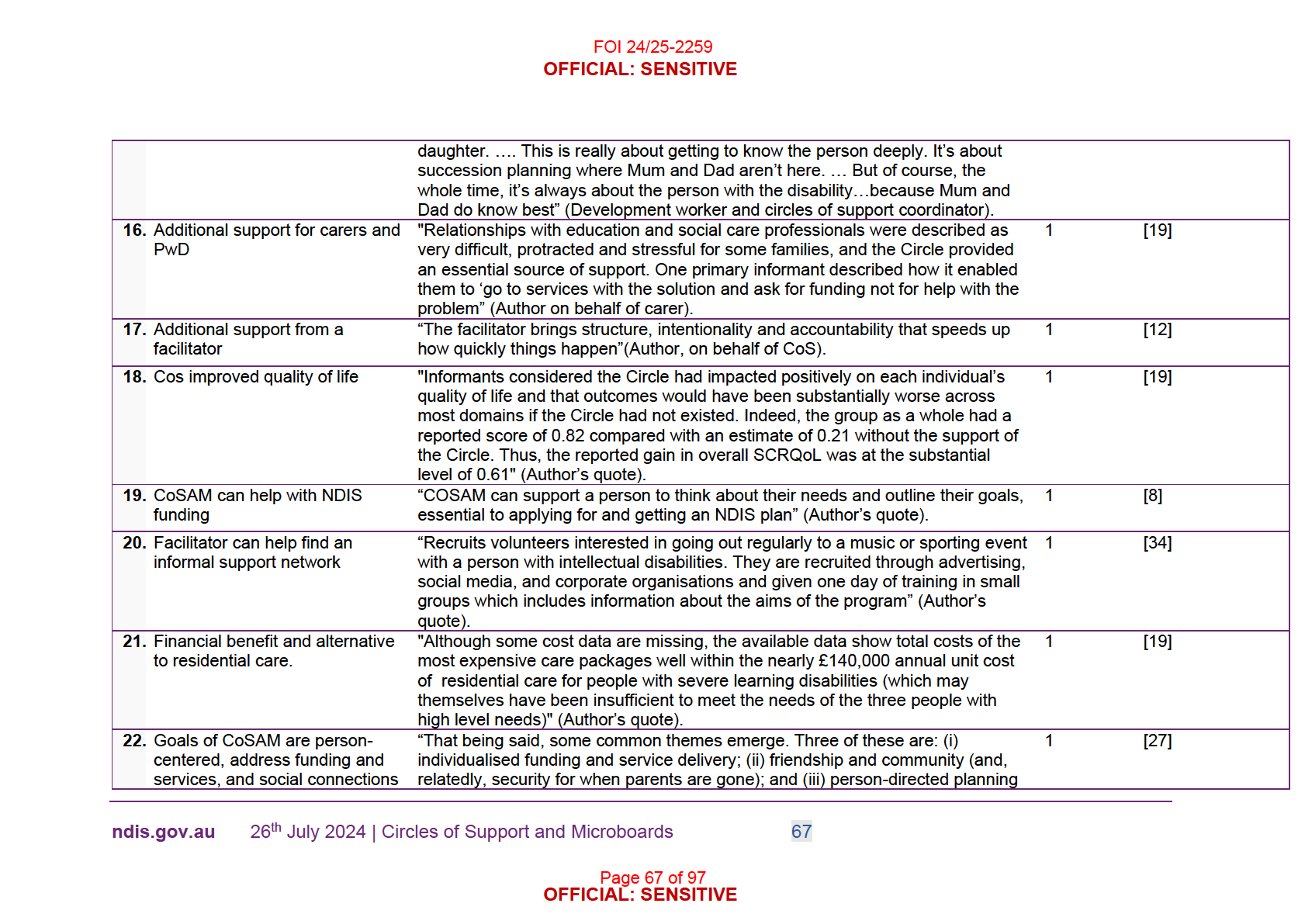

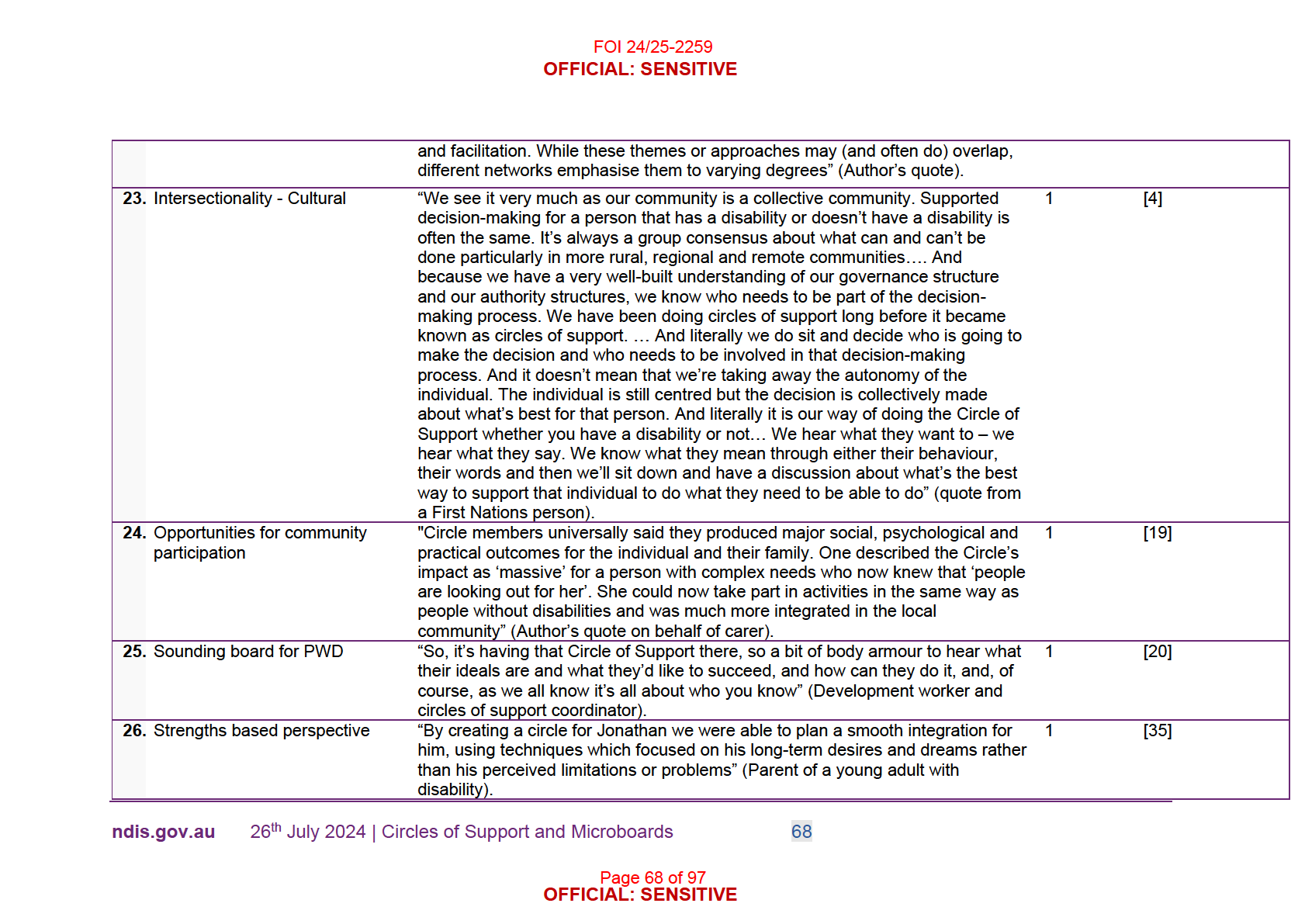

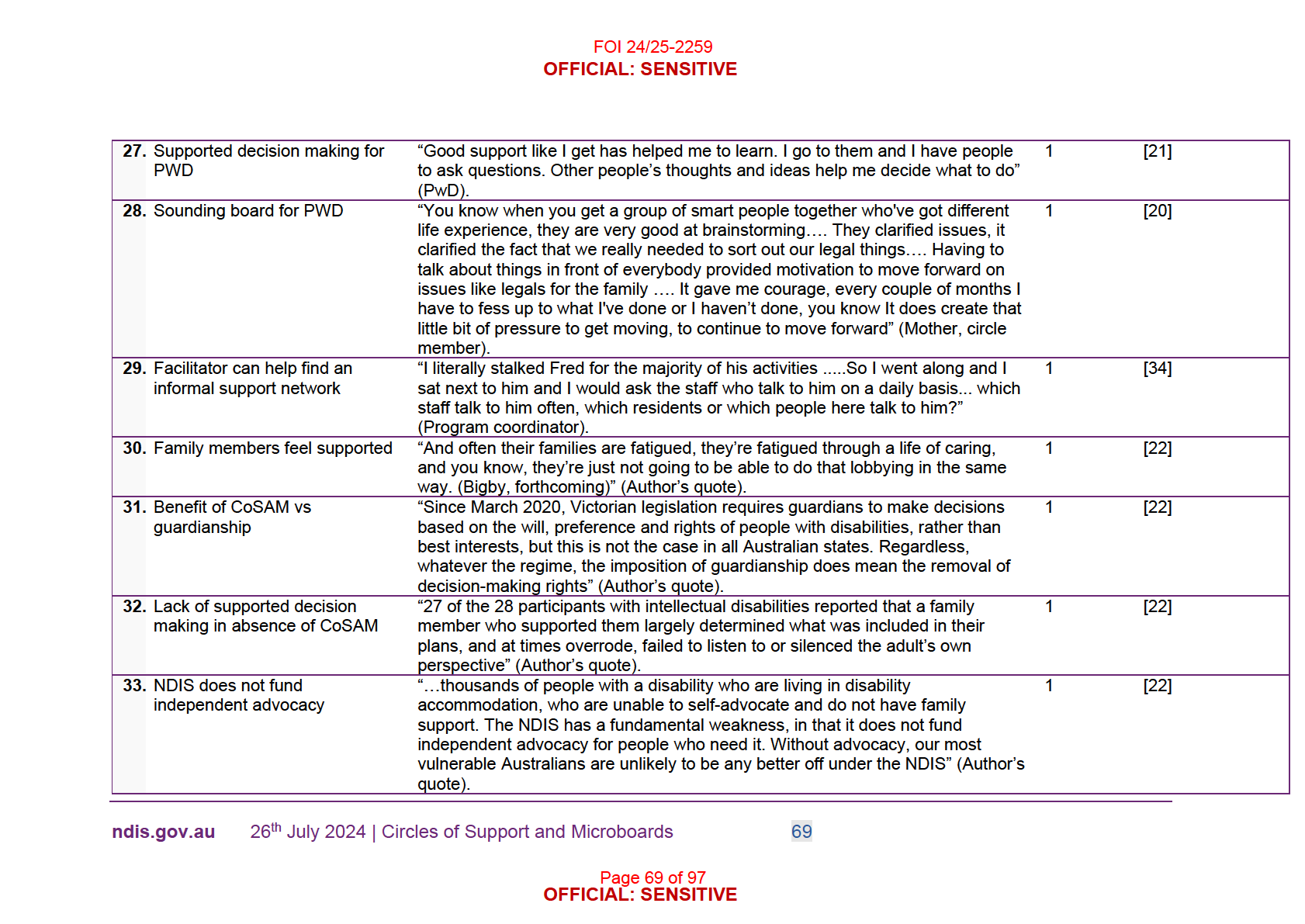

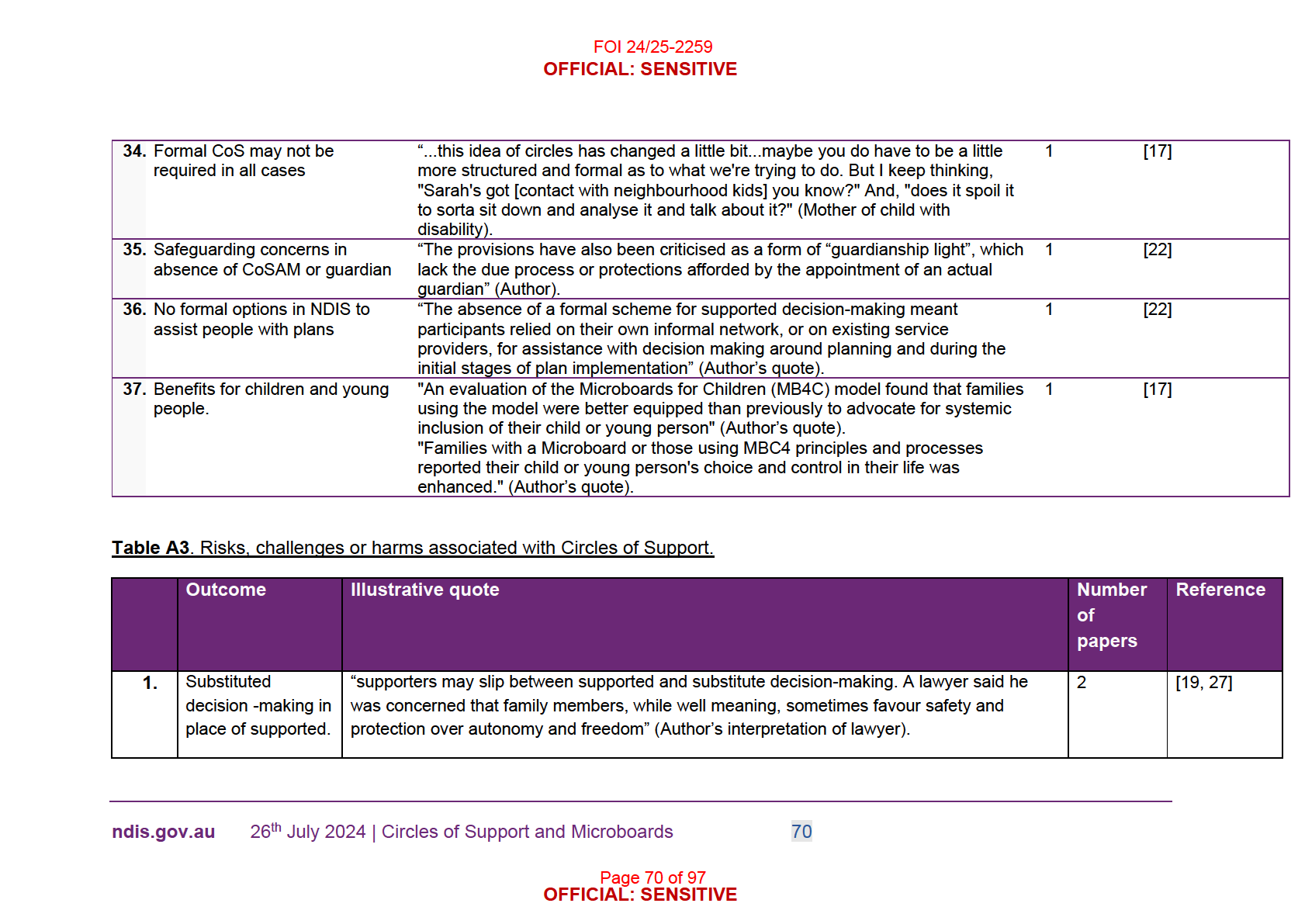

enhance their skills in communication, socialisation, and self-advocacy: “Every